Translated from French with DeepL (please notify us of errors)

I would really like to know if you think that ghosts exist, that they have a form of their own and some kind of supernatural power, or if they lack substance and reality and only take shape out of our fears.»[1].

This question plagued Pliny the Younger, one of the most erudite minds of his time. His uncle and adoptive father was the author of a monumental encyclopaedia. He died because he wanted to study too closely the eruption of Vesuvius that destroyed Pompeii in October 79. The young Pliny, aged about seventeen, witnessed the catastrophe from afar, which he later described so accurately in a letter to Tacitus that volcanologists are still grateful to him. But for the time being, what preoccupies him are the spectres.

«If, as usual, you weigh the pros and cons, yet let the scales tilt to one side to bring me out of the perplexity in which I am, for I consult you only to deliver me from it.»[2]

So who can Pliny the Younger count on to decide the question? Another illustrious man, about twenty years older than him: Lucius Licinius Sura. He was born in Tarraco, now Tarragona in Spain. He was a homo novus –today we would say a self-made man– who became a wealthy senator, friend and adviser to the emperor Trajan, and protector of the poet Martial.

Pliny gives three ghost stories to Sura for his consideration.

The first concerns a certain Marcus Rufius. «At the end of the day, he was walking under a portico, when a woman of superhuman size and beauty appeared before him. Fear seized him: ‘I am Africa,’ she said; ‘I have come to foretell your destiny»[3]. The apparition foretold Lucius that he would hold great offices in Rome, return to govern the province of Africa, and die there. Pliny considers the prediction to have been fulfilled, but the character has left few traces. It is therefore difficult to form an opinion. Moreover, the apparition is not really a ghost, but the incarnation of a mysterious region for the Romans. Anyway, let’s move on to the second case.

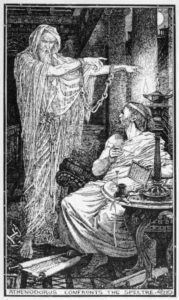

The story takes place in Athens and has as its protagonist the Stoic philosopher Athenodorus of Tarsus. It takes place a good century before Pliny’s account. There was a large and beautiful house in the city. But as soon as night fell, the sound of chains was heard, followed by the appearance of a hideous spectre, in the shape of a shaggy old man. The successive occupants had all fallen ill in terror or fled. The estate agents of the time, however, did not give up. The house was advertised as being for sale at a very low price. The philosopher jumped at the chance.

«Towards evening, he had a bed made up in the entrance hall, asked for his tablets, his stiletto and some light. (…) At first a deep silence, the silence of the night, soon a rustling of iron, the sound of chains. He, without looking up, without leaving his tablets, summons his courage to reassure his ears. The clatter increases, comes closer, is heard near the door, and finally in the room itself. The philosopher turns around. He sees, he recognizes the ghost as he has been described. The spectre was standing, and seemed to be calling him with its finger. Athenodorus beckoned him to wait a moment, and began to write again.»[4]

That is what being stoic is all about. As the ghost insists, the philosopher finally follows him into the garden. There, at the place indicated by the ghost, bones and chains are discovered while digging. Athenodorus has these remains buried in public: the problem is solved, the house is no longer haunted.

Well, Pliny wrote to his interlocutor, these stories are second-hand. The third one is real. He follows up (so to speak) with the story of one of his freedmen, Marcus, «who is not uneducated», he says. So he’s not the first gullible person to come along and this is what happened to him:

«As he lay in bed with his younger brother, he thought he saw someone sitting on his bed taking scissors to his head and cutting his hair above his forehead. At daybreak he was found to have the top of his head shaved off, and his hair was found scattered around him.»[5]

A few days later, the spectre that shaves gratis strikes again. Pliny believes that there was no follow-up to these events, but that it may have been to warn him of an averted danger, as it was the custom of the accused to let their hair grow. It seems that the emperor Domitian had Pliny in his sights, but did not live long enough to threaten him…

These are the elements provided in the file to determine this. Three stories of rather harmless and benevolent spectres taking place over more than a century: we agree that this is a bit thin!

As for Sura’s answer, it has not reached us and we will never know it…. unless her ghost reveals it to us.

Source

Letters of Pliny the Younger Book VII, XXVII. Pliny to Sura. Text in English and Latin.

[1] Igitur perquam velim scire, esse phantasmata et habere propriam figuram numenque aliquod putes an inania et vana ex metu nostro imaginem accipere.

[2] Licet etiam utramque in partem — ut soles — disputes, ex altera tamen fortius, ne me suspensum incertumque dimittas, cum mihi consulendi causa fuerit, ut dubitare desinerem.

[3] Inclinato die spatiabatur in porticu; offertur ei mulieris figura humana grandior pulchriorque. Perterrito Africam se futurorum praenuntiam dixit.

[4] Ubi coepit advesperascere, iubet sterni sibi in prima domus parte, poscit pugillares stilum lumen (…) Initio, quale ubique, silentium noctis; dein concuti ferrum, vincula moveri. Ille non tollere oculos, non remittere stilum, sed offirmare animum auribusque praetendere. Tum crebrescere fragor, adventare et iam ut in limine, iam ut intra limen audiri. Respicit, videt agnoscitque narratam sibi effigiem. Stabat innuebatque digito similis vocanti. Hic contra ut paulum exspectaret manu significat rursusque ceris et stilo incumbit.

[5] Est libertus mihi non illitteratus. Cum hoc minor frater eodem lecto quiescebat. Is visus est sibi cernere quendam in toro residentem, admoventemque capiti suo cultros, atque etiam ex ipso vertice amputantem capillos.

Other articles in English from the Nunc est bibendum blog