Translated from French with DeepL (please notify us of errors)

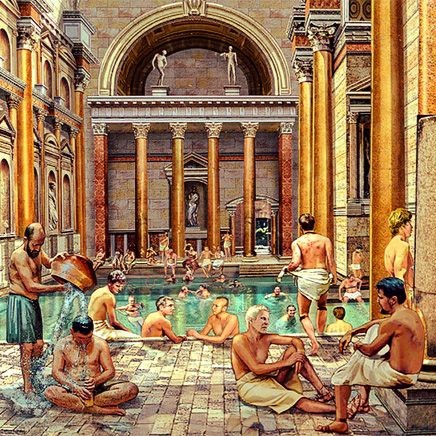

The houses and streets witness a joyous outburst: the crowd goes out to form festive processions, the servants are served by their master, they can criticize the authority without fear. Work and all public activity cease. In the houses, which are decorated with holly, mistletoe and ivy garlands, parties and banquets are organised. Gifts are exchanged -jewellery, figurines, good luck charms and sweets. Children are particularly pampered and even receive small amounts of money. People also gather to eat a cake in which a bean is hidden. Whoever falls on it is designated “King of the banquet” and can give pledges to the other guests…

Christmas? Epiphany? Carnival?

No, but the Roman festival of Saturnalia, which preceded and inspired them.

Saturnalia takes place on 17 December in the few days before the winter solstice. The duration of the festivities has varied over time: in the 1st century BC, in the time of Cicero, it was one week. Then, after Saturnalia, there was the celebration of the Sigillaria, small terracotta figurines that were sold, offered and exhibited. Santons before their time.

With these end-of-year celebrations, people prepared for the longest night of the year, but they also celebrated the return of the lengthening days and thus, symbolically, the victory of light over darkness, the first fruits of the future harvest.

In a text that takes the festival of Saturnalia as its setting, the fourth-century author Macrobius has his characters discuss the origins of the festival, which is said to date back to well before the founding of Rome.

He tells us that Janus, the two-faced god who reigned in Latium at the time, had welcomed Saturn, who had been driven out of the sky by Jupiter. Janus had learned from his host the art of agriculture and the art of preparing food. Janus and Saturn reigned together in a peaceful and happy golden age where slavery did not exist and no theft was committed.

Originally, Saturn was seen as a god of sowing, sometimes represented with a sickle. His name comes from the Latin word sator, the sower.

Then Saturn disappeared and Janus established the Saturnalia to honour him.

“Janus was also the first to mint coins”,

says Macrobius,

“and in this he also marked his deference to Saturn: as the latter had arrived in a boat, he had his head represented on one side, and on the other a ship, in order to transmit his memory to posterity.”[1]

As proof of the veracity of this story, which Ovid had already told some 400 years earlier[2], Macrobius points out that in his time, people still played heads or tails by saying capita aut navia, “heads or ships”, according to the figures that adorned the sides of certain coins…

On December 17, therefore, the crowds of Rome flocked to the temple of Saturn in the Forum at the foot of the eastern slope of the Capitol. The statue of the god was stripped of the woollen chains that bound it for the rest of the year. A priest, with his head uncovered, proceeded to make a sacrifice. The crowd shouted:

IO SATURNALIA!

During this festival, in memory of the golden age of Janus and Saturn, the authority of masters over slaves was suspended, the social order reversed in a parodic and temporary way. Slaves had the right to speak and act, were free to criticise their masters’ shortcomings and could even be served by them. Courts and schools were closed. The work of the humble stopped for a few days.

This no doubt explains the immense popularity of Saturnalia at the time… and the fact that certain features of the festival have been perpetuated to this day.

[1] Macrobius, Saturnalia, I, VII, 22 : Cum primus quoque aera signaret, servavit et in hoc Saturni reverentiam, ut, quoniam ille navi fuerat advectus, ex una quidem parte sui capitis effigies, ex altera vero navis exprimeretur, quo Saturni memoriam in posteros propagaret. Aes ita fuisse signatum hodieque intellegitur in aleae lusum, cum pueri denarios in sublime iactantes capita aut navia lusu teste vetustatis exclamant.

[2] Ovid, The Fastes, I.

Other articles in English from the Nunc est bibendum blog