Translated from french with Deepl (please notify us of errors)

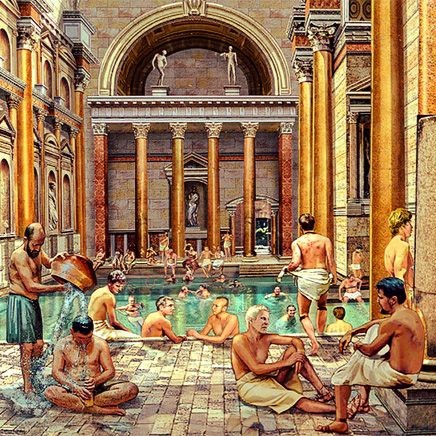

We have our ‘Rock Paper Scissors’, the Romans had their digitis micare[1], literally ‘waving your fingers around’. The principle is very simple: two people face each other, fist clenched. At the same time, they extend a certain number of fingers while shouting out a number between zero and ten[2]. Whoever guesses the number of fingers held out by the two protagonists wins. Of course, the rules vary according to time and place.

Chance is the name of the game, but not the only one. The game requires speed, presence of mind and a sense of strategy. Depending on what you know about the other player’s psychology and what they played in the previous round, you can try to guess the number of fingers that will appear. In the same way, you can try to outwit your opponent’s prediction.

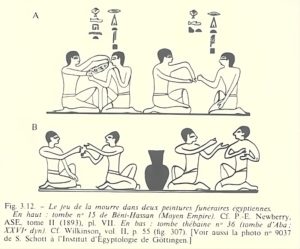

The origins of the game are lost in the mists of time. It appears to have been represented in several Egyptian tombs as far back as the Middle Kingdom (around 4,000 years ago). Traces of it can also be found in the ancient Greek world, although the game does not seem to have been very important there. The situation was quite different in Roman times, where micare was commonplace.

It was a recreational game, but also a means of drawing lots.

Double or nothing

Cicero gives an example of how this is used in his Treatise on Duties (De officiis). Let’s take the case of two shipwrecked men struggling to survive in the water. If there is only one plank to hold on to, which one should give it up to the other? The one whose life matters most to himself or to the Republic,’ replies Cicero. Yes, but what if there is a tie? ‘Then there will be no struggle, but, as if it were a drawing of lots or a game of micare, the loser will give way to the other’.[3]

In his work on divination, Cicero elaborates on what he means by casting lots:

“What, then, is consulting fate? It is more or less the same thing as playing dice or jacks, i.e. games in which it is not reason or considered calculation that leads to victory, but reckless daring, well served by chance”.[4]

As we have seen, the stakes could be considerable. Suetonius gives an example. To illustrate the cruelty of the emperor Augustus, he recounts that:

” (…) a father and a son begging him to grant them their lives, he [Augustus] ordered that they play micare [which would have their lives saved] or that they fight together, promising mercy to the victor”.[5]

When so much is at stake in the draw, players may be tempted to cheat. That’s why the game also relies on mutual trust between the protagonists, to the point of becoming the proverbial symbol, notably in Cicero and Petronius:

“(…) But correct, solid, a friend to his friends; we would have played micare with him in the dark”.[6]

To be able to play blindly in the certainty that your opponent will not cheat – that is the height of confidence!

The Roman practice of micare spread and was perpetuated over the centuries, under the name of game of morra, from southern Italy to the Franco-Provençal and Occitan regions. The game was frequently banned, as it involved betting money and provoked fights. It was banned in France in 1931, until it was reintroduced in 2022. And in 2023, the morra even achieved consecration with a UNESCO world heritage listing. What a reversal of fortune!

[1] The noun micatio, which also designates the game, appears to be a late addition and is not used by Latin authors, who generally use the verb micare without the complement digitis.

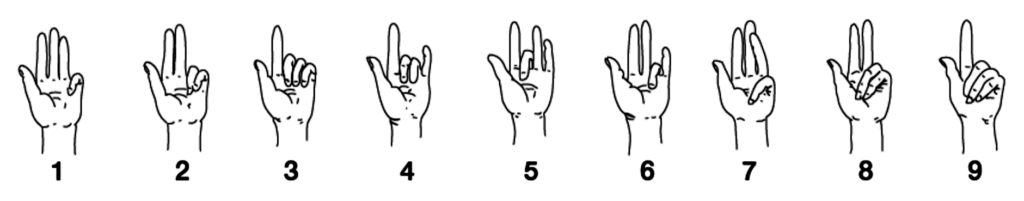

[2] The Romans had a particular way of representing numbers with their fingers. This is the subject of the article Un ‘computer’ au bout des doigts.

[3] Cicero, De officiis, III, 23 (90): Nullum erit certamen, sed quasi sorte aut micando victus alteri cedet alter.

[4] Cicero, De divinatione, II, 41: (…) Quid enim sors est? Idem prope modum quod micare, quod talos iacere, quod tesseras, quibus in rebus temeritas et casus, non ratio nec consilium valet.

[5] Suetonius, De vita duodecim Caesarum, Augustus, XIII, 2, 13: (…) patrem et filium, pro uita rogantis sortiri uel micare iussisse, ut alterutri concederetur, ac spectasse utrumque morientem, cum patre, quia se optulerat (…).

[6] Petronius, Satiricon, 44 (XLIV): (…) Sed rectus, sed certus, amicus amico, cum quo audacter posses in tenebris micare.

Cicero, De Officis, III, 19 (77): (…) Cum enim fidem alicuius bonitatemque laudant, dignum esse dicunt, qui cum in tenebris mices. (“…to praise someone’s loyalty and probity, they (the philosophers) say that you could play micare with him in the dark”).

Other articles in English from the Nunc est bibendum blog