Translated from french with Deepl (please notify us of errors)

French historian Dimitri Tilloi d’Ambrosi is a specialist in Roman food. In his latest book, which has just been published, he looks at the intimate links between cuisine and health in ancient Rome. He answers our questions.

Nunc est bibendum: Isn’t it anachronistic to talk about dietetics in Roman times? Doesn’t your analysis give in to fashion?

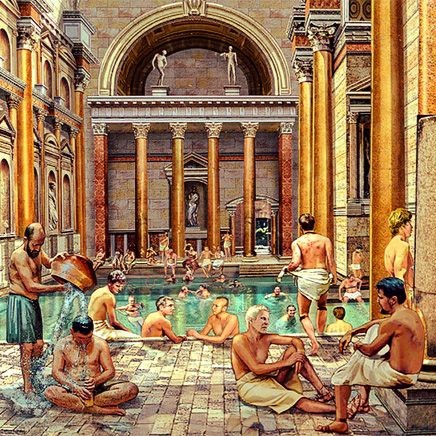

Dimitri Tilloi d’Ambrosi: The term dietetics may indeed seem particularly modern, given how central it is to contemporary medical concerns. However, it’s important to understand that in the Greco-Roman world dietetics had a broader meaning. It was a branch of medicine in its own right, covering not only diet, but also physical exercise, baths, massages – in short, anything that could influence the body’s equilibrium and form part of a complete lifestyle.

You write that food is an object of total history, that social, cultural, economic, philosophical, religious, medical and political issues are all intertwined on the plate… Really?

The history of food is not simply a matter of making a list of the foods eaten on a daily basis, but rather a historical analysis of how food reveals social, economic and cultural structures and representations. In this way, it is truly a window onto mentalities, and ultimately helps us to better understand who the Romans were. Food is also present in a great many sources, and we can study it in economic, medical, political or even religious terms, with sacrifices, for example.

Can you explain the etymology and duality of the Latin term regimen, which gave rise to the French word ‘régime’?

The Latin term regimen refers to more than just a diet. It can also be used to describe the conduct of a ship or the state, and by extension, the art of managing one’s life well.

Was the Roman regimen/diet really healthy? Pork was very much a part of the diet, and today it does not have the image of a healthy food.

The idea of a healthy diet must be understood in the light of the criteria and concepts of Hippocratic and Galenic medicine, which are not our own. If, for example, pork is healthy, it is above all for its nutritional qualities and beneficial effects on the body. Its flesh is also particularly digestible, which was very important in ancient medicine, since the balance of the humours depends on it.

Why was there such a fine line between food and medicine?

For the doctor, food and drink are first and foremost a means of nourishing oneself, maintaining health or correcting it. Food is therefore just one of the many ways in which doctors can influence the body, and in particular the balance of the human body, in the same way as they would administer remedies or bleed, for example. It’s not anachronistic to think of food as an ‘alicament’, in other words, a functional food.

You point out that Greek comedy poked fun at cooks and doctors. Yet in the Roman world, these activities were often carried out by Greeks. How do you explain this?

Plautus’ comedies of the Republican period often mocked cooks and doctors for their shortcomings, and also used stereotypes from Greek comedy. They are portrayed as deceitful and untrustworthy. It should also be remembered that Rome’s conquests in the Hellenistic East brought a large number of slaves to Rome, including representatives of these two professions, which were not highly valued in social terms. It should also be remembered that the art of gastronomy and, even more so, the art of medicine in Rome were largely the result of cultural transfers from the Greek world.

The theory of ‘humors’, which need to be balanced, has no scientific validity… But would you say that the Roman precepts are still valid?

Modern medicine obviously invalidates the humoral theories. Nevertheless, among the precepts of the Hippocratic or Galenic physician, the question of moderation, diversity of diet, a well-regulated lifestyle, including physical exercise, and the importance of a plant-based diet, are all precepts that are still relevant today.

When the ancients described the effects of food, they often spoke of ‘tightening’ or ‘loosening’ the stomach. What does this mean?

Medical texts, especially those of Galen in Roman times, pay particular attention to the effects of food and drink on the stomach, since it is considered that the humoral balance depends on good digestion. Food was cooked a second time in the stomach, according to the theory of coction, before being disseminated throughout the body. Food can help the stomach to function, either by tightening it in the event of excessive evacuation… (diarrhoea, in short…) or in the event of constipation, for example. More broadly, the aim is to stimulate and modulate the way the stomach functions. It should also be remembered that food hygiene was poor in ancient societies, not least because of the many parasites that can cause intestinal problems. So it’s easy to understand the importance of the precepts relating to the stomach.

Why do you describe the relationship between cooks and doctors as ambiguous?

One might assume that the pleasures of the table do not go well with the preservation of health, and Galen was quick to condemn certain practices of cooks and gourmets. This was also the case with the Stoic Seneca, who drew up a severe indictment of culinary sophistication. However, a detailed analysis of Galen’s work – and this is a central point of the book – reveals, on the contrary, that the physician, through his precepts, seeks to supervise and accompany the pleasures of the table in such a way as to reconcile them with health.

Doctor and cook: who has more influence on the other?

It’s difficult to say who was more influenced by the other, but Galen observed cooks’ practices very closely and sometimes tried to correct them. What’s more, a study of some of the recipes in Apicius’ collection clearly shows how dietetics was integrated into cooking. In any case, it is certain that there was a reciprocal influence, a form of complementarity emerging, rather than a strict hierarchy.

Is taste important even for doctors?

Taste is at the heart of the cuisine defined by doctors. Taste is not simply a sensation, but provides information about the properties of food. Taste can also have an effect on the body, acting as a genuine active principle. This is particularly true of bitter flavours, which can stimulate digestion.

For the Ancients, was wine also a remedy?

Wine had many uses in ancient medicine: it was good for digestion, the blood, the nerves and the stomach, for example. It is also a guarantee of longevity. Some doctors even specialised in the use of wine for health. So it can be a real remedy.

How did the reputation of the cook evolve in Roman antiquity?

The image of the cook oscillates between praise and blame in Roman texts, but it all depends on their nature. Writers of comic theatre may mock him and present him with suspicion, while moralists such as Seneca clearly condemn him for the consequences of his art on the body. On the other hand, in the work of writers like Athenaeus of Naucratis, the cook is valued and presented as an artist, even a scholar. In these texts, the cook is more a literary creation than a faithful reality. In any case, the diversity of cooks must also be taken into account: from the simple tavern cook to those in the imperial palace, there is a wide gap in terms of knowledge and skills.

What about the doctor?

Here too, it all depends on the source. Authors such as Cato and Pliny the Elder may have been wary of Greek doctors, particularly because they put their lives in the hands of strangers in exchange for money. For them, it was better to treat oneself with products from one’s own plot of land, such as cabbage for Cato. In any case, Galen, proud of his profession, tended to put the doctor on a pedestal, since he also had to be a philosopher.

Why is Greek the language of gastronomy and dietetics?

In Rome, medicine, like gastronomy, was largely Greek, so the Greek language was necessary, especially in medicine, to fully grasp all the subtleties of this knowledge, which sometimes posed a few difficulties for Latin speakers, as some ancient authors acknowledge.

Could you comment on this quotation from Plutarch: ‘it is in the body of the person being fed that the best seasonings are found’?

Plutarch, who praised the merits of simple food, was perplexed by the complex mixtures of food and numerous aromatic products that caused illness and indigestion. In his opinion, vinegar and salt are enough to season food. He explains that, in the end, the body and its reactions are enough to appreciate the flavours of such frugal food. It should also be added that, in ancient concepts, the body is like a cooking body, in which the metabolisms also contribute to transforming and assimilating the food.

Did you have to be rich to eat healthily?

Galen made a clear distinction between the rich and those of limited means. He recognised that the diversity of foods required for the diet made it more difficult for the poorest people to access it. In addition, the necessities of work and the difficulty of freeing up time for themselves and for taking care of their bodies meant that the lower social classes were condemned to poorer health. The rigorous and complete implementation of the diet tends to be aimed at the elite. However, I suggest in the book that there is also a form of popular dietetics.

Suetonius recounts the frugality of the emperor Augustus. So food also has a political significance?

Imperial biographies, such as those of Suetonius and the Historia Augusta, clearly show that the emperor’s diet was an eminently political issue. In the case of Augustus, the model of the good emperor, the frugality of his meals meant that he paid little attention to pleasures in order to devote himself fully to the affairs of the Empire. Conversely, the bad emperor was one who devoured the Empire’s riches.

Unlike health, religion doesn’t seem to play much of a role in food, is that true?

In the religious sphere, food is essential for sacrifices and offerings. On the other hand, there aren’t really any religious prohibitions; they remain very marginal. Wine is also essential for libations. There were also funeral banquets, where the sharing of food united the living around the memory of the dead.

Le régime romain

Dimitri Tilloi d’Ambrosi

Presses universitaires de France (PUF)

Paris

Octobre 2024

Other articles in English from the Nunc est bibendum blog