Translated from french with Deepl (please notify us of errors)

In the West, cheese is a must. Switzerland, France and Italy, for example, have several hundred varieties. The importance of this food has a long history. Historians generally agree that the mastery of cheese-making techniques dates back to the ancient Neolithic period, more than 5,000 years before our era, and that it closely follows the domestication of dairy ruminants: sheep, goats, cows, buffaloes, camels…

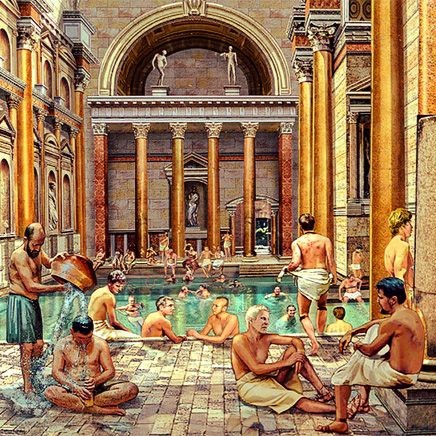

In the Greek and Roman worlds, the art of cheese-making took on such importance that authors used it as a criterion of cultural differentiation. Thus, according to the Greek geographer Strabo (1st century BC) and the Roman naturalist Pliny (1st century AD), the consumption of raw milk, yoghurt or butter characterises the barbarian, whereas the Greek or Roman taste was for refined tommes. This doesn’t hold true, of course, because milk was also consumed in the Greco-Roman orbit, particularly in the countryside, but also because the Celts also mastered cheese-making, as archaeology has shown. In 2021, for example, a study showed that the Iron Age population at the Hallstatt site (in present-day Austria) consumed blue-veined cheese, a variety of cheese unknown in the Mediterranean world.

Rennet and semen, same function

What makes cheese is the transformation of milk by the addition of rennet, which causes it to coagulate, separating the solid curds from the whey. For ancient authors, this process was as providential as the making of children. “The woman’s menstrual period is the material of the child, just as milk is the material of the cheese, fertilisation being carried out by a male semen, which is sperm in one case and rennet in the other”, explains Dominique Frère.[1]

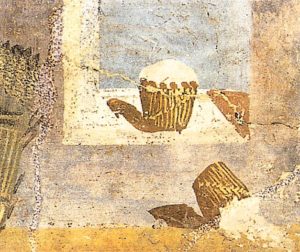

Once the curds have been obtained, the process of shaping begins (the Latin word forma is the source of the french word “fromage”). Three ancient authors provide information on Roman cheese-making: Columella and Pliny in the 1st century and Palladius in the 4th. Information is also compiled in a slightly later Byzantine text, the Geoponics, dating from the 7th century.[2] These texts describe all the stages that still make up the cheese-making process today: moulding, draining, flavouring, salting, washing, etc. Culturally, the Romans did not appreciate rotting and valued soft foods, so it was naturally fresh cheese that was most appreciated. The texts do not mention “bloomy crust” or “blue-veined” cheeses (unlike in the Celtic world, as we saw above). But that doesn’t mean that these types of cheese were unknown: the aim of an agronomist like Columella was not to list all the skills involved, but to indicate the most “efficient” process, as we would say today.

Mozzarella are you there (at Columelle’s)?

Columelle, however, makes an interesting digression, which will finally justify the title of this article. Here is his text:

Everyone knows the way of making cheese which we call pressed by hand (manu pressum). When the milk begins to coagulate in the milking vat, and is still warm, it is divided into slices, dipped in boiling water, and given a shape of some kind by hand, or pressed in boxwood moulds. Made firm by the brine, it does not have an unpleasant flavour when it has been coloured with smoke, either from apple wood or stubble.[3]

The process is remarkably similar to that of the famous mozzarella, a cheese traditionally made in a region of Italy stretching from Lazio to Puglia. In both cases, the curds are cut, immersed in boiling water, formed into balls and preserved in brine.

Of course, the cheese described by Columella is not exactly mozzarella, if only because this name, derived from the Italian mozzare (to slice), did not appear until the 16th century, first mentioned in 1570 by Bartolomeo Scappi, a cook at the papal court.

Another dissonance is that mozzarella was originally produced mainly from the milk of buffalo, whose presence in Campania is attested as far back as the 12th century. But the arrival of these animals, originally from India, is the subject of much debate. According to one theory, they were introduced to southern Italy by the Normans from Sicily, brought by the Arabs. Another theory is that buffaloes arrived in Italy via the Phoenicians from India, which would make it possible that buffalo milk was used in ancient times, but there is no proof of this either in texts or archaeology…

Although Columelle’s text does not describe contemporary mozzarella, it does bear witness to the remarkable permanence of agricultural and craft skills, which have survived the ages as empires have been created and broken up.

[1] Dominique Frère, Fromages antiques, à la recherche des fromages disparus, Presses universitaires de Rennes (PUR), Rennes, 2024, p. 37.

The analogy is already present in Aristotle (Generation of Animals, I, XIV, 729a):

“It is the male that brings form and the principle of movement; the female brings body and matter, just as, in the coagulation of milk, it is the milk that is the body, while it is the whey, the rennet, that has the coagulating principle. This is also the same action produced by what the male brings, by dividing, into the female.”

ἐπειδὴ τὸ μὲν ἄρρεν παρέχεται τό τε εἶδος καὶ τὴν ἀρχὴν τῆς κινήσεως τὸ δὲ θῆλυ τὸ σῶμα καὶ τὴν ὕλην, οἷον ἐν τῇ τοῦ γάλακτος πήξει τὸ μὲν σῶμα τὸ γάλα ἐστίν, ὁ δὲ ὀπὸς ἢ ἡ πυετία τὸ τὴν ἀρχὴν ἔχον τὴν συνιστᾶσαν, οὕτω τὸ ἀπὸ τοῦ ἄρρενος ἐν τῷ θήλει μεριζόμενον.

[2] Columelle, Traité d’agronomie, VII, 8; Pline, Histoire naturelle, XI, 96-97 et XXVIII, 34; Palladius, Traité d’agriculture, VI, 9 ;Géoponiques, XVIII, 19.

[3] Columelle, Traité d’agronomie, VII, 8, 7: Illa vero notissima est ratio faciundi casei, quem dicimus manu pressum : namque is paulum gelatus in mulctra, dum est tepefactus, rescinditur, et fervente aqua perfusus, vel manu figuratur, vel buxeis formis exprimitur. Est etiam non ingrati saporis muria praeduratus, atque ita malinis lignis, vel culmi fumo coloratus.

To find out more

- France Culture, Carbone 14, the magazine of archaeology, La bande à Nectaire… En plateau, affinons l’histoire du fromage!, April 2022,

- Alain Ferdière and Jean-Marc Séguier, Le fromage en Gaule à l’âge du Fer et à l’époque romaine: état des lieux pour sa production et analyse de sa place dans le monde antique, Gallia [On line], 77-2 | 2020, online since 25 February 2021.

January 2024, reproduction prohibited

Other articles in English from the Nunc est bibendum blog