Translated from french with Deepl (please notify us of errors)

The most basic method of creating pleasant scents was to burn branches, gums, resins or aromatic mixtures. It was probably in temples that the art of perfumery flourished, through the use of purifying fumes in honour of the divinities.

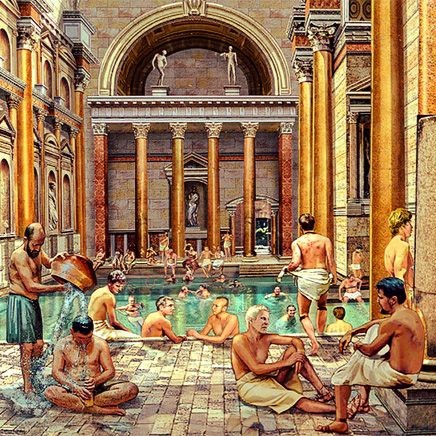

But it wasn’t long before humans also wanted to smell divine. The battle was not won. While divinities naturally smell good, mortals do not. So perfume, or more precisely perfumed oil or water (and incidentally hygiene and thermal baths), had to be invented.

When was this invention invented? In the first century, the naturalist Pliny pondered the question:

Perfumes must be for the Persians. They flood themselves with it and use this palliative to suffocate the bad smell caused by their uncleanliness. The first mention I can find of it is that when the camp of Darius was taken, Alexander took a perfume box from among all the royal equipment.[1]

Pliny does not seem to have had access to sufficiently reliable sources on this point: archaeology has shown that, as early as the 3rd millennium BC, perfumers were at the service of the gods and the powerful in Mesopotamian, Egyptian and Cretan palaces.

Trade and flask

Pliny’s error can no doubt be explained by the fact that it was not until the Hellenistic and then the Roman periods that perfumes really diversified and became more democratic. There were two reasons for this.

The first was the increase in trade with Arabia – the land of frankincense and myrrh – and India, rich in fragrant spices.

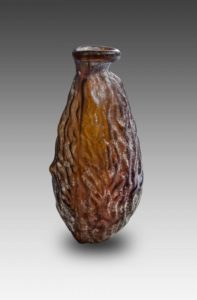

The second was the mastery of the glass-blowing technique, which made it possible to create delicate, highly elaborate bottles, but above all, which preserved the fragrances much better.

Indeed, one of the difficulties in perfumery is to prevent the aroma from becoming stale or fading. This volatility gave Pliny a ready-made argument to criticise excessive spending by perfumers:

Such is this object of luxury, and of all the most superfluous. Pearls and jewels pass on to their heirs, fabrics last a certain time: perfumes evaporate instantly and, as it were, die as they are born. The highest recommendation of a perfume is that, when a woman who wears it passes by, its very scent attracts those who are occupied with anything else.[2]

It has to be said that some powerful men did not skimp on the bottle. Nero, it is said, perfumed himself right down to the soles of his feet, and Caligula had his baths sprinkled with it. All these things were reminiscent of the debauched luxury of the kings of the East, far removed from austere Roman morality.

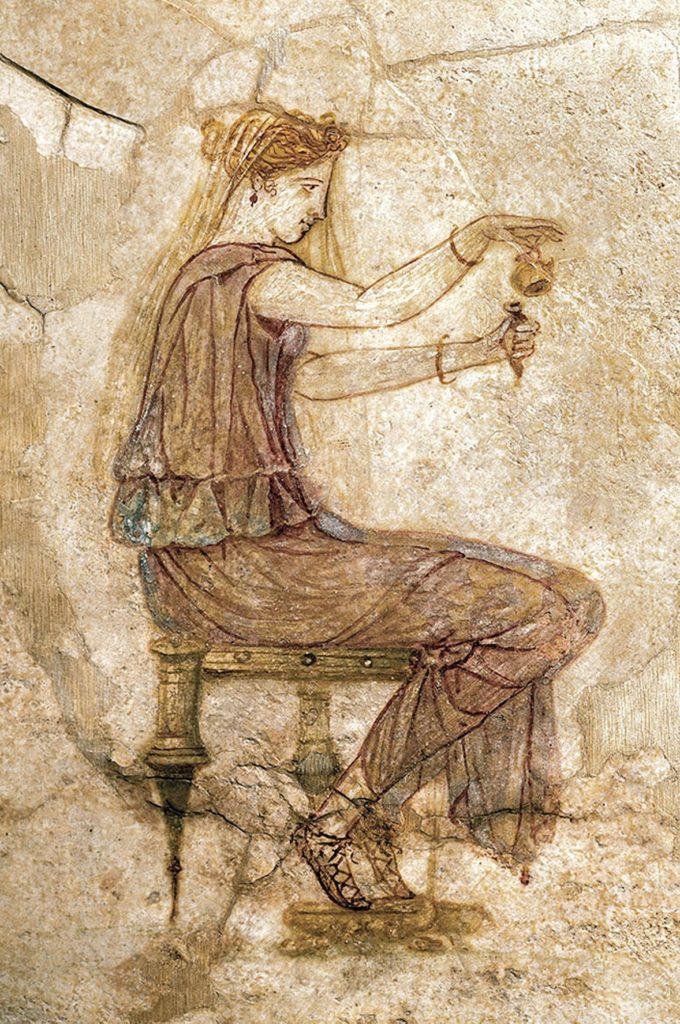

We also read in the same passage of Pliny’s work that perfume was an instrument of seduction. In fact, ancient texts abound with examples of bodies being oiled and perfumed to arouse desire. Aphrodite, the goddess of love, was linked to flowers and scents from the moment she was born on “fragrant Cyprus”, as Homer put it.

So it’s easy to understand why Pliny shuddered when he realised that perfumes had even conquered the mighty Roman army. Military ensigns were smeared with perfume on feast days, and some even believe that this enabled the Roman eagles to conquer the earth:

These are the patronages we seek for our vices, and we use them to justify the perfumes under the helmet.[3]

Sucus and corpus

But Pliny did more than just criticise: in his Natural History, he detailed the composition and manufacture of ancient perfumes. He distinguishes between sucus (the odorous substance) and corpus (the excipient). As strong alcohol was unknown in Antiquity, oil was generally used as the corpus. Olive oil was the most common, but sesame oil (which had the advantage of being odourless), moringa oil and almond oil were also used. Theophrastus[4] provides a list of the oils used.

Fixing agents such as resins, colouring agents such as alkanet[5],and preservatives, mainly salt, are also sometimes used.

Honey is also used to coat perfume containers, probably because of its antioxidant and antiseptic properties.

Scented substances – or sucus – are very numerous. In the earliest times, fragrant woods – cedar, cypress or juniper – were the most widely used. But in the Hellenistic and Roman eras, plants, gums and spices came to the fore (see list below).

A contemporary of Pliny, the physician Dioscorides gives a comprehensive list of the perfumes of the time. He details each recipe, which bears the name of its main ingredient, the town where it was created or its inventor. He also explains how to make a product of lesser quality by adding oil to the substrate already used and filtered. There was therefore a range of different qualities of the same perfume, making the lower quality version accessible to less wealthy people.

Dioscorides was primarily interested in the therapeutic virtues of perfumes, which were confused with ointments. The professions of perfumer and druggist were not clearly distinguished.

In ancient times, you could treat yourself by smelling nice. And vice versa. Some even dared to add perfume to their food. Needless to say, this is strongly discouraged today.

Ancient fragrances

Here is a non-exhaustive list of the suci most commonly used in Roman perfumery.

Flowers: Jasmine (Jasminum grandiflorum, Jasminum sambac); Rose (Rosa centifolia/Rosa damascena); Narcissus (Narcissus poeticus); Lily (Lilium candidum); Henna (Lawsonia inermis); Marjoram (Origanum majorana).

Rhizomes: Iris (Iris pallida); Spikenard (Nardostachys jatamansi).

Gums and resins: Myrrh (Commiphora myrrha); Judas balsam (Commiphora opobalsamum); Styrax (Liquidambar orientalis); Frankincense (Boswellia carterii); Labdanum (Cistus ladaniferus); Galbanum (Ferula galbaniflua).

Spices: Cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum); Cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum); Saffron (Crocus sativus); Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum).

[1] Pliny, Natural History, XIII, I, 3: Unguentum Persarum gentis esse debet. Illi madent eo et accersita commendatione inluvie natum virus extinguunt. Primum, quod equidem inveniam, castris Darii regis expugnatis in reliquo eius appartu Alexander cepit scrinium unguentorum.

[2] Pliny, Natural History, XIII, IV, 20: Haec est materia luxus e cunctis maxime supervacui. Margaritae enim gemmaeque ad heredem tamen transeunt, vestes prorogant tempus: unguenta ilico expirant ac suis moriuntur horis. Summa commendatio eorum ut transeuntem feminam odor invitet etiam aliud agentis.

[3] Pliny, Natural History, XIII, IV, 23: Ista patrocinia quaerimus vitiis, ut per hoc ius sub casside unguenta sumantur.

[4] Theophrastus, On Smells, 14.

[5] Alkanna tinctoria, a prostrate, very low, very hairy plant, grows most often on coastal sands, in more or less circular clumps. It has been used since ancient times for its medicinal properties, as well as for the red dye extracted from its roots.

Sources

- Odeurs antiques, texts collected and presented by Lydie Bodiou and Véronique Melh, collection Signets, Belles-Lettres, Paris, 2011.

- Jean-Pierre Brun, Cécilia Castel, Xavier Fernandez, Jean-Jacques Filippi, Les parfums antiques dans le bassin méditerranéen, article published in l’Actualité Chimique N°359 – January 2012. Accessed online on 4 February 2024.

- Video: animation by Renaud Chabrier of a fresco in Pompeii showing the manufacture of perfume, produced for the film Le parfum retrouvé (link below). All the stages in the preparation of perfumes in a shop are shown from right to left: 1. extraction of the perfume oil with a wedge press, 2. hot enfleurage of the oil in a cauldron on a hearth, 3. grinding of the ingredients, in particular resins, in a mortar, 4. sales counter with scales, papyrus and, in the cupboard in the background, rows of perfume bottles and a statuette of Venus, 5. a sales assistant has a customer try a perfume on her wrist.

To find out more

- Le parfum retrouvé, written and directed by Luc Renat, CNRS images, 2012.

- Jean-Pierre Brun and Nicolas Monteix, Les parfumeries en Campanie antique In : Artisanats antiques d’Italie et de Gaule: Mélanges offerts à Maria Francesca Buonaiuto [online]. Naples: Publications du Centre Jean Bérard, 2009.

February 2024, reproduction prohibited

Other articles in English from the Nunc est bibendum blog