Translated from French with DeepL & ChatGPT (please notify us of errors)

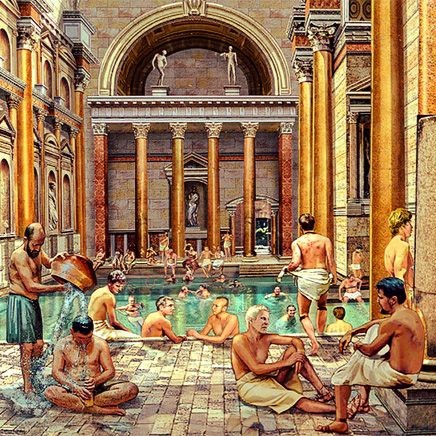

On this day in Rome, there were reports of naked men running unrestrained through the streets, wielding goat thongs to whip any woman they encountered. The purpose of this crude ritual was to supposedly enhance the women’s fertility.

These youthful messengers were dispatched by the Luperci, a group of wolf-men and priests who worshiped Faunus, a primitive and horned deity believed to govern the forests, plains, and fields. Revered as a willing lecher and fertility-god for herds, he was often compared to the Greek god Pan. Annually, the brotherhood of the Lupercus gathered in mid-February at the Lupercal cave situated at the base of Mount Palatine, where legend holds that the she-wolf had nursed Romulus and Remus, the founders of Rome. There, they conducted the ritual sacrifice of one or more goats, billy goats, or goats and also a dog, as the latter is the natural enemy of wolves.

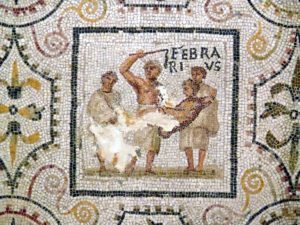

The ritual in question is chronicled by Plutarch, a Roman author who wrote in Greek and was born in 46 AD:

…During the ceremony, two young men from the most prominent families of Rome were selected, and their foreheads were pricked with a bloody knife before being quickly wiped clean with wool soaked in milk. Following this, they were compelled to laugh, after which the Luperci fashioned whips from the skin of the sacrificial goats. Running through the streets naked, save for a simple leather belt, they would strike anyone they came across with these whips.[1]

The race is conducted in the most basic attire, but the reason behind this custom remains enigmatic. The Roman poet Ovid, who lived at the dawn of the first century, provides a range of explanations for this practice. Among these, one particularly titillating suggestion stands out.

Legend has it that on a certain day, Faunus caught sight of the mighty hero Hercules walking alongside his stunning companion, Omphale. The horned deity was instantly consumed by an intense desire for the young woman. The couple sought refuge in a cave, where they proceeded to playfully switch garments before retiring to separate beds. Unwavering in his lust, Faunus stealthily made his way into the cave, groping blindly until he reached the first layer of bedding. There, upon recognizing the familiar feel of the lion’s skin draped across Hercules, he promptly retreated.

…Faunus then noticed another bed nearby, which was adorned with soft and delicate fabrics. He allowed himself to be swayed by the bed’s seductive allure and climbed atop it. The intensity of his desires was such that the mere stiffness and rigidity of his horns would have been inadequate to convey its full force. Driven by an insatiable yearning, he began to lift the tunic slightly, only to be confronted by a pair of hairy, rough, and bristling legs.[2]

It goes without saying that Hercules, even though dressed in women’s clothes, does not let himself be pushed around. That is why Faunus, ridiculed, cannot bear anyone who appears before him dressed up.

Ovid also recounts the legend behind the goat thongs’ supposed power to bring fertility.

In in the early days of Rome, Romulus was despondent as the women he had taken from the Sabines proved to be barren. However, in a sacred grove dedicated to the goddess Juno at the base of the Esquiline Hill, the deity suddenly spoke in a rustle of leaves:

Mothers of Latium, she says, let a sacred goat penetrate you![3]

The crowd is speechless… and also a little shocked by this confusing oracle. But fortunately for the Sabines, an augur has the idea of immolating a goat:

He made a whip from the skin of the victim, cut into strips, and the women, docile to the order they received, came to offer themselves to his blows. For the tenth time the moon brought its renewed crescent into the heavens: the husband had become a father, the wives had given birth.

And so the Roman people were able to grow… and to indulge every year in a joyful stampede of naked men running through the streets.

Some modern commentators also report that the race was followed by a banquet during which a love lottery took place, with young men and women being drawn to form couples, whether or not they would last. But we have not found any ancient source that supports this idea.

Even without this, the sexual connotations of the ritual are obvious, even if things were to remain generally symbolic. For Romans steeped in gravitas -retention and moral rigour- the primitive, wild and unbridled character of the Lupercalia must have been difficult to swallow. Cicero, moreover, echoes the bad reputation of the festival[4]. To limit the excesses, the emperor Augustus forbade the Lupercalia race to beardless boys[5]. First turn of the screw.

The festival continued for several centuries, but for the triumphant Christianity, it was too much. In 494, Pope Gelasius I decided to do something drastic: he banned the Lupercalia and dedicated 14 February to Valentine, a priest of the 3rd century, a matchmaker and himself in love, who was executed by the emperor of his time. It was not until 1496 that the papacy made Valentine the patron saint of lovers, with the success that we know, until the desacralized, syrupy and commercialized festival of today.

Contrary to common belief, it is difficult to see a direct link between the Lupercalia and Valentine’s Day. But it is certain that the latter has very conveniently overshadowed the former.

[1] Plutarch, Lives of the Illustrious Men, Volume 1, Life of Romulus: (6)… εἶτα μειρακίων δυοῖν ἀπὸ γένους προσαχθέντων αὐτοῖς, οἱ μὲν ᾑμαγμένῃ μαχαίρᾳ τοῦ μετώπου θιγγάνουσιν, ἕτεροι δ’ ἀπομάττουσιν εὐθύς, ἔριον βεβρεγμένον γάλακτι προσφέροντες· (7) γελᾶν δὲ δεῖ τὰ μειράκια μετὰ τὴν ἀπόμαξιν. Ἐκ δὲ τούτου τὰ δέρματα τῶν αἰγῶν κατατεμόντες, διαθέουσιν ἐν περιζώσμασι γυμνοί, τοῖς σκύτεσι τὸν ἐμποδὼν παίοντες. Αἱ δ’ ἐν ἡλικίᾳ γυναῖκες οὐ φεύγουσι τὸ παίεσθαι, νομίζουσαι πρὸς εὐτοκίαν καὶ κύησιν συνεργεῖν.

[2] Ovid, Fastes, II, 343-348: Inde tori qui iunctus erat uelamina tangit / mollia, mendaci decipiturque nota. / Ascendit spondaque sibi propiore recumbit, / et tumidum cornu durius inguen erat. / Interea tunicas ora subducit ab ima: / horrebant densis aspera crura pilis.

[3] Ovid, Fastes, II, 441/445-448: ‘Italidas matres’ inquit ‘sacer hircus inito. (…) ille caprum mactat: iussae sua terga puellae pellibus exsectis percutienda dabant. Luna resumebat decimo noua cornua motu, virque pater subito nuptaque mater erat.

[4] Cicero, For Caelius, XI, 26: «Truly fierce, entirely pastoral and rude, this brotherhood of the real wolves, whose savage association was evidently created before civilisation and laws, since its confreres not only accuse each other in court, but also remind each other of their confraternity by doing so, as if they feared that someone might ignore it by chance.» / Fera quaedam sodalitas et plane pastoricia atque agrestis germanorum Lupercorum, quorum coitio illa siluestris ante est instituta quam humanitas atque leges, si quidem non modo nomina deferunt inter se sodales sed etiam commemorant sodalitatem in accusando, ut ne quis id forte nesciat timere uideantur!

[5] Suetonius, Life of Augustus, XXXI, 5-6.

Other articles in English from the Nunc est bibendum blog