Translated from French with ChatGPT (please notify us of errors) – Article en français

Heatwaves are sweeping across Europe. Interestingly, the ancient Romans too grappled with stifling summers. They referred to this sweltering period with a Latin term we still use today: “canicula.”

The heatwave’s history is written in the stars. Over 3,000 years ago, a constellation caught the eye of Babylonian astronomers. And for a good reason: nestled within this cluster of stars is the brightest one in our sky.

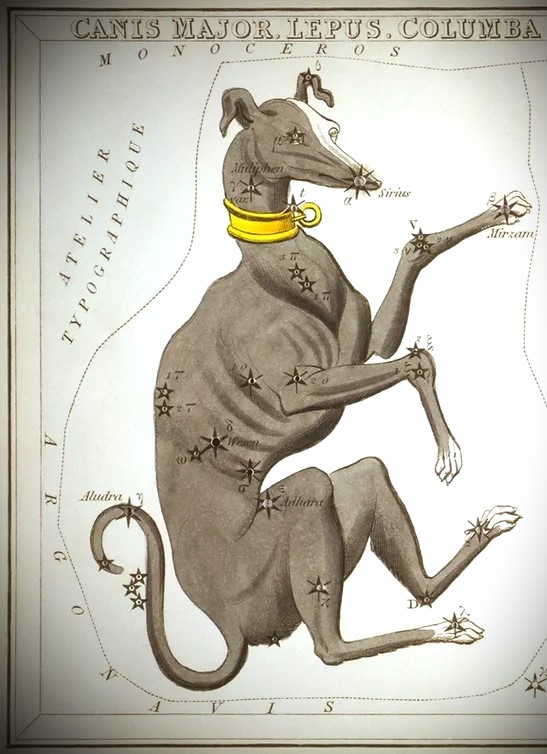

While the Babylonians interpreted these stars as an arc and an arrow, the Greeks, centuries later, believed they saw the shape of a grand dog. This wasn’t just any dog. Sometimes, it was identified as Sirius, one of the hounds of the hunter Orion; other times as Laelaps, the companion of the hunting goddess Artemis, successively gifted to King Minos of Crete, the beautiful Procris, and then to Cephalus, the king of Athens. Ultimately, Zeus transformed Laelaps, who could run twice as fast as its prey, into a constellation.

From the Grand Dog to the Little Dog

The Romans adopted the narrative of the “Canis major” constellation. However, they also identified a smaller celestial cluster nearby. The two brightest stars of these neighboring constellations still bear the names of Orion’s dogs: Sirius and Procyon [1].

In Roman times, Sirius had the unique characteristic of rising and setting simultaneously with the sun between July 22 and August 22, aligning with the peak heat period.

As its Greek name suggests, Procyon preceded Sirius in the sky, heralding the impending intense heat.

Cave caniculam!

But what’s the connection with the Latin term “canicula,” which gave birth to our “canicule”? The answer lies in the somewhat technical explanations of the naturalist Pliny the Elder:

“From the summer solstice until the setting of the Lyre, Orion rises, according to Caesar, on the 6th day before the calends of July (June 26); on the 4th day before the nones (July 4), his belt rises in Assyria, and in Egypt, the scorching Procyon rises in the morning. This constellation has no name among the Romans unless we understand it as Canicula, as it is depicted among the stars; it is of great significance, as we will explain shortly.”[2]

If you’re still lost, here’s a summary: The constellation identified by the Romans, neighboring the Grand Dog, Canis Major, but smaller, is none other than Canicula, which translates to “little female dog” in Latin. And its arrival in the sky spells trouble.

The myth of Icarios, Erigone, and Maera

A lesser-known author, Hygin, who lived during the time of Augustus, narrates a rather grim tale about this mythological little dog.

According to him, she was named Maera and belonged to Erigone, the daughter of the Athenian Icarios, who was taught viticulture by Dionysos. As Icarios generously tried to impart his wine-making knowledge to shepherds, they, in a drunken stupor, murdered him. Maera, in her anguish, led her mistress to the crime scene. Discovering her slain father, Erigone hung herself. The dog’s grief intensified, leading her to leap off a cliff.

The gods, enraged by this senseless tragedy, meted out various punishments to the culprits and elevated the victims to the heavens: Erigone became the Virgo constellation, Icarios the Boötes, and Maera was equated with the Canicula constellation.[3]

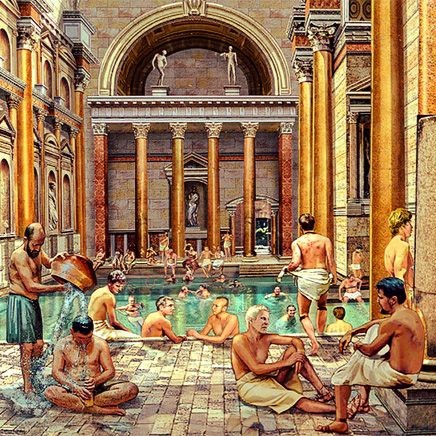

Shielding from the Scorching Heat

However, Maera’s ascent to the sky was a dire omen for humans. Pliny lists some of the heatwave’s afflictions:

“Who doesn’t know that the rising of the Canicula intensifies the sun’s rays? This constellation has the most potent effects on Earth: when it rises, the seas boil, wine ferments in cellars, and marshes stir. The Egyptians named an animal ‘oryx,’ which, they believe, stands facing this constellation as it rises, gazing at it as if in worship, after sneezing. It’s undeniable that during this period, dogs are especially prone to rabies.”[4]

To guard against the heatwave’s devastating effects, the Romans instinctively thought of a solution: a sacrifice to appease the gods. And what better victims than red-haired female dogs[5], whose fur color mirrors the sun’s fervor?

Pliny and a few other authors mention this sacrificial ceremony aimed at warding off heat-related disasters and safeguarding the crops, known as the “augurium canarium.” It seems this ritual was observed at the onset of summer at the “porta Catularia,” located west of the Capitoline Hill[6].

Dogs, humanity’s companions even before the advent of writing and valued as hunting partners, guardians, pets, and shepherds, received a grim recompense from the Romans for their unwavering loyalty: truly, a dog’s life!

[1] Sirius, σείριος in ancient Greek, means “burning, blazing”; and Procyon, προκύων, translates to “dog that leads, barker.”

[2] Pliny the Elder, Natural History, XVIII, 48 (268): Ab solstitio ad fidiculae occasum VI kal. Iul. Caesari Orion exoritur, zona autem eius IIII non. Assyriae, Aegypto vero procyon matutino aestuosus, quod sidus apud Romanos non habet nomen, nisi caniculam hanc volumus intellegi, hoc est minorem canem, ut in astris pingitur, ad aestum magno opere pertinens, sicut paulo mox docebimus.

[3] Hygin, Fables, 130. Icarios and Erigone.

[4] Pliny the Elder, Natural History, II, 107: Nam caniculae exortu acendi solis vapores quis ignorat? cuius sideris effectus amplissimi in terra sentiuntur: fervent maria exoriente eo, fluctuant in cellis vina, moventur stagna. orygem appellat Aegyptus feram, quam in exortu eius contra stare et contueri tradit ac velut adorare, cum sternuerit. canes quidem toto eo spatio maxime in rabiem agi non est dubium.

[5] Festus p. 358,27 sous Rutilae canes.

[6] Digital Augustan Rome, Porta catularia.

Furthermore (in French)

- La canicule, un temps de chien(ne)! Une carte mentale de l’association Arrête ton char! qui interroge l’origine du mot canicule.

- Constellation du Grand chien, sur le site Ciel de nuit, introduction à l’astronomie et l’astrophysique.

First published in August 2023, reproduction prohibited.

Other articles in English from the Nunc est bibendum blog