Translated from french with Deepl (please notify us of errors)

A skilful military strategist, a sensible statesman, loved by his soldiers and the people. And generous. Emperor Trajan was highly praised, both by his contemporaries and by ancient historians. In fact, it was under the reign of Optimus Princeps that the Empire reached its territorial apogee.

Among Trajan’s “generous” works, it is worth taking a close look at the Istitutio alimentaria, a measure taken in 103 AD in favour of destitute children, orphans or not, girls or boys, living in the Italian peninsula.

In his panegyric dedicated to the emperor, Pliny the Younger summed up the situation:

“It hardly amounts to less than five thousand, conscripted fathers, the number of children of free condition whom the munificence of our prince has sought out, discovered, adopted. They are brought up at the State’s expense, to be its support in war and its ornament in peace; and they learn to love the country, not only as the country, but as the mother who nurtures their young age. It is from them that the camps, from them that the tribes will one day be populated; from them will in turn be born offspring to whom this public help will no longer be necessary.”[1]

Money lent by the emperor

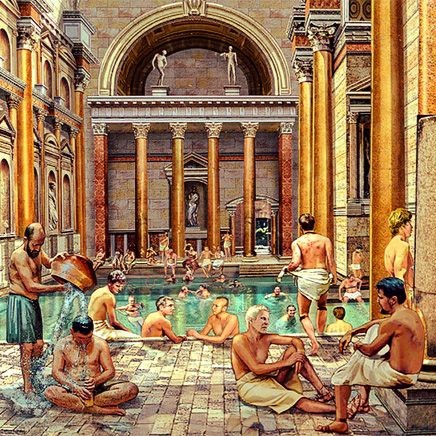

Let’s leave Pliny to his praise and take a look at how the process worked in practice. The Emperor began by lending money from his own estate to farmers. The farmers had to guarantee a mortgage on their property and agree to pay an annual interest rate of 5%. The Obligatio praediorum was born. The money raised was used to feed poor children.

Pliny the Younger was in awe:

“There is, therefore, one thing in your munificence that I will praise more than the rest: it is that, with your generosity to the people and your food for children, what you give is yours”[2]

As munificent as it was, the imperial gesture was of course not without interest. Trajan saw two advantages: to maintain a nursery of future legionnaires, as Pliny explains in other words; and also to halt the rural exodus, since farmers had enough to invest in maintaining and cultivating their land.

To make all this work, the Romans appointed a battery of civil servants, the quaestores alimentorum, themselves under the orders of a praefectus alimentorum.

Unfortunately, this attention to detail and meticulous organisation did not leave many traces. There are two.

The first is a bas-relief on a triumphal arch dedicated to Trajan and located in the town of Benevento, not far from Naples. It shows fathers bringing their sons to a curator who is distributing food.

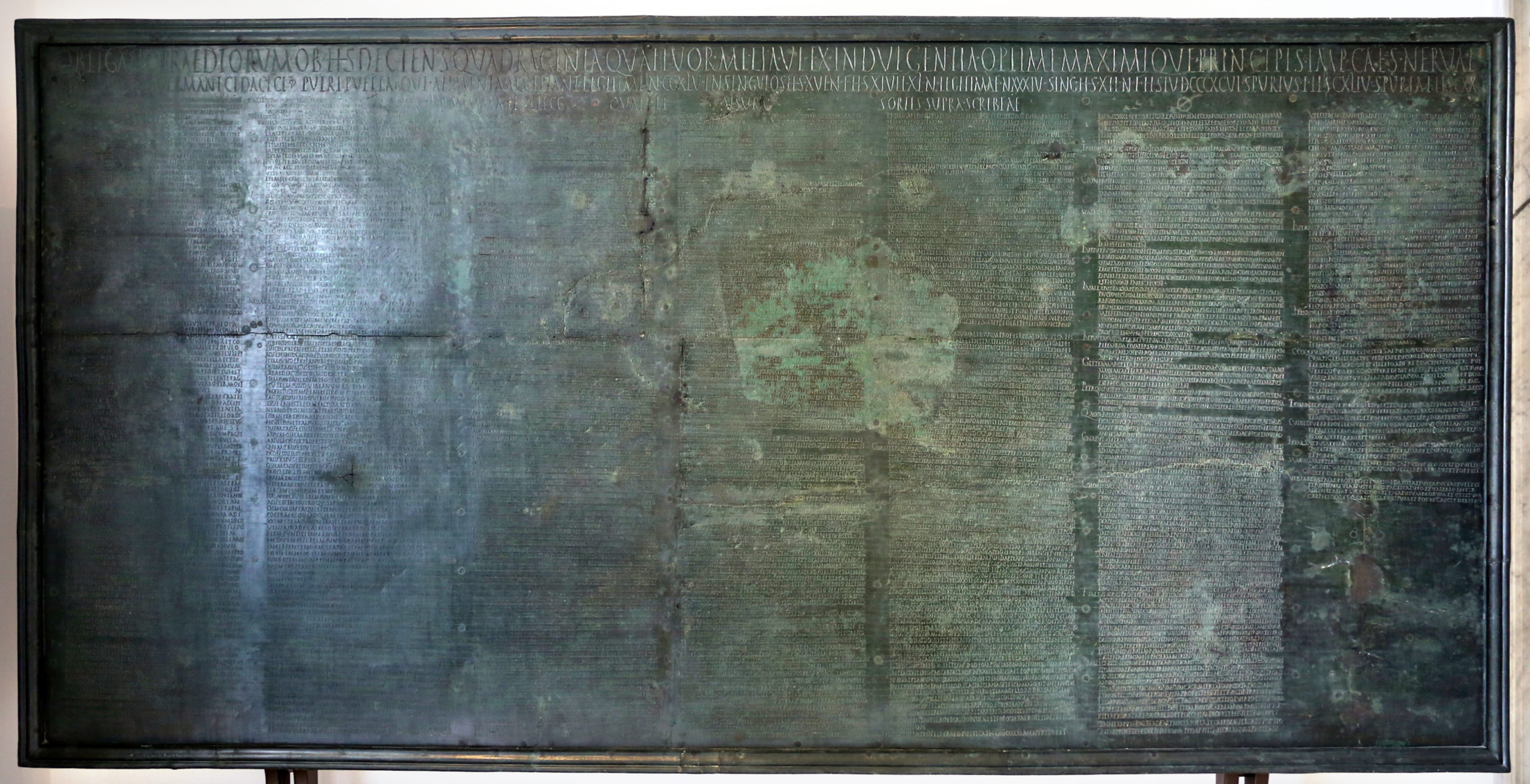

The second – and clearly more important – source for theIstitutio alimentaria is a bronze table found in the 18th century in Velleia, a charming village in Emilia Romagna at the foot of the Apennines that could be used as a stopover on the journey between the Po Valley and Liguria.

The largest Roman inscription

The 674 lines making up this Tabula alimentaria traianea written in six columns contain the commitments of 50 owners for the total benefit of 246 boys and 35 girls. There are two series of bonds: the first dates from the beginning of the 2nd century and values 72,000 sesterces; the second series of bonds stretches from 106 to 114 and is worth over a million sesterces. Amounts allocated: 16 sesterces per month for legitimate children; 12 sesterces for legitimate daughters and the same for the only illegitimate son to benefit; and 10 sesterces for the only illegitimate daughter on the table.

This famous bronze table is, in all likelihood, the largest surviving Roman inscription: it measures 2.86 metres by 1.38 metres. But once again, the table came very close to disappearing forever. Discovered by chance in 1747 during earthworks in a field near the church in Velleia, this tabula alimentaria was initially sold piece by piece to foundries in the region. But two local noblemen, Giovanni Roncovieri and Antonio Costa, managed to get their hands on the precious bronze once and for all.

The discovery prompted archaeologists of the time to undertake excavations. As a result, they were able to bring to light the remains of an ancient Roman city, the existence of which was attested by Pliny the Elder: “On this side of Piacenza, on the hills, is the city of the Velates”[3]

[1] Pliny the Younger, panegyricus, XXVIII : «Paullo minus, Patres Conscripti, quinque millia ingenuorum fuerunt, quae liberalitas principis nostri conquisivit, invenit, adscivit. Hi subsidium bellorum, ornamentum pacis, publicis sumptibus aluntur, patriamque non ut patriam tantum, verum ut altricem amare condiscunt. Ex his castra, ex his tribus replebuntur; ex his quandoque nascentur, quibus alimentis opus non sit.»

[2] Pliny the Younger, panegyricus, XXVII : «Quocirca nihil magis in tua tota liberalitate laudaverim, quam quod congiarium das de tuo, alimenta de tuo»

[3] Pliny the Elder, Naturalis historia VII 163 : «Citra Placentiam in collibus oppidum est Veleiatium»

Sources

- Jérôme Carcopino et Camille Jullian, La Table de Veleia et son importance historique, Revue des Études Anciennes, 1921, pp. 287-304.

- Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Parma. Le tre sale dedicate ai reperti rinvenuti negli scavi della città romana di Veleia.

April 2024, reproduction prohibited

Other articles in English from the Nunc est bibendum blog