Translated from French with ChatGPT (please notify us of errors)

Our winemaking tradition often evokes its Greco-Roman heritage. However, the cultivation of vines and the tradition of wine extend far beyond this geographical area and trace back to an even older past. To remember this, one needs only to think of the biblical account, which was written down over a millennium before our era, drawing from even older oral traditions. In Genesis, barely having set foot on dry land after the flood, Noah plants a vine… and gets intoxicated[1]. As for the lover in the Song of Solomon, she declares to her partner, “your caresses are sweeter than wine”[2].

According to recent research, the domestication of the vine occurred approximately 11,000 years ago in the Caucasus and Western Asia. The cultivation and its derivative products, including wine, then spread throughout the entire Mediterranean region.

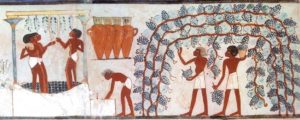

By the 3rd millennium BCE, the Egyptians were the first to depict the winemaking process on bas-reliefs showing scenes of harvesting, treading, and pressing. In pharaonic Egypt, wine, known as “irep,” was an exceptional product reserved for the elites. However, during the New Kingdom period (-1550 to -1085), texts mention a drink even rarer and more prestigious than wine: the shedeh. It is believed to be none other than the gift from the sun god Ra to his sons.

What was this mysterious shedeh made of? What was its manufacturing process? The mystery remained nearly complete until recently. Egyptian authors did not provide any information on this topic, and archaeological clues were as scarce as the product itself. No traces of vine cultivation have been found to this day. Thus, one had to rely on the rare references in texts and mural representations.

However, in 1922, the archaeologist Howard Carter discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun, the 11th pharaoh of the New Kingdom, who is more famous for his treasure than his reign, which lasted only 10 years. Among the 5,398 inventoried objects found in the tomb were eight jars with inscriptions of “shedeh” on either their stoppers or bodies. Some of them were exceptionally well-preserved, which was decisive for further investigations.

For decades, Egyptologists attempted to solve the shedeh enigma. For most Anglo-Saxon scholars, it was believed to be a pomegranate liqueur rather than grape-based.

In a 1995 publication, the French Egyptologist Pierre Tallet reexamined the case based on all available evidence, particularly the inscriptions on the jars, which, in addition to the product name, provided very specific information: origin, date, quality, domain, geographical location, and the producer’s name. Point by point, he constructed the identification profile of this mysterious beverage [3].

Firstly, the shedeh was of exceptional quality and relatively scarce. According to the only papyrus mentioning the subject during the pharaonic period, one jar of the drink was produced for every 30 jars of wine. This proportion is consistent with the jars found. Moreover, the name “shedeh” is frequently followed by the qualifier “nefer nefer,” meaning “excellent” or “very good” in Egyptian.

Secondly, Pierre Tallet established that shedeh was undoubtedly a preparation based on grapes. A key clue is that the shedeh producers had the same names as wine producers. Thus, they were “winegrowers” who used their harvest to create a range of products.

The archaeologist also noted that shedeh could be stored like a “fine wine.” Indeed, Tutankhamun’s tomb was sealed in the tenth year of his reign, and shedeh produced five to six years earlier was found there. Unless one assumes that the pharaoh was given undrinkable wine for his final journey, this indicates that the beverage could be stored without any problems for such a long time.

Lastly, Pierre Tallet believed that shedeh must have been a sweet and highly alcoholic wine. Egyptian love poetry frequently mentions it in a similar vein to the aforementioned Song of Solomon[4].

As for the alcohol content of shedeh, it could have resulted from a manufacturing process involving the reduction of must through boiling. This would increase the sugar content, which could then ferment into alcohol. Thus, an alcohol level of around fifteen degrees could be reached, preventing the wine from turning into vinegar and explaining its exceptional shelf life.

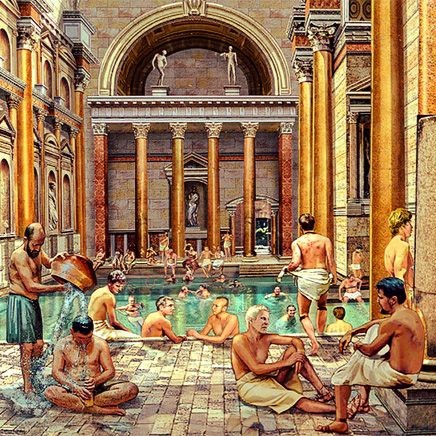

The reduction of must through boiling is a process that would later be described in detail by Roman authors. In the 1st century, Columella mentioned that it required constant monitoring and stirring to avoid burning the preparation [5]. Pliny specified that the must was reduced to one-third to produce defrutum and to half to make sapa[6].

So far, the entire investigation has relied solely on observations and deductions, subject to controversies.

However, advances in analytical methods have finally settled the matter. In the early 21st century, two Spanish scientists, Rosa Lamuela-Raventós and Maria Rosa Guasch-Jané, were granted permission to study a sample residue from a shedeh jar found in Tutankhamun’s tomb. They conclusively determined that the beverage was indeed wine, and it had been produced using red grapes[7].

We now know with certainty that the nectar consumed by the pharaohs and taken with them into the afterlife was indeed a divine fruit of the vine.

[1] Genesis, 9:20-21.

[2] Song of Solomon, 1:2.

[3] Tallet P. Le shedeh; étude d’un procédé de vinification en Égypte ancienne. BIFAO 1995;95:459-92.

[4] For example, the Harris Papyrus 500 mentions the bitterness of a lover due to the absence of the beloved: “The sweet shedeh, in my mouth, is like the bile of birds.”

[5] Columella, De l’agriculture, Les arbres XII, 19.

[6] Pliny, Natural History, XVI, 11, 80.

[7] Maria Rosa Guasch-Jané, Cristina Andrés-Lacueva, Olga Jáuregui, Rosa M. Lamuela-Raventós, The origin of the ancient Egyptian drink Shedeh revealed using LC/MS/MS, Journal of Archaeological Science, Volume 33, Issue 1, 2006, Pages 98-101, ISSN 0305-4403.

Other articles in English from the Nunc est bibendum blog