Translated from french with Deepl (please notify us of errors)

You don’t play with food. But in the Greek world, around the 5th century BC, this modern rule of etiquette did not apply. Imagine: at the end of a banquet, the guests, having drunk as much as philosophised, engage in a game of skill. In turn, with a deft flick of the wrist, they spin their wine glasses to throw the residual lees towards a target placed in the centre of the room. The first to hit the target wins cakes and sweets or, better still, the omen of success in love.

This game is Kottabos (κόττταϐος), as old as the word that designates it, whose pre-Greek etymology is obscure. The practice is thought to have originated in the Greek colonies of Sicily, but is also known to the Etruscans. It then spread throughout the Greek world and became very popular in Athens. Numerous authors mention it, including Alcalaeus of Mytilene, Anacreon, Pindar, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes. In the Hellenistic and Roman periods, authors still mention it, although the game fell out of fashion a few centuries ago.

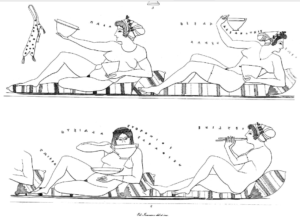

The game of Kottabos is also depicted on the banquet scene in the so-called ‘Diver’s Tomb’ in Paestum, a Greek colony on the Tyrrhenian coast, as well as on red-figure vases. The player is shown reclining, holding his cup (usually a kylix) by a handle with his fingertips. The poet Antiphanes gives a precise description of the gesture:

B: “So show me how to take this vase.”

A: “You must spread your fingers and bend them a little, as if playing the flute; you must pour wine into the vase, but very little.”[1]

A hijacked libation

The game doesn’t just spill wine, it disrupts rites, particularly that of libation. At banquets, the libation marks the end of the meal (δεῖπνον / deĩpnon) and the beginning of the drinking (πότος / pótos). It consists of offering a few drops of pure wine to a deity to elicit his benevolence.

Kottabos, on the other hand, comes when the hour is late. And it is the residue of the wine, not the most pleasant to drink, that is sacrificed for profane and often erotic purposes… At a time of the evening when only the most resistant are still capable of skill. Moreover, over time, the verb kottabízô (κοτταϐίζω), “to play Kottabos”, will gradually take on the imagined meaning of vomiting. One projection represents another.

But what are the rules of this end-of-drunken-party game? They are innumerable and vary according to time and place. What they all have in common is that there is a target. You have to hit it to win. Sometimes it’s a simple cup. Other times it’s small saucers (ὀξυϐάφα / oxybápha) floating in a container filled with water, which you have to sink. In the most sophisticated variant, a small disc (πλάστιγξ / plástinx) was perched on a bronze lamppost; as it fell onto a statue or tray, halfway up or at the foot of the lamppost, it made a bell-like sound announcing victory.

Before making the shot, the player would make a dedication to a loved one, or stake his or her chance of success in love. The result of the throw gave a good or bad omen. This can be seen on a psykter[2] from the workshop of the famous Athenian potter Euphronios towards the end of the 6th century BC[3]. It shows four hetaera – today we would say escort-girls – playing Kottabos. One of them, Smicra, punctuates her shot with “I’ll play this one for you, Leagros”, the latter character being an archetypal Athenian golden youth of the time, often cited on the vases.

Women playing?

As the Athens of the time may have been the cradle of democracy, but not the cradle of gender equality, specialists do not take the depiction of women playing Kottabos literally. It could be a mockery.

Two clues support this theory. The inscriptions are not in the Greek spoken in Athens, but in Doric dialect, spoken in particular in Sparta, the eternal enemy of Athens. The women are lying on simple mats rather than divans, which also fits the stereotype of Spartan roughness. Seen from Athens, these women drinking and gambling could only be representatives of a people who were not really civilised.

[1] Antiphanes, preserved by Athenaeus, Deipnosophists, Book XV, 667: ᾯ δεῖ λαβὼν τὸ ποτήριον δεῖξον νόμῳ. Αὐλητικῶς δεῖ καρκινοῦν τοὺς δακτύλους οἶνόν τε μικρὸν ἐγχέαι καὶ μὴ πολύν.

[2] This is a ceramic vase used to cool wine. The psykter, filled with wine, was placed inside a crater with cold water.

[3] classical art research centre, 200078, Athenian, St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum.

Pour en savoir plus

- Sparkes, Brian A. (1960). Kottabos: An Athenian After-Dinner Game. Archaeology. 13: 202–207 – via JSTOR.

- Pascale Jacquet-Rimassa, Κοτταβος. Recherches iconographiques. Céramique italiote. 440-300 av. J.-C., Pallas. Revue d’études antiques, année 1995, 42 pp. 129-170.

- Wikipedia article on Kottabos.

March 2024, reproduction prohibited

Other articles in English from the Nunc est bibendum blog