From daily bread hastily shared to banquets where wealth and connections are displayed, the Roman table constantly oscillates between moral restraint and acknowledged pleasure. Eating in Rome never amounts to mere necessity: each meal involves codes, hierarchies, and values, revealing a society where the art of living is thought through as much as it is savored.

Daily meals

The ientaculum, taken in the morning, and the prandium, a light midday meal, respond to individual needs and belong to the time of negotium (work), that of professional, civic, or military activities. The cena, on the other hand, constitutes the main meal when it takes place: served in the evening, it belongs to the time of otium (leisure) and readily takes on a collective and social dimension.

This model, however, is not that of all Romans. Soldiers on duty, workers subject to time constraints, as well as a large portion of the modest populations could hardly participate in an elaborate cena; for them, the prandium might constitute the only real meal of the day. Finally, in certain normative situations, particularly mourning, sources indicate that one limited oneself to a single daytime meal.

The ientaculum is a very brief morning meal, taken upon rising. It most often consists of bread, sometimes rubbed with garlic, accompanied by cheese and water. Depending on social status, it could be enriched: in well-to-do circles, one also found eggs, honey, milk, and fruit. Bread could also be consumed with olives, olive oil, or, more occasionally, with wine mixed with water.

In the most affluent circles, it had become customary to concentrate professional, political, and social obligations in the morning.

The prandium is a midday meal, sober and quickly taken, often without real staging, sometimes even standing. Frugal by nature, it consisted of cheese, fruit, some vegetables, porridge, or bread dipped in wine, with water or diluted wine serving as a beverage. It did not exclude, on occasion, hot dishes, frequently consisting of leftovers from the day before.

The cena and the convivium

After the prandium, the elites devoted the rest of the day to final current affairs, then went to the baths, an essential preparatory step for the evening meal. Around the eighth or ninth hour (depending on the variable length of the day according to the season), the cena began and could extend until nightfall, or even well beyond when the meal took the form of a true banquet.

The invitation to share a meal constitutes an essential element of Roman social rules. Not inviting an acquaintance could be perceived as a lack of consideration, just as neglecting to return a received invitation. The invitation was not necessarily formalized in writing: it could be verbal and made informally, particularly on the occasion of a meeting at the baths.

Frequenting the baths, which often marks the first stage of daily otium, responds to several complementary functions. It first satisfies a hygienic imperative, cleanliness being a sign of civilization. It then responds to a medical logic: the bath is supposed to promote the evacuation of humors and prepare the body for the intake of food. Finally, going to the baths has a major social dimension: it is a place where one shows oneself, where one maintains one’s relationships, and where one asserts one’s rank in society.

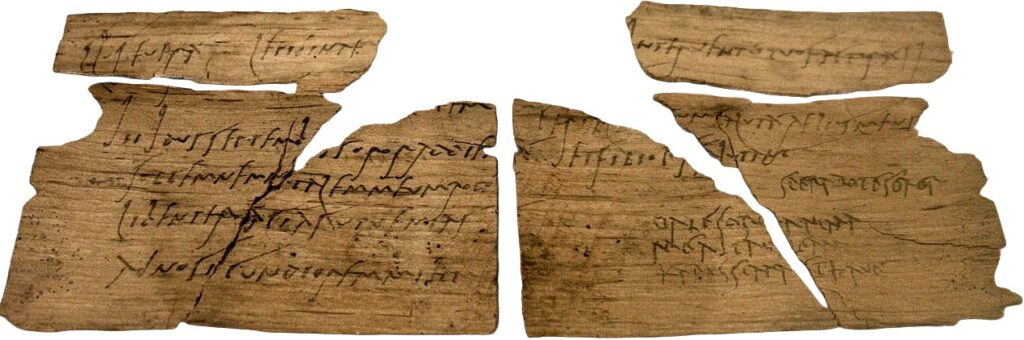

Dinner invitations could also take a written form. Archaeological excavations have thus brought to light, at Vindolanda (Roman Britain), a wooden tablet containing an invitation addressed by Claudia Severa, wife of an officer, to her friend Sulpicia Lepidina, inviting her to celebrate her birthday in the company of her husband[1]. This exceptional document attests to the existence of written sociability, even in a provincial military context.

Literary sources confirm the importance given to these customs. Pliny the Younger reports, in one of his letters[2], that accepting an invitation and then not showing up is felt as a true affront, a sign of a serious breach of the rules of civility. While the figure of the self-interested guest, the parasitus, always ready to take advantage of others’ meals, is well known to Romans and often mocked by satirists, it seems socially acceptable, in certain contexts, for a guest to present himself accompanied, provided that hierarchies and customs are respected.

The meal is generally taken in a specially arranged room, the triclinium, which takes its name from the three banquet couches (lecti) arranged in a U around the table. Guests recline there to eat, each couch being able to accommodate several people, while the fourth side remains free to allow service.

When the number of guests exceeds the capacity of one triclinium, one can install several sets of couches, either in a single sufficiently large room or in several distinct halls. Some residences are thus designed to accommodate several triclinia. Literary sources also attest to this practice: Cicero reports that when he receives Caesar accompanied by his retinue, the guests are distributed in three rooms, one reserved for Caesar and his close circle, the others accommodating the rest of the entourage, particularly freedmen[3].

Archaeological data also show the existence of dining rooms arranged outside the house, particularly in gardens or peristyles. Pliny the Younger thus describes a summer dining room (triclinium aestivum), designed to enjoy freshness, light, and landscape, illustrating the adaptation of the meal space to the seasons and the natural setting[4].

From the late imperial period onward, one observes in parallel an evolution of furniture and guest arrangement: the semicircular bench, the stibadium, tends progressively to replace the classic three-couch triclinium. This new configuration, more encompassing and better adapted to large banquets, spreads widely from the 2nd-3rd century CE, without however immediately eliminating older forms.

The guest does not recline to eat dressed in his ordinary clothes. Upon arrival, he removes his toga and, if he has not brought it himself, receives a lighter and more comfortable outfit, the synthesis, specifically intended for the meal. He also removes his shoes, and his feet are washed, according to a custom attested by both literary sources and iconography.

It is furthermore customary for the guest to bring a napkin (mappa), which he spreads on the cushions to avoid staining them. This napkin can also serve, if the host authorizes it, to take away leftovers from the meal at the end of the feast, a socially accepted practice. Satirical authors, however, delight in mocking those who abuse this tolerance: Martial thus mocks the glutton Santra, who fills his mappa and even goes so far as to resell his booty[5].

It is socially delicate for the host to send away someone who presents himself without having been invited, as the rules of civility impose a certain tolerance. Satirical authors, however, delight in mocking those who abuse this custom: these unwanted guests, called umbrae (“shadows”), take advantage of meals to which they have not been invited.

The course of the meal

The Latin expression ab ovo usque ad mala (“from egg to apples”) designates a complete dinner, from beginning to end. A multi-course meal opened with the gustatio, composed of light dishes—eggs, vegetables, or salads—to which could be added ingredients reputed to facilitate digestion.

The cena proper constituted the heart of the meal and gave a large place to meat or fish dishes, in symbolic continuity with communal banquets derived from sacrifices. The dinner ended with the secundae mensae, composed of fruit, nuts, or sweets belonging more to pleasure than to necessity.

Roman literature dwells mainly on the dietary practices of the upper classes. The most famous description of a Roman meal undoubtedly remains Trimalchio’s dinner in Petronius’s Satyricon[6], a deliberately caricatural extravagance, which could not be considered representative, even of the wealthiest elites.

Martial, on the other hand, offers the image of a more credible dinner. He describes a meal beginning with a gustatio composed of simple but varied dishes—mallow leaves, lettuce, chopped leeks, mint, arugula, mackerel with rue, sliced eggs, and marinated sow’s udder. The main course combines pieces of kid, beans, green vegetables, chicken, and cold ham, before ending with fresh fruit and quality wine[7].

Table manners and the place of women

One most often eats with one’s fingers, with the right hand, limiting contact to the first phalanges. Slaves assist the guests to ensure their comfort and regularly offer them something to wash their hands. It should be remembered that foods are generally pre-cut in the kitchen, even if they may be brought whole before the diners for presentation reasons.

The guest can also use small plates, held in the left hand, as well as spoons (ligulae or trullae). The use of toothed utensils, comparable to forks, is attested in a punctual manner, according to the nature and consistency of the dishes, without constituting a general norm.

Leftovers and food waste are often thrown on the ground during the meal. They must not be picked up immediately: according to an attested belief, they then belong to the world of the dead, the souls of the deceased being supposed to circulate in the house; touching them during the cena would be sacrilegious. The floor is cleaned only once the meal is finished.

This custom finds an echo in decorative art: certain mosaics deliberately represent a floor strewn with food remains (asarotos oikos), a fixed image of a completed banquet, which allows one to symbolically evoke the custom without retaining its material inconveniences.

Unlike classical Greek customs, women have their place in the Roman banquet. At the end of the Republic, and undoubtedly earlier in certain circles, they dine with men, recline on banquet couches, and consume wine, even if this practice remains criticized and socially regulated. On certain occasions, children can also be present, in order to be initiated into the codes of sociability and behavior in society.

In the most ancient periods, however, women often seem to be admitted only seated on stools, near the triclinia—like children or slaves. Testimonies indicate that in the imperial period, on the other hand, they fully participate in the banquet and take their place among the guests. This evolution is confirmed by archaeological and epigraphic sources: in the “House of the Moralist” in Pompeii, an inscription explicitly exhorts male guests to restraint in their remarks and behavior toward the women present[8], a sign of a now recognized and regulated mixed-gender practice.

Multi-course meals are provided by the house’s slaves. Their role appears particularly visible in the art of Late Antiquity, where they are frequently represented as figures of domestic hospitality and markers of aristocratic luxury.

One will also note the difference with the Greek banquet, where the times of the meal (deipnon) and those of drinking (symposion) are clearly distinct. In Rome, wine is consumed throughout the meal, even if the commissatio marks a moment when drinking takes a predominant place.

The difference is also institutional: the Greek banquet is a civic and public act, reserved for citizens, while the Roman banquet remains a private act, the convivium, inscribed in the domestic and family sphere.

The diet of the poor and commercial catering

The majority of Rome’s inhabitants lived in collective buildings (insulae) generally lacking true kitchens. Some shared cooking installations could exist in the common spaces of the ground floor, but most dwellings made do with a charcoal-fired brazier for rudimentary cooking. Often insufficient ventilation and high fire risks help explain the essential role of out-of-home dining in the daily diet of modest populations.

Excavations at Pompeii have uncovered 158 catering establishments, of which about 55% are located near crossroads, revealing a strategic location in urban space. These shops, inns, and taverns (tabernae, cauponae, popinae) offered prepared or ready-to-eat foods.

Recognizable by their masonry counter pierced with cavities intended to receive amphorae or jars (dolia), certain establishments had a heating device allowing them to keep dishes warm, while others limited themselves to the conservation and distribution of food. Commercial mills and ovens, most often combined within bakery complexes, completed this infrastructure essential to urban food supply.

The social status of these places was profoundly ambiguous. Mainly frequented by the popular classes and associated, in moral discourse, with a despised clientele (slaves, sailors, pimps) as well as with drunkenness and prostitution, they nonetheless attracted members of the elite.

In his scathing portrait of Vitellius, Suetonius thus reports that the future emperor, on his way to his command in Germany, readily stopped at inns, “laughing with muleteers and travelers.” Having become emperor, he continued to frequent “the popinae along the roads,” where he indulged in notorious gluttony, devouring “steaming dishes, even those from the day before and half-eaten”[9].

What truly scandalized aristocratic morality was not so much the frequenting of these places as the social mixing without respect for hierarchies. Paradoxically, the culinary quality of certain establishments was such that popina came to metaphorically designate culinary refinement itself. To denounce the culinary creativity of Apicius, the philosopher Seneca accuses him of having “professed the science of the popina“[10].

The health issue and medicine

Modern studies draw an overall satisfactory assessment regarding the quantity of food available in Rome. The caloric ration is generally satisfactory. There may have been shortages but not famines. The annona system, based on public grain supply, plays an essential role in this regard in limiting the risks of shortage.

Historians, however, emphasize the nutritional imbalances of this diet, as they appear through ancient texts and archaeological data. Deficiencies, particularly in vitamins A and D, are frequently mentioned. The study of skeletons uncovered at Herculaneum also reveals signs of anemia, indicating forms of malnutrition or undernutrition. While the poorest largely consume the same basic foods as the richest, they access them in smaller quantities and in less varied and less qualitative forms.

Ancient medicine is organized around three major domains: surgery, pharmacopoeia, and dietetics, the latter being considered the noblest and most fundamental of healing methods. Galen summarizes this primacy by affirming that food constitutes the first of remedies[11], a central principle of Hippocratic medicine that he takes up and systematizes.

Good health rests on the balance of the four humors (blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm) that govern the organism. The physician can therefore prescribe an adapted diet to restore the humoral balance altered by illness. According to age, sex, the patient’s constitution, or even the season, certain foods are recommended rather than others.

Celsus, for example, advises, in winter, favoring bread and boiled meats, foods judged more warming and easier to digest, while in summer he recommends more vegetables and roasted meats, considered more suitable for heat[12]. The digestion of food in the body is then conceived as a process analogous to the cooking of food in the kitchen.

Cultural values and food symbolism

The Roman situates himself between two normative poles: for himself, he must conform to an ideal, largely mythologized, of frugality and self-mastery; toward others, on the other hand, it is his duty to display the generosity and sumptuousness expected of the host. This tension between personal sobriety and social ostentation runs through all Roman moral discourse, from Cato the Elder to Seneca, and durably structures banquet practices.

From the imperial period onward, certain philosophical currents—particularly Stoics and Cynics—denounce the excesses of the table and value simple food, in accordance with nature (secundum naturam). Seneca thus makes dietary frugality a moral exercise, intended to test the individual’s inner freedom:

“What we need is either free or inexpensive: nature demands bread and water. No one is poor for this.“[13]

This moral criticism is taken up and amplified by Christian authors. For them, gluttony (gula) becomes a major vice, likely to turn man away from God. Fasting and dietary moderation are progressively elevated to the rank of spiritual practices: Tertullian makes it a religious discipline in its own right, Jerome associates dietary frugality with asceticism and chastity, while Augustine integrates fasting into a broader moral reflection on the mastery of desires[14].

At the same time, the economic and social transformations of Late Antiquity profoundly modify dietary practices. The decline of urban life in the West, the weakening of commercial networks, and the withdrawal of elites to their rural estates favor simpler food, based on local self-sufficiency. In this context, the urban lifestyle comes to be associated with decadence, while hunting and pastoral farming embody, in moral as well as Christian discourses, a renewed ideal of virtuous simplicity.

Brief bibliography

- André, Jacques. L’alimentation et la cuisine à Rome. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, coll. «Études anciennes», 1961 (rééd. ultérieures).

- Badel, Christophe. «La nourriture romaine au quotidien». In Histoire de l’alimentation. De la Préhistoire à nos jours, sous la dir. de Florent Quellier, p. 265–285. Paris : Belin, 2012.

- Tilloi-D’Ambrosi, Dimitri. L’Empire romain par le menu. Paris : Arkhê, 2017.

[1] Tab.Vindol. 291. Birthday Invitation of Sulpicia Lepidina.

[2] Pliny the Younger, Letters I, 15: Heus tu! Promittis ad cenam, nec venis? “What! You promise to come to dinner and you don’t come?”

[3] Cicero, Ad Atticum XIII, 52: praeterea tribus tricliniis accepti sunt περὶ αὐτὸν valde copiose. libertis minus lautis servisque nihil defuit. “In addition, they were received very generously in three triclinia around him [Caesar]. As for the freedmen, the service was less sumptuous, but the slaves lacked nothing.”

[4] Pliny the Younger, Letters 2.17.

[5] Martial, Epigrams VII, 20: Sed mappa cum iam mille rumpitur furtis, rosos tepenti spondylos sinu condit et deuorato capite turturem truncum (….) Haec per ducentas cum domum tulit scalas seque obserata clusit anxius cella gulosus ille, postero die vendit. “But when his napkin, already, threatens to burst under a thousand thefts, he conceals in his warm bosom rosy shellfish and, having devoured the head, the body of a turtledove. (…) After carrying all this home up two hundred steps, then locking himself, anxiously, in his well-secured cellar, this glutton resells the next day.”

[6] Petronius, Satyricon 26–78.

[8] Pompeii, Regio III, Insula 4, no. 2–3 (Casa del Moralista / Domus M. Epidius Hymenaeus). Painted inscription in the triclinium: CIL IV, 7698 = CLE 2054.

[9] Suetonius, Life of Vitellius, VII: per stabula ac deversoria mulionibus ac viatoribus praeter modum comis, ut mane singulos iamne iantassent sciscitaretur seque fecisse ructu quoque ostenderet, “in the stables and inns, excessively friendly with muleteers and travelers, to the point of asking each one in the morning whether he had breakfasted and showing with a belch that he had done so himself”; XIII: circaque viarum popinas fumantia obsonia, vel pridiana atque semesa, “and in the popinae along the roads, steaming dishes, even those from the day before and half-eaten.”

[10] Seneca, Consolatio ad Helviam, X, 8: …qui in ea urbe, ex qua aliquando philosophi velut corruptores iuventutis abire iussi sunt, scientiam popinae professus disciplina sua saeculum infecit, “…who, in that city from which philosophers had once been ordered to depart as corrupters of youth, professed the science of the popina and infected his age with his doctrine.”

[11] Galen, De alimentorum facultatibus, I; De sanitate tuenda, I.

[12] Celsus, De medicina I, 3.

[13] Seneca, Letters to Lucilius, 25, 4: Aut gratuitum est quo egemus, aut vile: panem et aquam natura desiderat. Nemo ad haec pauper est.

[14] Tertullian, De ieiunio adversus psychicos / Jerome, Epistulae 22 (Ad Eustochium) and 52 (Ad Nepotianum) / Augustine, Confessiones X, 31–32.