Translated from french (please notify us of errors)

Rome destroyed Carthage, but not the entirety of its legacy. It is to Mago, a Punic agronomist from the 3rd century BCE, that we owe the most precise description of the art of making a sweet wine highly prized during Antiquity: passum[1]. Admittedly, Hesiod, in his Works and Days (609-614), already mentions the technique of raisin wine, and Homer might allude to on-vine desiccation in the Odyssey (VII, 123-125), but it is in Africa that passum finds its most sophisticated codification.

Mago’s text has vanished, but the Roman agronomist Columella, in the 1st century, draws extensively from his predecessor’s source. “Mago prescribes making excellent passum thus, as I have done myself.”[2]

Columella faithfully reports the Carthaginian method: “Pick well-ripened clusters of early grapes; reject dried or spoiled berries.” Only perfect grapes deserve to become passum.

What follows reveals genuine drying engineering: raised hurdles at four-foot intervals, nocturnal protection against dew, optimised air circulation. But Mago’s expertise doesn’t stop there. Once the grapes are dried, a subtle operation begins: the berries are rehydrated with the finest possible must. For six days, they absorb this fresh juice. Once swollen, they are placed in baskets and pressed to yield first-quality passum.

Roman Refinement

The Romans perfected the Carthaginian technique, developing an entire arsenal of variants. Columella proposes an even more sophisticated method for Apiana grapes -Roman muscat: suspension of whole clusters, stratification in layers moistened with old wine, extraction in stages to create complexity impossible to achieve otherwise.

Nothing is wasted. After the first pressing, the pomace undergoes a second treatment: mixed with fresh must, trodden, pressed and fermented for twenty to thirty days. This second extraction produces passum secundarium, of lesser quality, but revealing of an almost industrial approach.

Columella recounts that some producers still find ways to recover a third product from the same grapes: “Some people age rainwater for this purpose, and boil it until reduced by half. When they have dried their grapes as I have explained, they use this water instead of wine, and complete the operation as above. This process, when one has plenty of wood, costs very little, and this wine is even, for use, sweeter to the taste than those prepared according to previous methods.”[3]

Passum‘s success in the Roman world was considerable. Pliny the Elder establishes a precise geographical hierarchy: “After Cretan wine, that of Cilicia and Africa is esteemed.”[4] Each terroir develops its signature, creating a veritable map of Mediterranean flavours.

The historical persistence of the phenomenon is impressive: according to David L. Thurmond[5], specialist in ancient viticulture, Cilician passum “still enjoyed great renown in the mid-10th century” -over thirteen centuries of continuity! This longevity is explained by the product’s remarkable adaptability: one even finds a “kosher form exported to Roman Palestine for Passover”.

Thus, passum was not uniform. An entire range of variations existed according to Pliny[6]: amber Psithium, dark Melampsithium, Galatian Scybelite with mulsum taste, Sicilian Haluntium… Diachyton represents a particular innovation: grapes dried “in an enclosed place for seven days on hurdles seven feet from the ground, sheltered from dew”»[7], to obtain “a wine of excellent taste and smell”.

Cretan Counterfeit

Beyond ancient texts, modern archaeology sheds new light on this ancient production. Conor Trainor, a researcher at the University of Warwick, has conducted excavations at Knossos for ten years that reveal a more complex reality than agronomic treatises suggest[8]. His discovery of terracotta beehives associated with wine installations indicates that some Cretan producers added honey to ordinary wine to imitate the sweetness of true passum.

This ancient “counterfeiting” illustrates the eternal tensions between artisanal quality and commercial demand. Faced with exploding Roman demand, some vintners prioritise profitability over authenticity. The massive quantities of Cretan wine imported to Rome suggest that Roman consumers were less concerned with authenticity than we might be.

Today, the tradition of raisin wine endures in Amarone della Valpolicella, the straw wines of the Jura, Recioto from Veneto, or Passum de Mago, a modern Tunisian wine produced in the Kelibia region—ancient agricultural heart of Carthage. In modern Tuscany, grapes are left to wither for over a month, until early December, reproducing exactly the ancient timings. This technique of concentrating sugars through natural berry dehydration, either on the vine or off the stock on hurdles or suspended, today bears the name passerillage, recalling in its root the ancient passum.

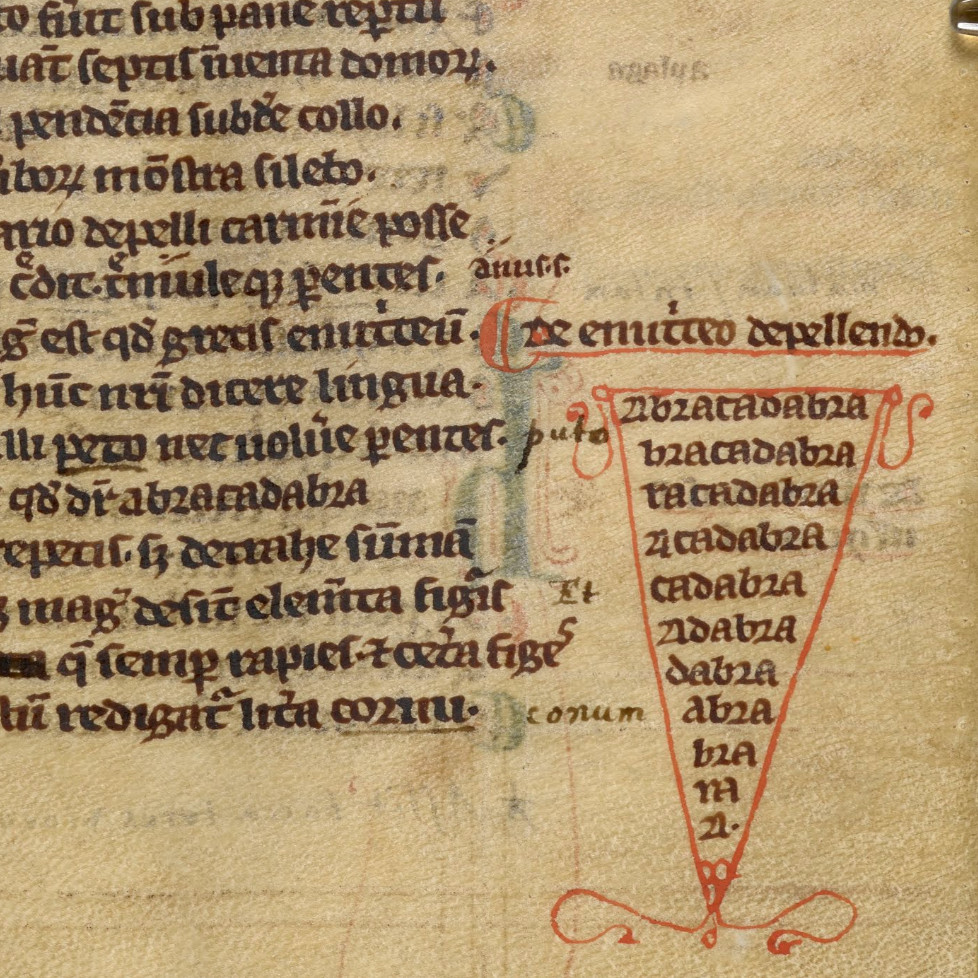

[1] The term passum derives from the Latin verb pandere (to spread, to deploy), whose past participle passum literally means “that which has been spread”. This etymology reveals the very essence of the technique: grapes are spread in the sun to concentrate their sugars. Columella indeed uses this exact verb in his description: in sole pandere uvas.

[2] Columella, De re rustica 12.39.1: Passum optimum sic fieri Mago praecipit, ut et ipse feci. Uvam praecoquem bene maturam legere, acina mucida aut vitiosa reiicere; furcas, vel palos, qui cannas sustineant, inter quaternos pedes figere, et perticis iugare: tum insuper cannas ponere, et in sole pandere uvas, et noctibus tegere, ne irrorentur. Quum deinde exaruerint, acina decerpere, et in dolium aut in seriam coniicere, eodem mustum quam optimum, sic ut grana summersa sint, adiicere : conbiberint uvae, seque impleverit, sexto die in fiscellam conferre et prelo premere, passumque tollere.

[3] Columella, De re rustica 12.39.4: Quidam aquam caelestem veterem ad hunc usum praeparant, et ad tertias decoquunt. Deinde quum sic uvas, ut supra scriptum est, passas fecerunt, decoctam aquam pro vino adiiciunt, et cetera similiter administrant. Hoc, ubi lignorum copia est, vilissime constat, et est in usu vel dulcius, quam superiores notae passi.

[4] Pliny, Natural History 14.81: Passum a Cretico Cilicium probatur et Africum. et in Italia finitimisque provinciis fieri certum est ex uva quam Graeci psithiam vocant, nos apianam, item scripulam, diutius uvis in vite sole adustis aut ferventi oleo. quidam ex quacumque dulci, dum praecocta, alba, faciunt siccantes sole, donec paulo amplius dimidium pondus supersit, tunsasque leniter exprimunt.

[5] David L. Thurmond, From Vines to Wines in Classical Rome, Leiden & London, 2017, p. 49, 196, 230.

[6] Pliny, Natural History 14.80: Vinum omne dulce minus odoratum; quo tenuius, eo odoratius. colores vinis quattuor: albus, fulvus, sanguineus, niger. psithium et melampsithium passi genera sunt suo sapore, non vini, Scybelites vero mulsi, in Galatia nascens, et Haluntium in Sicilia. nam siraeum, quod alii hepsema, nostri sapam appellant, ingeni, non naturae, opus est musto usque ad tertiam mensurae decocto. quod ubi factum ad dimidiam est, defrutum cr. omnia in adulterium mellis excogitata, sed priora uva terraque constant.

[7] Pliny, Natural History 14.84: Medium inter dulcia vinumque est quod Graeci aigleucos vocant, hoc est semper mustum. id evenit cura, quoniam fervere prohibetur -sic appellant musti in vina transitum-; ergo mergunt e lacu protinus aqua cados, donec bruma transeat et consuetudo fiat algendi. est etiamnum aliud genus per se, quod vocat dulce Narbonensis provincia et in ea maxime Voconti. adservatur eius gratia uva diutius in vite pediculo intorto.

[8] Conor Trainor, How I uncovered a potential ancient Rome wine scam, The Conversation, june 2025.

Other articles in English from the Nunc est bibendum blog