Translated from french (please notify us of errors)

It is one of the iconic objects of Antiquity. The amphora still covers part of the Mediterranean seabed today, serves as a tourist trap in souvenir shops and carries with it a whole mythology specific to these ancient objects now vanished. Well, not quite! The amphora has made a notable comeback for just over a decade in wine preservation. A use that was one of the most widespread in ancient Rome.

Before becoming Roman, the amphora (etymologically: that which is carried from both sides, equipped with two Ahandles) is Middle Eastern. In lands where deserts are more numerous than forests, being able to manufacture containers from clay was essential. Then, the amphora passed through Greece and became a Roman star around the 3rd century BCE. It was produced by the tens of millions each year. It was used to transport oil, to supply the legions with wine, but could also contain dried fruit, fish in brine or the famous garum.

Mountain of rubbish

This very common object tells the story of both everyday Roman life and the globalisation subsequently carried out by the Empire, as traces of it can be found as far as Asia.

From everyday object to rubbish, it is but a short step. Whilst the amphora is a preservation object, it is, for its part, hardly preserved after use. The Testaccio Hill in Rome, made famous by Pasolini through his film Accattone, is in reality a mound of waste composed of the remains of 50 million amphorae.[1]

More romantic and just as revealing of the importance of amphorae, especially when full of wine, is this delightful quotation from Martial:

“The beautiful Phyllis had, throughout an entire night, lavished upon me generously favours of every kind. As I was thinking, in the morning, of giving her either a pound of perfumes from Cosinus or Niceros, or a good quantity of Baetican wool, or finally ten gold coins struck with Caesar’s seal, Phyllis throws her arms around my neck, presses upon my mouth a kiss as long as that of amorous doves, and begins to ask me for an amphora of wine.”[2]

Frozen wine

But the amphora had to face a dangerous rival: the barrel which, contrary to a fairly widespread idea, is not Gallic. Its origin dates back to approximately five centuries before our era. Two regions dispute its paternity. On one side, Rhaetia, situated between the Austrian Tyrol, the Grisons and the Italian Friuli up to Verona. It is very likely from this region that Pliny the Elder describes in his Natural History, when he speaks of wine stored “in wooden vessels bound with hoops” in the Alpine regions. Pliny’s description is, moreover, worth its weight in grapes:

“There are, once the wine has already been harvested, great differences depending on the climate. Around the Alps, they preserve it in wooden vessels, which they surround with coverings, and, during freezing winters, they ward off the frost with fires. A rare thing to say, but sometimes observed: the barrels burst and masses of frozen wine form, a prodigious phenomenon, since the nature of wine is not to freeze; ordinarily, it merely becomes sluggish in the cold.”[3]

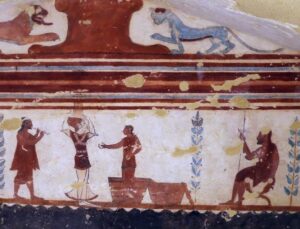

Further south and less Alpine, Etruria, that is to say present-day Tuscany, part of Umbria and Emilia-Romagna, constitutes the other region claiming its barrel-making primacy. Moreover, the technique of assembling staves for vats was indeed also known to the Etruscans as attested by certain tomb paintings which unambiguously present hooped wine vats, notably that of the Tomb of the Jugglers at Tarquinia. The two regions are, furthermore, quite close.

It is therefore more than plausible that barrels and amphorae coexisted for several centuries, in the company of a third actor: the dolia. These immense earthenware jars were placed in ships somewhat in the manner of containers transported today on super-tankers. It is, moreover, probably the dolia-barrel alliance that brought an end to the glorious era of amphorae. The historian and archaeologist André Tchernia provides us with an example: “Wine brought in dolia from Campania or Tarraconensis went up the Rhône as far as Lyon, where it was transferred into barrels. Other boats then loaded them to take them up the Saône, then the barrels of wine crossed on carts through the Langres plateau as far as the Rhine.”[4]

For centuries, however, the amphora resisted. As Sarah Rey, senior lecturer at the Polytechnique Hauts-de-France University, points out, the amphora even survived the Roman Empire, as traces of it dating from the 8th century can be found.[5]

Too heavy compared to the barrel, too small compared to the dolium, the amphora gradually disappeared from major commercial circuits. Then the barrel became the symbol of wine transport and preservation.

It still is in many respects. But somewhat like farro which, during Antiquity, was supplanted by wheat and which is once again on our tables, the amphora is resurfacing and is much more than an attraction for underwater diving. On the one hand, its preservation qualities are real, promoting excellent oxygenation of the wine. On the other hand, clay, unlike wood, is a neutral material: it does not alter the original taste of the wine with oakiness. The amphora is therefore particularly suited to ‘natural’ wines where one seeks above all to exalt the taste of the fruit.

Be that as it may, today’s winemakers are undoubtedly inspired as much by Roman amphorae as by Georgian kvevri. Used continuously for millennia in Georgia for the fermentation and preservation of wine, resembling dolia more than amphorae, they are much older than the oldest Mediterranean amphorae: traces of them have been found dating back to 6000 BCE.[6]

[1] Monte Testaccio article on Wikipedia.

[2] Martial, Epigrams, Book 12 – LXV: Formonsa Phyllis nocte cum mihi tota se praestitisset omnibus modis largam, et cogitarem mane quod darem munus, utrumne Cosmi, Nicerotis an libram, an Baeticarum pondus acre lanarum, an de moneta Caesaris decem flavos: amplexa collum basioque tam longo blandita quam sunt nuptiae columbarum, rogare coepit Phyllis amphoram vini.

[3] Pliny the Elder, Natural History, XXVII, 132: Magna et collecto iam vino differentia in caelo. circa Alpes ligneis vasis condunt tectisque cingunt atque etiam hieme gelida ignibus rigorem arcent. rarum dictu, sed aliquando visum, ruptis vasis sterere glaciatae moles, prodigii modo, quoniam vini natura non gelascit; alias ad frigus stupet tantum.

[4] André Tchernia, Rome et le vin: l’amphore, le tonneau et les dolia, in L’Histoire, décembre 2022

[5] Sarah Rey, «Pourquoi faire l’histoire de l’amphore?», présentation du magazine Faire l’histoire «L’amphore, un standard commercial antique», diffusé sur Arte samedi 20 novembre 2021.

[6] Kvevri article on Wikipedia.

Version du 12.11.2025, première version 20.2.2023

Other articles in English from the Nunc est bibendum blog