Translated from French (please notify us of errors)

At the heart of the ancient Mediterranean world, between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE, the Greeks developed an art of living through food that still resonates in contemporary dishes. Far from the stereotypical image of a generalized Spartan austerity, classical Greek cuisine reveals an unsuspected complexity, the result of a capricious geography and profound thought about humanity’s place in the cosmos.

“Where wheat, vine and olive grow”[1]

With these words young Athenian ephebes defined their homeland at the end of their military training. This triad, much more than a simple enumeration of agricultural products, constituted the very identity of Greek civilization. Bread, olive oil and wine were not mere commodities, but manifestations of a technè (τέχνη), that art which distinguishes civilized man from the barbarian. Each of the three elements requires work, a transformation of raw nature, and enjoys the protection of a major deity: Demeter for cereals, Athena for the olive, Dionysus for the vine. Hermes, protector of flocks, did not have their stature.

Diet defined not only habits, but an identity: eating bread, drinking mixed wine, using olive oil meant recognizing oneself as Greek, as opposed to Barbarians, perceived as milk drinkers, meat eaters or consumers of unmixed wine.

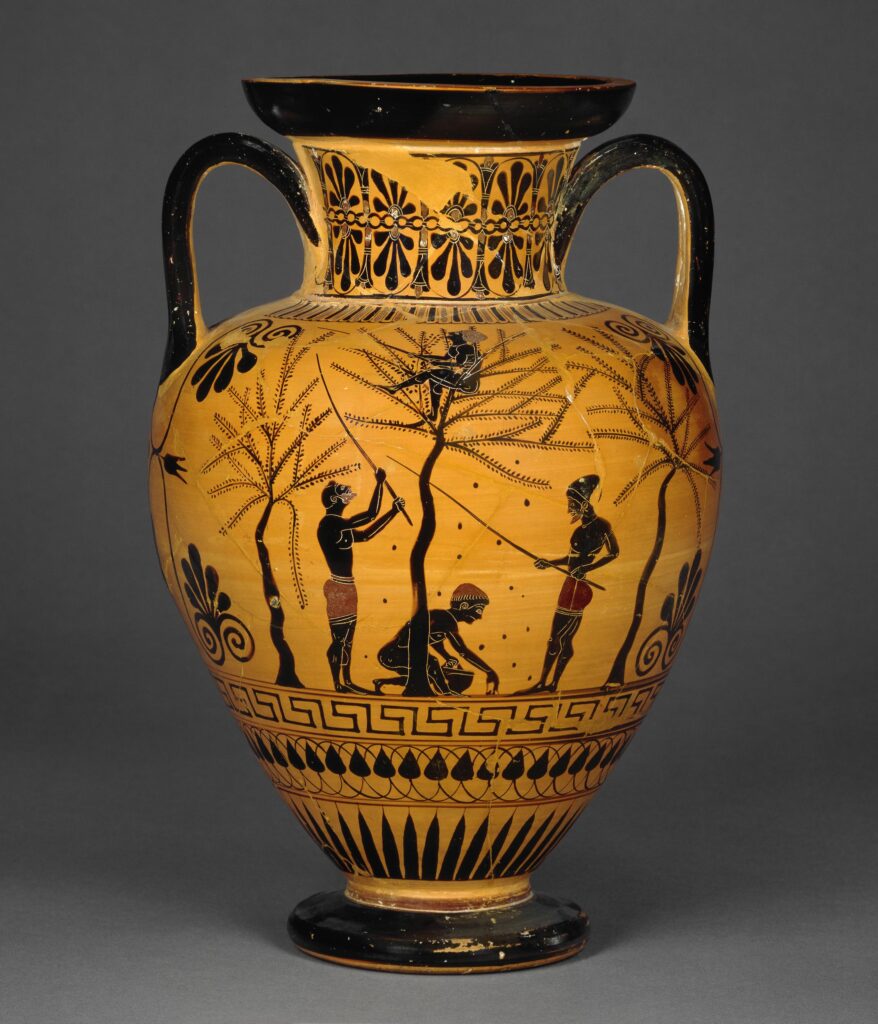

The olive tree, gift of Athena

The olive tree embodied Greek permanence itself. In Athens, legend had it that Athena planted it on the Acropolis, thus winning against Poseidon the right to become the city’s eponymous deity[2]. A tree of exceptional longevity, capable of regenerating through its shoots, the olive could live several centuries. However, it only began to produce after a long wait, around fifteen years, and only reached full maturity after several decades. Olive cultivation was patient work: the land was plowed twice a year, fertilized, the trees regularly maintained and pruned every seven or eight years. In reward, oil flowed in torrents – or almost.

The winners of the Panathenaea, the great civic festival of Athens, received amphorae filled with oil from the sacred olive trees: 140 amphorae for the first in the chariot race, each containing about forty liters, or some 5,600 liters in total, in other words a considerable fortune[3].

But oil was not only used for food. It permeated all aspects of Greek life: gymnastics, medicine, perfumery, lighting, crafts. Athletes rubbed their bodies with it before exercise, then scraped off with the strigil or stlegis (στλεγγίς) this mixture of oil, sweat and dust that gymnasium managers resold as a remedy against rheumatism[4]. In lamps, it modestly lit houses. In sanctuaries, it lubricated the ivory of chryselephantine statues. Even the pits mixed with dried pulp, the pomace, served as fuel for potters.

Eaters of sitos

Cereals constituted the very heart of the diet. The Greeks defined themselves as “eaters of sitos” (σῑτοφάγοι), a generic term designating all cereal preparations (sitos – σῖτος). One choenix per day – about 900 grams –, that was the worker’s ration. Double for barley, less nutritious. But speaking only of bread would be misleading: the Greeks consumed their cereals in multiple forms. The maza (μᾶζα), kneaded barley cake, rivaled leavened wheat bread baked in the oven. Hesiod already evoked this dream of the peasant exhausted by the heat:

“May I have the shade of a rock, wine from Byblos, a well-risen cake and goats’ milk, with the flesh of a heifer or lambs.”[5]

More than one food among others, sitos constituted the true foundation of food security: as long as cereal reserves were assured, accompaniments could vary, diminish or substitute without calling into question the vital balance.

Mixed wine, a moral norm

Wine, the third pillar of the triad, was the beverage par excellence. Homer already mentioned Pramnian, the wines of Pedasos, of Arnè[6]. In the Odyssey, Odysseus arms himself with wine from Ismaros to intoxicate the Cyclops Polyphemus[7]. In the classical period, each region had its vintages: the whites of Chios, the full-bodied wines of Santorini, the reds of Attica. But one never drank pure wine – that was considered barbaric. The ritual of the symposion (συμπόσιον) required mixing it with water, often in proportions of one-third wine to two-thirds water, perfumed with aromatics, resin, sometimes honey.

Wine mixed with water was not just a convivial custom: it embodied a moral norm, that of measure and self-control, while wine drunk pure became the sign of a dangerous otherness, of barbaric or tyrannical intoxication.

Access to quality water was not, however, taken for granted: private cisterns, public fountains and rainwater collection traced a social geography of water, closely monitored by cities and revealing urban inequalities.

Daily fare

The Greek food day was organized into several stages. In the morning, the akratisma (ἀκράτισμα), frugal, most often limited itself to bread dipped in wine. The midday meal, the ariston (ἄριστον), often amounted to little. Aristophanes evoked its simplicity with nostalgia in the Assembly of Women:

“Each came, bringing in a goatskin something to drink, with a crust of dry bread, two onions and three or four olives.”[8]

The deipnon (δεῖπνον), evening meal, constituted the main moment of the day. People sat on benches or stools – only the rich had dining couches. Sitos reigned at the center: bread, maza, or cereal porridge. Around it gravitated the opsa (pl. of ὄψον), these accompaniments – vegetables, cheeses, fish, meats – consumed in daily life.

This apparent balance concealed, however, a structural fragility: for a large part of the population, famine was not an exceptional event but a permanent risk, inscribed in dependence on harvests, trade and climatic variations.

Meat, so strongly associated with sacrifice, was not absent from ordinary diet. Recent archaeozoological excavations upset the image of a Greece vegetarian by necessity. At Tiryns, at Pylos, bones testify to animals of fine size, in better health than in the Early Bronze Age or the Middle Ages. Pork dominated meat consumption, easy to raise, content with urban waste. The Athenians knew several terms to designate the animal according to its age: choiros (χοῖρος) for the piglet, delphax (δέλφαξ) for the young pig, hys (ὗς) or sys (σῦς) for the pig or sow. Sheep and goats provided more occasional meat, cattle remained exceptional, reserved for great religious occasions. Meat was salted for winter.

Fish, on the other hand, was prized by all. Athenian markets overflowed with it: soles, turbots, red mullets, tunas, moray eels. Archestratus of Gela, gastronome of the 4th century BCE, though proud of his Sicily, praised the fish of the Bosphorus and the sturgeons of Lake Maeotis[9]. Athenians were particularly fond of fried small fish, anchovies, sardines.

The art of flavors

The Greeks had a considerable aromatic palette. Thyme, oregano, mint, ruta, fennel grew profusely on the arid hills. But prestigious aromatics came from afar. Herodotus recounted these fabulous legends about “Arabia Felix” whence came incense, myrrh, cinnamon, cinnamomum[10]. He detailed with relish the dangers faced by gatherers, confronting bats and vultures, or having to collect ladanum, aromatic resin from cistus, in the fleece of he-goats.

Silphion (σίλφιον) reigned supreme over refined cuisines. This mysterious plant from Cyrenaica, now extinct, was worth its weight in gold. The Cyrenaeans had made their fortune from it and had engraved it on their coins. Archestratus made it intervene abundantly in his recipes. Aristophanes proposed in the Birds to serve small roasted fowl drizzled with cheese, silphion oil and vinegar[11]. Doctors vaunted its purgative virtues, cooks perfumed rays and noble fish with it. Archestratus himself recommended using it with discernment: ideal with ray, it was useless with mullet or sea bass which were sufficient unto themselves[12].

Salt was extracted from coastal salt marshes or imported. From it was drawn garos (γάρος), that fermented sauce of fish entrails which perfumed almost all dishes, ancestor of Roman garum. The Greeks also prepared brines (almè – ἅλμη) to preserve olives, cheeses, meats.

Between simplicity and ostentation

Greek diet varied considerably according to social classes and regions. Literary texts speak mainly of aristocratic tables, inventive, sensitive to fashions, to exotic products. But the people lived in another food temporality, that of tradition, of daily gesture, of modest sufficiency. Their diet remains largely in the shadows, having left neither recipe books nor account books.

The poor supplemented their ordinary fare with wild plants: mallow, asphodel, arum. Theophrastus devoted long developments to them, emphasizing their nutritive virtues[13]. Mallow leaves were cooked like our spinach, arum tubers were reduced to flour. But certain herbs were only consumed as a last resort: chickweed, corncockle, pellitory were “famine vegetables,” bitter, sometimes toxic, requiring long cooking.

On the opposite end, distinguished tables sought novelty. Athenaeus, much later, listed 72 different kinds of bread, of all shapes and flavors: with cheese, with poppy, with honey, with olive, with sesame. The Hippocratic treatise On Regimen analyzed their specific properties – laxative, warming, nourishing. Athenian pastry-making enjoyed a flattering reputation. The symposia of the rich ended in sweet nibbles: honey cakes, dried fruits, various delicacies.

The Greeks also thought about diet in terms of deviation: excess, lack of measure or rupture of dietary customs were the subject of moral, medical and mythological discourses, constantly recalling the central value of moderation.

The sacred dimension of the act of eating

For a Greek, eating was never a purely biological act. Food wove the bond between gods and men, between citizens themselves. Sacrifices punctuated civic life: cattle were immolated during the Panathenaea, pigs at the Thesmophoria of Demeter. Sacrificial meat was divided between the altar (fats and bones for the gods), the priests (choice pieces), and the people (the rest). This sharing embodied the social and cosmic order.

Collective meals held considerable political importance. The eranos (ἔρανος), collective meal where each brought their contribution, manifested equality among citizens. The prytaneion (πρυτανεῖον), meal offered by the city to distinguished guests, ambassadors, Olympic victors, expressed public generosity. The symposion, banquet among peers, bound the elites together. All these food rituals defined belonging to the civic community.

Some philosophers, it is true, advocated a more austere regime. The Pythagoreans excluded beans, even meat. The Cynics were content with mallow and asphodel, supposed foods of the Golden Age believed to suppress hunger and thirst. But these extremes remained minority. The majority of Greeks sought balance between the frugality imposed by geography and the legitimate pleasure of the table.

The legacy of a gastronomic civilization

Classical Greek cuisine has not only transmitted products or recipes. It has elaborated a way of thinking about the meal: a hierarchy of foods, a balance between frugality and pleasure, attention paid to gestures, contexts and social uses of food.

More than a cuisine of fixed recipes, Greek diet thus appears as a culture of adaptation, founded on the substitution of resources and constant adjustment between necessity, availability and hierarchy of foods.

This legacy did not end with the end of the classical Greek world. Rome received it, transformed and amplified it. The Roman cena, the central place of bread, oil and wine, the use of fermented sauces, the taste for aromatics, medical reflection on foods or the opposition between ordinary table and ostentatious table prolong intellectual and practical frameworks forged in Greece. Even when it diverges from it, Roman cuisine dialogues with this model.

Understanding the Greek table thus means illuminating the foundations of the Roman table. Behind the diversity of dishes and tastes, the same conviction remains: eating is never a neutral gesture, but a social, cultural and symbolic practice.

Sources

- Janick Auberger, Manger en Grèce classique. La nourriture, ses plaisirs et ses contraintes, Québec, Presses de l’Université Laval, 2010.

- Jean-Manuel Roubineau, «Grèce ancienne: quotidiens et accidents»; «Identités et altérités alimentaires»; «Les goûts et les gestes»; «Diètes et écarts», dans Joël Cornette & Florent Quellier (dir.), Histoire de l’alimentation. De la préhistoire à nos jours, Paris, Belin, 2021, p. 169–263.

[1] Plutarch, Life of Alcibiades, 15, 7-8: ὀμνύουσι γὰρ ὅροις χρήσασθαι τῆς Ἀττικῆς πυροῖς, κριθαῖς, ἀμπέλοις, ἐλαίαις, οἰκείαν ποιεῖσθαι διδασκόμενοι τὴν ἥμερον καὶ καρποφόρον. “For they swear to use as boundaries of Attica wheats, barleys, vines, olives, being taught to consider as their own [land] that which is cultivated and fruit-bearing.” The same oath is found in two 4th century BCE documents: in Lycurgus, Against Leocrates, 77, and on the stele of Acharnae. These two texts additionally mention “figs” (συκαῖ) among the “boundaries of the homeland.”

[2] Herodotus, Histories, VIII, 55: ἔστι ἐν τῇ ἀκροπόλι ταύτῃ Ἐρεχθέος τοῦ γηγενέος λεγομένου εἶναι νηός, ἐν τῷ ἐλαίη τε καὶ θάλασσα ἔνι, τὰ λόγος παρὰ Ἀθηναίων Ποσειδέωνά τε καὶ Ἀθηναίην ἐρίσαντας περὶ τῆς χώρης μαρτυρία θέσθαι. “There is in this acropolis a temple of Erechtheus, who is said to be earth-born, in which there are an olive tree and a sea [salt water spring], which according to the tradition of the Athenians, Poseidon and Athena, disputing over the country, set down as testimonies.”

[3] Aristotle, Constitution of the Athenians, 60, 3: ἔστι γὰρ ἆθλα τοῖς μὲν τὴν μουσικὴν νικῶσιν ἀργύριον καὶ χρυσᾶ, τοῖς δὲ τὴν εὐανδρίαν ἀσπίδες, τοῖς δὲ τὸν γυμνικὸν ἀγῶνα καὶ τὴν ἱπποδρομίαν ἔλαιον. “For the prizes are: for the music contest, silver and gold objects; for the military bearing contest, a shield; finally for the gymnastic games and horse racing, oil.”

[4] Dioscorides, I, 34.

[5] Hesiod, Works and Days, v. 589-593: εἴη πετραίη τε σκιὴ καὶ βίβλινος οἶνος, μάζα τ᾽ ἀμολγαίη γάλα τ᾽ αἰγῶν σβεννυμενάων, καὶ βοὸς ὑλοφάγοιο κρέας μή πω τετοκυίης πρωτογόνων τ᾽ ἐρίφων. “Let there be the shade of a rock and wine from Byblos, a cake of curdled milk and milk of goats at the end of lactation, and meat of a heifer that browses in the woods and has not yet given birth, and of first-born kids.”

[6] Homer, Iliad, XI, 638-641, préparation of the kykeon (κυκεών): οἴνῳ Πραμνείῳ, ἐπὶ δ᾽ αἴγειον κνῆ τυρὸν κνήστι χαλκείῃ, ἐπὶ δ᾽ ἄλφιτα λευκὰ πάλυνε. “with Pramnian wine, and she grated goat cheese over it with a bronze grater, and sprinkled white barley meal on top”; II, 507: οἵ τε πολυστάφυλον Ἄρνην ἔχον. “those who possessed Arnè rich in grapes”; IX, 152 and 294: Πήδασον ἀμπελόεσσαν. “Pedasos rich in vines.”

[7] Homer, Odyssey, IX, 196-199: αἴγεον ἀσκὸν ἔχον μέλανος οἴνοιο ἡδέος, ὅν μοι ἔδωκε Μάρων, Εὐάνθεος υἱός, ἱρεὺς Ἀπόλλωνος, ὃ Ἴσμαρον ἀμφιβεβήκει. “I had a goatskin of sweet dark wine, which Maron, son of Euanthes, priest of Apollo who dwelt in Ismaros, had given me”; IX, 345-347: κισσύβιον μετὰ χερσὶν ἔχων μέλανος οἴνοιο: Κύκλωψ, τῆ, πίε οἶνον. “holding in my hands a cup of dark wine: Cyclops, here, drink wine.”

[8] Aristophanes, Assembly of Women, v. 305-308: ἀλλ᾽ ἡ̂κεν ἕκαστος ἐν ἀσκιδίῳ φέρων πιει̂ν ἅμα τ᾽ ἄρτον αὑτῳ̂ καὶ δύο κρομμύω καὶ τρει̂ς ἂν ἐλάας. “but each came carrying in a little wineskin something to drink, with bread, two onions and three olives.”

[9] Cited by Athenaeus of Naucratis, Deipnosophistae, VII, 278c-e.

[10] Herodotus, Histories, III, 106-107: Πρὸς δ’ αὖ μεσαμβρίης ἐσχάτη Ἀραβίη τῶν οἰκεομενέων χωρέων ἐστί, ἐν δὲ ταύτῃ λιβανωτός τε ἐστὶ μούνῃ χωρέων πασέων φυόμενος καὶ σμύρνη καὶ κασίη καὶ κινάμωμον καὶ λήδανον. “To the south, at the extremity of inhabited lands, lies Arabia; it is the only country where frankincense, myrrh, cassia, cinnamon and ladanum grow.” Herodotus then describes the legends about the dangers of their gathering.

[11] Aristophanes, The Birds, v. 531-535: ἀλλ᾽ ἐπικνω̂σιν τυρὸν ἔλαιον σίλφιον ὄξος. “but they sprinkle you with cheese, oil, silphion, vinegar”; and v. 1579-1580: φέρε σίλφιον: τυρὸν φερέτω τις. “bring the silphion: let someone bring the cheese.”.

[12] Archestratus, fragment cited by Athenaeus of Naucratis, Deipnosophistae, VII, 26 (295d-e): καὶ βατίδ᾽ ἑφθὴν ἔσθε μέσου χειμῶνος ἐν ὥρῃ, / κἀπ᾽ αὐτῇ τυρὸν καὶ σίλφιον ἅττα τε σάρκα / μὴ πίειραν ἔχῃ πόντου τέκνα, τῷδε τρόπῳ χρὴ / σκευάζειν. And eat the ray boiled in mid-winter, in season, and on it cheese and silphion, and all fish whose flesh is not fatty, must be prepared in this manner.”

[13] Theophrastus, History of Plants (Books VII à IX).