Translated from french (please notify us of errors)

It is the cocina that conceals the cocus. In other words, it is the “kitchen” that conceals the “cook”. Historians and commentators of ancient Rome have shown great interest in the preparation of dishes, but far less in those who prepared them.

“Those”, because they were probably almost exclusively men. Indeed, in Latin, the word coquus or cocus, which designates the cook, is masculine: the feminine form is – with one exception[1]– virtually non-existent: no coca. Women were of course in charge of the domestic hearth, but when the activity became professional, it was men who practised it. And yet there was nothing prestigious about it. Cooks were slaves, in the service of wealthy families.

For historians, the rise of the cook’s role occurred around the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE. At that time, the Roman elites were growing rich as never before. The eastern way of life, with its banquets and pleasures, exerted a considerable attraction upon them. The sober and austere habits that characterised Roman ethics gradually gave way to aristocratic lifestyles, which were in fact castigated by many authors, such as the severe Seneca.

Carptor, libarius and sublingio

In this context, it is certain that any Roman household worthy of the name (and with the means to do so) was expected to have at least one cook among its staff of slaves. That cook could moreover rise in rank and come to head a specialised brigade, including in particular a carptor (meat carver), a libarius (pastry cook) and even a sublingio (kitchen hand, literally a “licker” of dishes…).

In the 1st century BCE, the historian Livy bears witness to the changes under way:

“It was then that the cook, who among the Ancients had been regarded as the lowest of possessions, both in value and in use, began to be held in esteem, and what had previously been merely a function began to be considered an art. And yet all these novelties, which at that time attracted attention, were only the seeds of the luxury to come.”[2]

With this framework in place, let us turn to the story of Eros, who practised the profession of cocus in 1st-century Rome. We know a few fragments of his life because, being a prudent man, he had at least three tombstones prepared over the course of his lifetime. This does not point to any particular anxiety, but simply to the wish to end up using the one that reflected the highest social status he had attained.

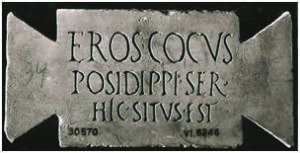

First stone, first stage: Eros cocus / Posidippi ser(vus) / hic situs est (Fig. 1). At this point, Eros is therefore a slave (servus) cook (cocus) in the service of a certain Posidippus.

Second stage, which we know from a stone that has since been lost but is recorded in volume VI of the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum published in 1876: Hic ossa sita sunt / Fausti Eronis / vicari supra / cocos. Eros is now head cook, supra cocos, a formula for which there are no other occurrences in epigraphy.

In fine, manumission

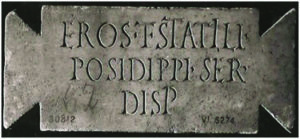

We then learn (Fig. 2) that Eros left the role of cook to take on that of dispensator, steward, administrator or treasurer. This remains a servile function, but doubtless the highest of them, since it involves managing the property of one’s master.

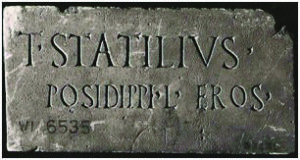

This is confirmed by a tombstone that was not intended for Eros, but for Faustus, described as his dearest friend (amicus amico) and deputy (vicarius) in his role as dispensator (Fig. 3).

Last stone, last stage in the life of Eros: T(itus) Statilius / Posidippi l(ibertus) Eros. The text is concise but decisive. It indicates that his master eventually freed Eros. Proof that, in ancient Rome, the culinary art could lead to anything – including freedom.

[1] The form coqua occurs once, in Plautus (Poen. 248).

[2] Livy, 39, 6, 9: Tum coquus, uilissimum antiquis mancipium et aestimatione et usu, in pretio esse, et quod ministerium fuerat, ars haberi coepta. Vix tamen illa quae tum conspiciebantur semina erant futurae luxuriae.

Sources

- Mourir pour un ami. Le cas de Faustus, vicarius d’ Éros d’ après CIL VI 6275, Marianne Béraud, Dans Dialogues d’histoire ancienne 2016/1 (42/1), pages 177 à 200.

- Être cuisinier dans l’Occident romain antique, Marie-Adeline Le Guennec, Archeologia Classica, Vol. 70 (2019), pp. 295-328 (34 pages).

Other articles in English from the Nunc est bibendum blog