Translated from french (please notify us of errors)

In this 13-hectare complex, equipped with swimming pools, gymnasiums, libraries and food stalls, three thousand people thronged daily. No, we are not in a contemporary spa resort, but in the Baths of Diocletian, at the heart of imperial Rome. In the 4th century, the capital boasted no fewer than 952 public bath establishments[1].

The design of Roman baths demonstrates ingenious refinement: the caldarium, overheated by hot air ducts circulating in the walls and beneath the floors (so scorching that special sandals had to be worn[2]), lthe temperate tepidarium, and finally the frigidarium with its icy pools. A thermal journey designed for the senses.

Balnea Vina Venus

Demonstrating the importance of baths (but not only that), a certain Merope had engraved in the 1st century CE on the tomb of her companion Tiberius Claudius Secundus a formula popular at the time: balnea vina Venus corrumpunt corpora nostra, sed vitam faciunt – “baths, wine and sex ruin our bodies, but make life worth living”[3].

The commissioner of the inscription, an imperial freedwoman, mourns her “dear life companion” who died at 52. In her grief, she breaks funerary conventions: instead of extolling the civic virtues of the deceased, she chooses to celebrate the pleasures that illuminated their existence. Even more audaciously, the epitaph states that he “has everything with him” in the tomb (hic secum habet omnia) – as if these earthly pleasures accompanied him into the afterlife.

This choice is not isolated. Throughout the Empire, variants of this hedonistic philosophy are carved into stone and metal.

At Ostia, Domitius Primus boasts in the 3rd century: “I have lived on oysters from Lucrine, I have often drunk Falernian wine. Baths, wines and love have grown old with me.”[4]

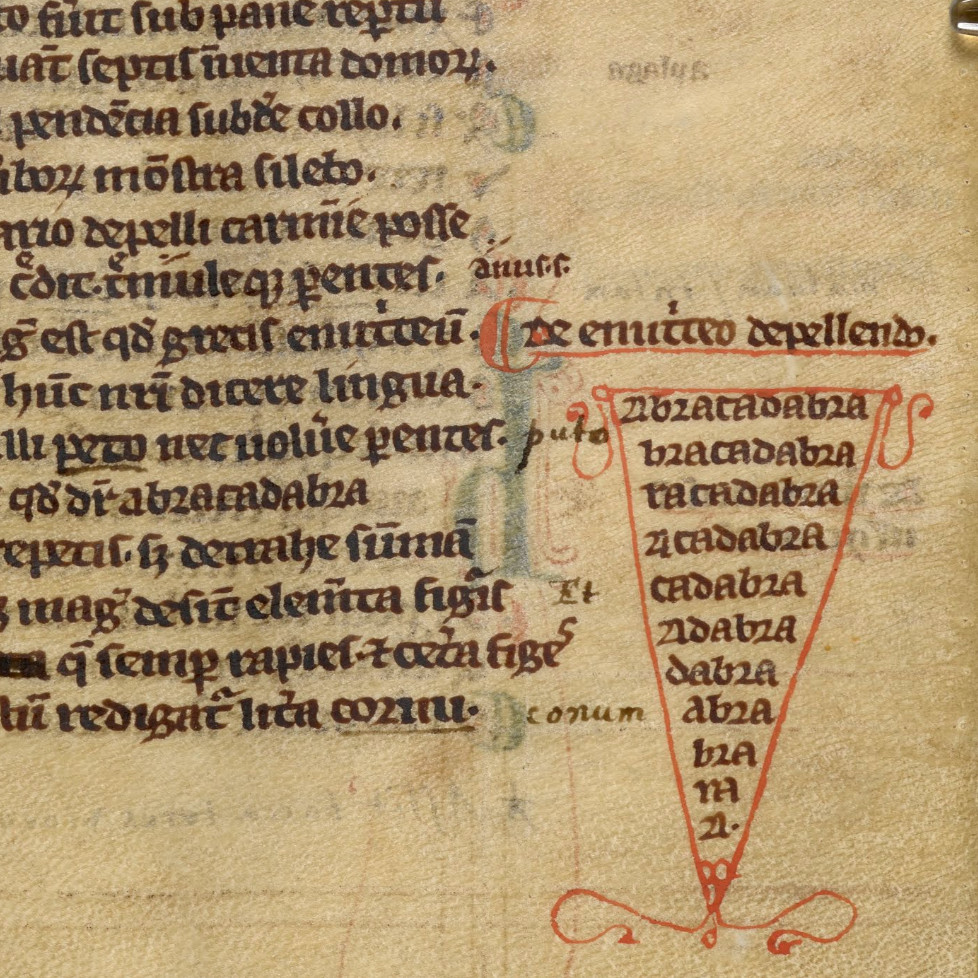

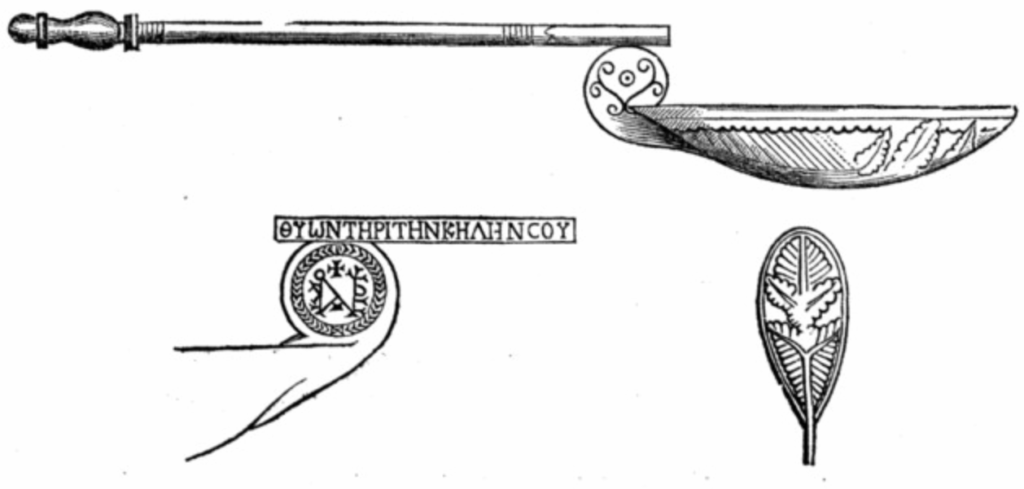

Among the known objects bearing the same maxim is a large silver spoon found in the mid-19th century at Nea Lampsakos, present-day Gallipoli (Gelibolu) on the northern shore of the Dardanelles in Turkey. The object was lost in a fire in 1922, but we have a precise record[5]. In the bowl of the spoon one could read, spread over two lines:

BALNEA VINA VENUS FACIUNT PRO/PERANTIA FATA

Literally meaning “Baths, wines and Venus make hastening fates”. In other words: life’s pleasures subjectively accelerate the passage of time, which can be understood as both an encouragement and a warning.

The same spoon bore a second inscription, this time in Greek, on the square section of the handle:

ΘΥΩΝ ΤΗΡΙ ΤΗΝ ΚΗΛΗΝ ΣΟΥ

Which means “when you sacrifice, watch your hernia”. A most mysterious sentence… for those unfamiliar with a certain epigram by Martial. Indeed, the poet recounts a misadventure that can be directly related to the inscription.

An Etruscan haruspex asks a peasant to castrate a goat before sacrificing it to Bacchus. While the haruspex bends down to slaughter the animal, a “hernia” (an imagistic evocation of another appendage) suddenly appears, which the naïve peasant takes for part of the sacrifice and immediately cuts off. The soothsayer thus finds himself involuntarily castrated and transformed into a eunuch priest. From Tuscus (Etruscan), he becomes Gallus (the name given to the eunuch priests of the cult of Cybele who self-mutilated). [6]

The lost spoon thus combines Epicurean wisdom with ribald erudition. This philosophy of pleasure finds its privileged terrain of expression in the baths.

Seneca, who lives above a thermal complex around 50 CE, immerses us in this atmosphere by describing it to his friend Lucilius[7]:

“Now imagine all kinds of voices that can make the ears hateful: when the strongest exercise and throw their hands weighted with lead, when they strain or imitate one who strains, I hear groans; whenever they release their held breath, whistling and very harsh breathing; when I encounter some lazy fellow content with this popular massage, I hear the slapping of the hand striking the shoulders, which changes sound depending on whether it arrives flat or hollow. But if the ball player appears and begins to count the balls, it’s all over!

Add now the quarreller and the thief caught in the act, and he whose voice pleases him in the baths; add also those who jump into the pool with the great noise of the water they push. Besides those whose voices, if nothing else, are at least straight, think of the hair-plucker raising his thin and strident voice to be better noticed, never falling silent except when he plucks hairs and makes another cry in his place; then the varied cries of the drink seller, the sausage maker, the pastry cook and all the tavern merchants selling their wares each with his particular and distinctive modulation.”

Democratisation of Luxury and Social Hierarchies

Contrary to received ideas, Roman baths were not reserved for an elite. Entry fees remained derisory, or even free during festivals and political campaigns, allowing all social classes to access these amenities.

But social hierarchy reconstituted itself within the thermal space itself. Certain aristocrats arrived escorted by fifty servants[8], and spaces were reserved for them to display their most sumptuous attire.

The separation of the sexes was strictly observed, women and men bathing at different times. The physician Soranus of Ephesus even recommended that women frequent the baths in preparation for childbirth[9].

The evolution of the ancient triad of baths-wine-sex reveals the profound transformations of Western mentalities. Baths, symbol of Roman refinement, gradually disappear from medieval European culture, victims of Christian mistrust of bodily pleasures and the collapse of urban infrastructure. The pleasures of Venus, meanwhile, find themselves strictly regulated by Christian morality which opposes chastity and lust, transforming the ancient celebration of love into a source of guilt. Only wine better resists this transformation, finding its place in Christian liturgy whilst retaining its convivial connotations.

If the triad reappears in an 18th-century collection, it is to undergo categorical condemnation: balnea, vina, Venus virtutis vera venena “Baths, wine, Venus are the true poisons of virtue”[10].

[1] The Chronography of 354 AD. Part 14: Notice of the 14 regions of the City.

[2] PBS Nova, “Roman Baths: The Caldarium”, cited in The Conversation, Baths, wine, and sex make life worth living

[3] CIL VI, 15258, Rome, 1st century CE: V(ixit) an(nos) LII d(is) M(anibus) Ti(beri) Claudi Secundi hic secum habet omnia balnea vina Venus corrumpunt corpora nostra se<d=T> vitam faciunt b(alnea) v(ina) V(enus) karo contubernal(i) fec(it) Merope Caes(aris) et sibi et suis p(osterisque) e(orum).

[4] CIL XIV, 914 : D(is) M(anibus) C(aius) Domiti Primi hoc ego su(m) in tumulo Primus notissi mus ille vixi Lucrinis pota<v=B>i saepe Fa lernum baln<e=I>a vina Venus mecum senuere per annos hec(!) ego si potui sit mihi terra lebis(!) et tamen ad Ma nes foenix(!) me serbat(!) in ara qui me cum properat se reparare sibi l(ocus) d(atus) funeri C(ai) Domiti Primi a tribus Messis Hermerote Pia et Pio.

[5] CIL III 12274c. Salomon Reinach, Une cuiller d’argent du musée de Smyrne, Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique, 1882, 6, pp. 353-355.

[6] Martial, Epigrams, III, 24: Vite nocens rosa stabat moriturus ad aras / hircus, Bacche, tuis uictima grata focis; / quem Tuscus mactare deo cum uellet aruspex, / dixerat agresti forte rudique uiro / ut cito testiculos et acuta falce secaret, / taeter ut inmundae carnis abiret odor. / Ipse super uirides aras luctantia pronus / dum resecat cultro colla premitque manu, / ingens iratis apparuit hirnea sacris. / Occupat hanc ferro rusticus atque secat, / hoc ratus antiquos sacrorum poscere ritus / talibus et fibris numina prisca coli.

Coupable d’avoir grignoté une vigne, se tenait près de tes autels un bouc destiné à mourir, ô Bacchus, victime agréable à tes foyers. Comme l’haruspice étrusque voulait l’immoler au dieu, il avait dit par hasard à un paysan rustique et grossier de couper rapidement les testicules avec une faucille aiguisée, afin que s’en allât l’odeur fétide de cette chair immonde. Lui-même, penché au-dessus des verts autels, tandis qu’il tranchait au couteau le cou qui se débattait et le maintenait de la main, une énorme hernie apparut, au grand scandale des rites sacrés. Le paysan s’en empare avec son fer et la coupe, pensant que les anciens rituels des sacrifices exigeaient cela et que les divinités antiques étaient honorées par de telles entrailles. Ainsi, toi qui étais tout à l’heure haruspice étrusque, te voilà maintenant haruspice galle : en égorgeant un bouc, tu es devenu toi-même un chevreau.[7] Seneca, Letters to Lucilius, Letter 56, around 50 CE: [1] (…) Propone nunc tibi omnia genera vocum quae in odium possunt aures adducere: cum fortiores exercentur et manus plumbo graves iactant, cum aut laborant aut laborantem imitantur, gemitus audio, quotiens retentum spiritum remiserunt, sibilos et acerbissimas respirationes; cum in aliquem inertem et hac plebeia unctione contentum incidi, audio crepitum illisae manus umeris, quae prout plana pervenit aut concava, ita sonum mutat. Si vero pilicrepus supervenit et numerare coepit pilas, actum est. [2] Adice nunc scordalum et furem deprensum et illum cui vox sua in balineo placet, adice nunc eos qui in piscinam cum ingenti impulsae aquae sono saliunt. Praeter istos quorum, si nihil aliud, rectae voces sunt, alipilum cogita tenuem et stridulam vocem quo sit notabilior subinde exprimentem nec umquam tacentem nisi dum vellit alas et alium pro se clamare cogit; iam biberari varias exclamationes et botularium et crustularium et omnes popinarum institores mercem sua quadam et insignita modulatione vendentis.

[8] Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, 28, account from the 4th century CE.

[9] Soranus of Ephesus, Treatise on Gynaecology, 2nd century CE.

[10] Florilegium Latinum, sive Hortus Proverbiorum, par D. Joannem de Lama, Madrid, 1769, p. 330

Other articles in English from the Nunc est bibendum blog