Translated from french (please notify us of errors)

In the 3rd century AD, had you been suffering from a fever in Rome, a physician might have prescribed a surprising treatment: wearing around your neck an amulet inscribed with the word ABRACADABRA, repeated eleven times with one letter removed at each line until only a solitary A remained.

This medical prescription comes to us from Quintus Serenus Sammonicus, a scholar of the Severan era whose Liber Medicinalis bears witness to a medicine in which magic and therapeutics were one and the same.

An imperial remedy against malaria

The passage of the Liber Medicinalis devoted to tertian fever (malaria) sets out the method with precision:

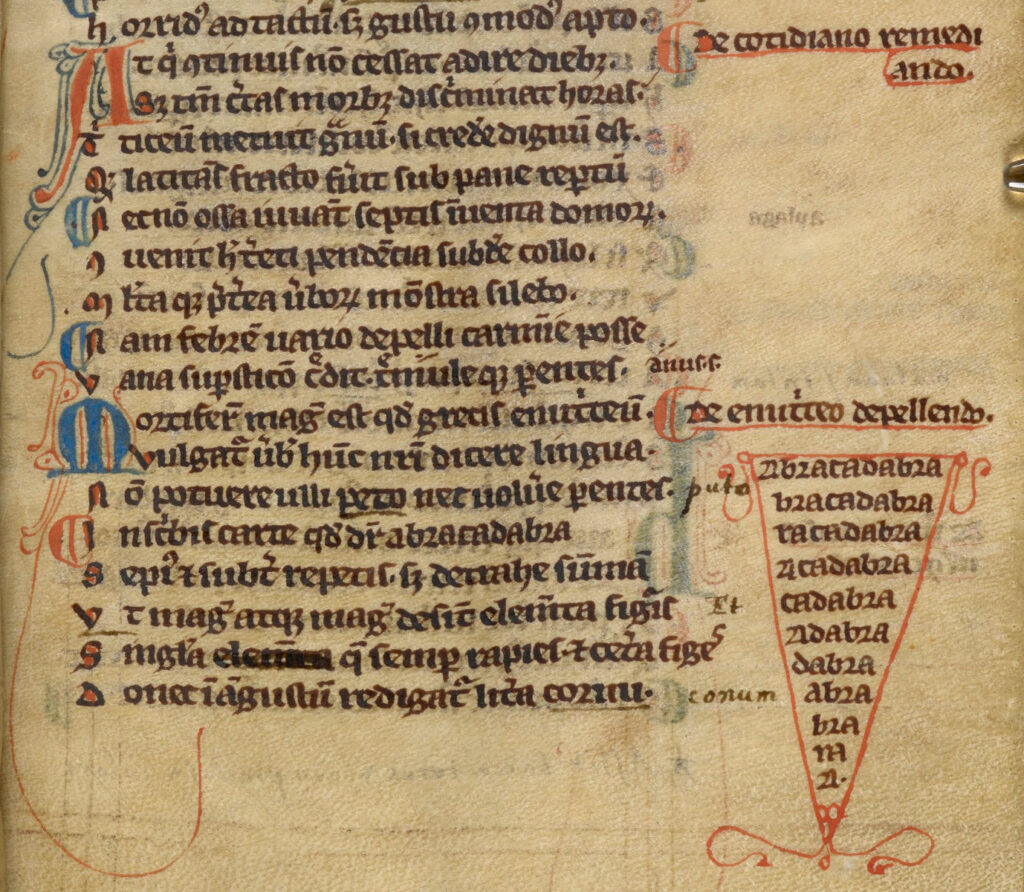

“You shall inscribe on a sheet of paper what is called abracadabra, and you shall repeat it several times below, but you shall remove the last letter, and more and more shall the letters be missing from the lines one by one, which you shall always take away, until the letter is reduced to a narrow cone: you shall remember to encircle your neck with this, bound with linen”[1].

This triangular formula, pointing downwards, represented according to the Greeks a heart or a bunch of grapes. The procedure aimed to transcribe an oral tradition: vanquishing an evil spirit by repeating and reducing its name until complete silence was achieved. For according to the beliefs of the time, spirits sowed disease, and these diminishing incantations were intended to cure fever and other ailments.

The career of a Severan scholar

Quintus Serenus Sammonicus was no mere compiler of magical recipes. Edward Champlin, in a study published in 1981 in Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, reconstructed the portrait of a figure of considerable importance in his day. Described as “the most learned man of his century”[2] by Macrobius, Sammonicus was close to the emperor Septimius Severus and probably served as tutor to the princes Geta and Caracalla.

This position ultimately cost him his life: a partisan of Geta, he was murdered along with other loyalists of the prince during the purges that followed his assassination by Caracalla in the closing days of the year 211. The Historia Augusta reports soberly: “some were also killed whilst dining, among them Sammonicus Serenus, whose many books survive for the purposes of learning”[3].

His reputation nevertheless survived the dark years of the 3rd century. Arnobius and Servius drew on his erudition, Macrobius plundered him for whole sections of the Saturnalia, and Sidonius Apollinaris was familiar with his works. His principal work, the Res Reconditae, presented in at least five books, compiled knowledge on subjects as varied as Roman sumptuary laws, sturgeon scales, the secret formulae for invoking the tutelary deities of besieged cities, and the midnight sun in Thule.

Papyri bearing witness to the remedy’s popularity

The recipe reported by Sammonicus enjoyed a remarkable diffusion in Late Antiquity, as two documents held at the University of Michigan attest.

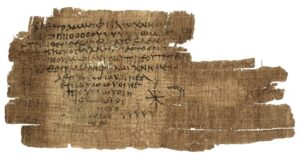

A Greek papyrus from the 3rd century, originating from Egypt, perfectly illustrates the practical application of this therapeutic magic. After a prayer to the gods — “Lord Gods, heal Helene, whom X bore, of every disease and every assault of shivers and fever, ephemeral, quotidian, tertian, quartan”[4] — the text presents a sophisticated variation of the formula.

The seven Greek vowels are first arranged in increasing numbers until they reach 28 occurrences, symbolising the seven planets visible to the naked eye and the 28 phases of the moon. Three stars and a crescent moon surround the final lines, reinforcing this invocation to the supreme deity who governs the celestial movements. Then comes an inverted triangle formed by the vowels arranged as a palindrome, progressively losing the first and last letter of each line. This ingenious arrangement suggests that what disappears is not the protective deity but its malevolent opposite.

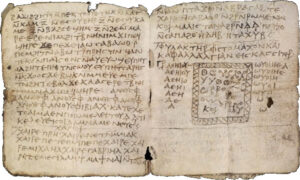

A Coptic codex from the 6th century, also held at Michigan, testifies to the persistence of this practice. This small manuscript of seven leaves compiles popular recipes and healing formulae for gout, eye diseases, toothache, fevers, pregnancy, and abdominal and mental disorders. On page 8, one finds a variation of Sammonicus’s recipe: two series of vowels arranged in inverted triangles, to be written on a tin plate, interrupted by the drawing of a square containing rings.

The disputed origins of a magical formula

The etymology of abracadabra has long been a matter of debate. Some scholars propose the Hebrew ebrah k’dabri (“I create with the word”) or the Aramaic avra gavra (“I shall create man”), the words spoken by the biblical God on the sixth day of creation. Other scholars favour the Hebrew expression ha brachah dabrah (“Name of the Blessed”), a common magical formula. This explanation seems plausible, for divine names constituted important sources of supernatural healing and protective power in ancient magic. Among the early Christians, names derived from Hebrew were held in high esteem, as it was the language of God and of creation.

The formula retained its therapeutic function for several centuries. Thus, a 16th-century Hebrew manuscript from Italy mentions a variant of the spell inscribed on an amulet protecting against fever. The British writer Daniel Defoe reports in his A Journal of the Plague Year that the formula was still in use in 17th-century London to ward off infection, “as if the plague was not the hand of God, but a kind of possession of an evil spirit”.

Yet the word gradually lost its value as a remedy, becoming by the 19th century a mere conjuror’s formula.

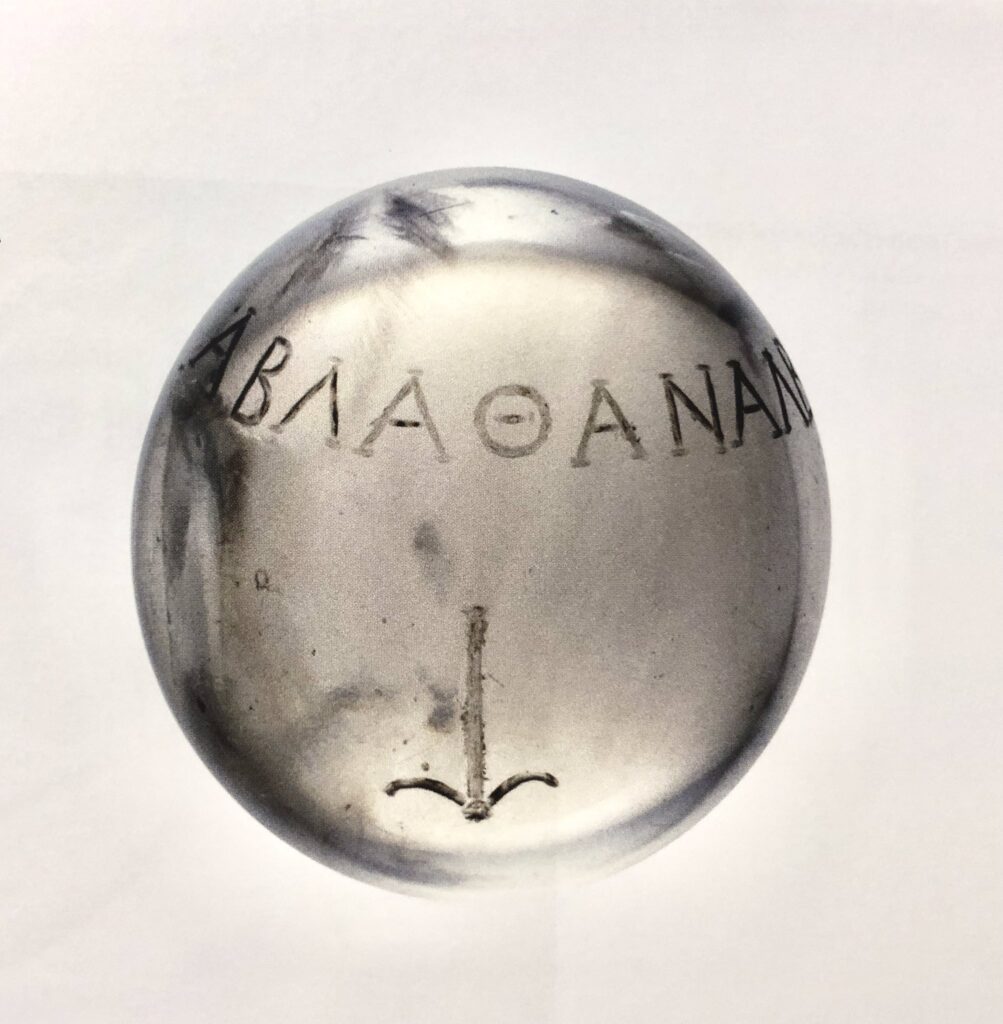

A Roman crystal ball in Denmark

The magical use of formulae closely resembling that of Sammonicus spread well beyond the borders of the Roman Empire. A rock crystal sphere nearly three centimetres in diameter, discovered in a tomb dating to around AD 300 at Årslev in Denmark, bears the inscription ΑΒΛΑΘΑΝΑΛΒΑ engraved in Greek characters[5]. This formula constitutes an abbreviated form of the full palindrome ΑΒΛΑΝΑΘΑΝΑΛΒΑ. Known from several Mediterranean amulets, it is linked to the cult of the god Abrasax.

Abraxas (or Abrasax) denotes in Christian Gnosticism the “Great Archon”, lord of the 365 heavens. His name, calculated according to Greek numerology (isopsephy), yields precisely 365, the number of days in the year: Α=1, Β=2, Ρ=100, Α=1, Σ=200, Α=1, Ξ=60. This Gnostic deity was associated with cosmic power and protection against disease. The palindrome ΑΒΛΑΝΑΘΑΝΑΛΒΑ, generally considered to derive from Hebrew or Aramaic אב לן את, would mean “Thou art our father”.

Beneath the inscription on the Årslev sphere is a small anchor. This is perhaps an early Christian symbol representing the hope of the soul which, after a long and perilous voyage, at last casts anchor in a safe harbour. What is certain is that classical authors attributed curative properties to rock crystal: it could quench thirst, cool and cure fever. And, when one looks through the sphere, the world appears upside down — a property that reinforced the perception of magical power!

[1] Quintus Serenus Sammonicus, Liber Medicinalis, vv. 934–940: inscribes chartae quod dicitur abracadabra saepius et subter repetes, sed detrahe summam et magis atque magis desint elementa figuris singula, quae semper rapies, et cetera †figes, donec in angustum redigatur littera conum: his lino nexis collum redimire memento.

[2] Macrobius, Saturnalia 3.16.6: vir saeculo suo doctus.

[3] Historia Augusta, Life of Caracalla 4.4: occisique nonnulli etiam cenantes, inter quos etiam Sammonicus Serenus, cuius libri plurimi ad doctrinam extant.

[4] Papyrus P. Mich. inv. 6666 (3rd century), lines 3–5: Κύριοι θεοί, ὑγίανατε Ἑλένην, ἣν ἔτεκεν ἡ δεῖνα, ἀπὸ παντὸς πυρετοῦ καὶ ῥίγους ἐπηρείας, ἐφημέρου, ἀμφημέρου, τριταίου, τεταρταίου.

[5] Nationalmuseet, Copenhagen, “A mysterious crystal ball”.

Modern studies

- Edward Champlin, “Serenus Sammonicus”, Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, vol. 85, 1981, pp. 189–212.

- Pablo Alvarez, “Abracadabra!”, Beyond the Reading Room (University of Michigan Library), 12 December 2016.

- Genevra Kornbluth, “Pilulae and Bound Pendants: Roman and Merovingian Amulets”, in Magical Gems in their Contexts, 2019.

Other articles in English from the Nunc est bibendum blog