Translated from french (please notify us of errors)

In Pompeii, three elegiac distichs painted on the walls of a dining room dictate the rules of propriety to the guests. These unique inscriptions blend learned poetry and social etiquette in a meticulous staging of the convivial space.

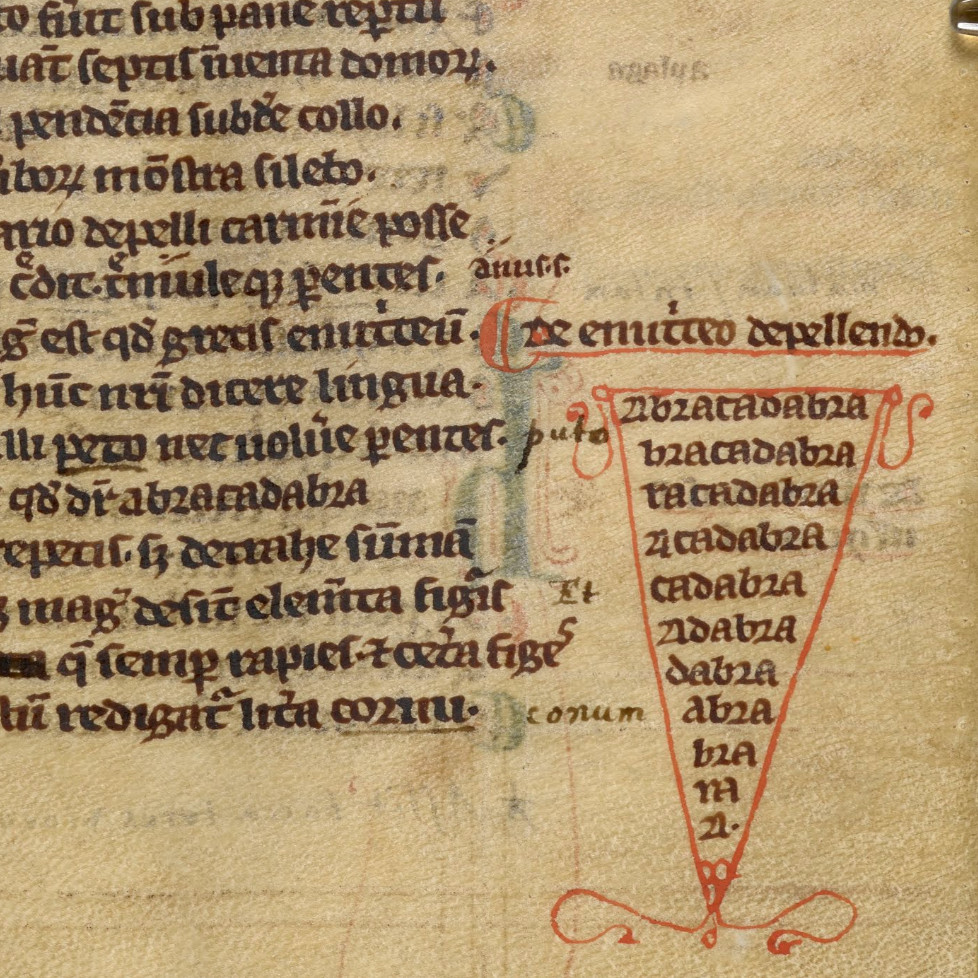

In Regio III of Pompeii, the House of the Moralist (Casa del Moralista) owes its modern name to an unusual decoration: its summer triclinium, a 25 m² room open to the garden, features three elegiac distichs painted in white letters on a black background. A unique case in the Campanian city, these metrical inscriptions transform the walls into a support for moral discourse addressed to the guests. The house, excavated in the early 20th century by Vittorio Spinazzola, most likely belonged to Caius Arrius Crescens, whose name appears on a bronze seal found in the wine cellar.

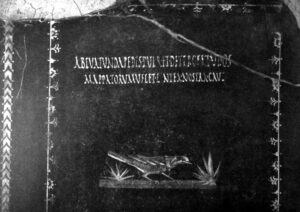

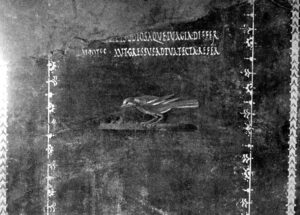

The 1944 bombings destroyed the western wall and its inscription. The photographs taken in 1927 by Matteo Della Corte now constitute the only direct testimonies of the original state. An inspection conducted in July 2019 by the authors of the recent study that serves as the basis for this article (see reference below) confirmed the advanced deterioration of the remaining paintings. The texts are now readable only thanks to the photographic archives, which makes their scientific publication all the more valuable.

The three masonry couches, arranged in a U-shape around a central marble table, traditionally accommodated nine guests. Each inscription occupies a precise position: above the lectus summus (upper couch) on the north wall, the lectus medius (central couch) on the west wall, and the lectus imus (lower couch) on the south wall. This arrangement is not fortuitous. The order of the texts corresponds to the different moments of the banquet, from the arrival of the guests to the risks of late-evening excesses.

A three-stage protocol

The first distich, visible from the lectus summus, addresses the servant:

Abluat unda pedes puer et detergeat udos. / Mappa torum velet, lintea nostra cave

“Let water wash the feet and let the slave dry them, wet. / Let the cloth cover the couch. Take care of our napkins”

The washing of feet, a practice attested by Petronius in the Satyricon, marks the beginning of the meal. The Latin author describes the welcome at Trimalchio’s: “At last, then, we reclined at table, Alexandrian boys pouring iced water over our hands”[1]. The mappae, these napkins used to wipe hands and mouth, are also part of the Petronian décor.

The second couplet invites restraint:

Lascivos voltus et blandos aufer ocellos / coniuge ab alterius, sit tibi in ore pudor

“Keep away lascivious looks and cajoling eyes / from another’s wife, but let modesty be on your face”

The vocabulary borrows directly from elegiac poetry. The expression in ore pudor refers back to Ovid, who writes in the Tristia: purpureus molli fiat in ore pudor (“Let blushing modesty appear on the soft face”)[2]. The ocelli (little eyes) constitute a typically elegiac term, found in Catullus and Tibullus.

The third distich, partially lacunose at the beginning of the first verse[3], warns against quarrels:

[insana]s litis odiosaque iurgia differ / si potes aut gressus ad tua tecta refer!

“Postpone [insane] disputes and hateful altercations / if you can, or bring your steps back to your dwelling!”

Here again, the Ovidian source prevails. In the Fasti, the poet wishes for the new year: lite vacent aures, insanaque protinus absint / iurgia (“Let ears be free from litigation, let insane quarrels be immediately absent”)[4]. The Satyricon confirms the frequency of rixae at banquets, particularly late in the evening under the influence of wine.

The art of poetic reappropriation

The anonymous author of these inscriptions masters the technique of oppositio in imitando. He does not quote Ovid verbatim, but recombines expressions from different contexts to create new verbal associations. Thus, the injunction to avoid lascivious looks at another’s wife recalls several passages from the Amores and the Ars amatoria, but the specific formulation is found nowhere as such in the poet. Similarly, the formula abluat unda pedes evokes Catullus: pallidulum manans alluit unda pedem (“The flowing water bathes the pale foot”)[5], but the entire verse constitutes an original creation.

This practice confirms the high cultural level of the patron. The three couplets scrupulously respect elegiac metrics, with the hexameter-pentameter alternation characteristic of the distich. The letters, about 3 cm high, generally follow a regular baseline. Words are separated by dots, and some vowels bear apex, these accents marking long vowels. The execution shows particular care, even if the right alignment remains irregular.

The dating of these inscriptions is established between 50 and 79 CE based on the electoral tituli picti present on the facade of the house. The wall decoration in the Fourth Style, characteristic of the mid-first century, confirms this chronology. The garden trees, still young at the time of the eruption of Vesuvius in 79, indicate that the arrangement dates from only a few decades before the catastrophe.

Serious warning or learned game?

The Casa del Moralista raises the question of how these maxims were received by the guests. Are these serious warnings or a learned game intended to amuse cultured guests?

For the authors of the recent study cited, the second hypothesis seems plausible. The choice of the elegiac genre, associated with amorous and light poetry, suggests a playful dimension. An owner with the means to adorn his triclinium with carefully crafted metrical verses was probably seeking as much to demonstrate his erudition as to effectively regulate the behavior of his hosts.

The influence of Ovid in these domestic texts testifies to the diffusion of Latin poetry beyond learned circles. Other Pompeian graffiti quote or paraphrase Ovid, Propertius, or Virgil, sometimes in more trivial contexts. The basilica of Pompeii thus preserves three graffiti reproducing verses by Ovid and Propertius. This shared poetic culture constituted a social marker and an element of distinction for municipal elites.

The parallels with Petronius’s Satyricon illuminate the actual functioning of Roman banquets. At Trimalchio’s, the mappae serve to carry away leftovers, servants wash guests’ feet with ice water, and disputes regularly break out, fueled by “the insolence of drunkards” (insolentia ebriorum)[6]. The contrast between the ideal expressed by the Pompeian distichs and the reality described by Petronius perhaps underscores the necessity of these reminders.

Main sources

- Gianmarco Bianchini, Rosy Bianco, Gian Luca Gregori, The triclinium of the ‘Casa del Moralista’ and Its Inscriptions: CIL IV, 7698 = CLE 2054″, Sylloge Epigraphica Barcinonensis 18, 2020, pp. 85-105.

- M. Della Corte, «Scavi sulla Via dell’Abbondanza (Epigrafi inedite)», Notizie degli Scavi di Antichità (NSc), 1927, n. 1-2-3, p. 93–97, tavv. X–XI.

[1] Petronius, Satyricon 31, 3: Tandem ergo discubuimus, pueris Alexandrinis aquam in manus nivatam infundentibus.

[2] Ovid, Tristia 4, 3, 70.

[3] The loss of the first part of the third hexameter has prompted numerous restoration proposals. The reading [insana]s litis, proposed by Pierleoni and confirmed by analysis of the 1925 photographs, is based on the Ovidian parallel from the Fasti. The traces still visible on the plaster in 1925 clearly show the letters LITIS, not LITES as some early editors had read. The available space, between 7 and 9 letters according to the ordinatio of the other verses, corresponds exactly to [insana]s.

[4] Ovid, Fasti 1, 73-74.

[6] Petronius, Satyricon 70, 6.

Other articles in English from the Nunc est bibendum blog