Translated from french (please notify us of errors)

In ancient Rome, the name “Apicius” resonated as that of the consummate gourmet. Yet behind this appellation lie in fact three distinct individuals, all united by an excessive love of the pleasures of the table. The confusion between them, already present in Antiquity, shows how a simple cognomen came to embody Roman culinary refinement in its most extravagant form.

The first Apicius is known to us through Athenaeus of Naucratis, who cites the historian Posidonius. This man lived at the beginning of the first century BCE and “surpassed all other men in matters of intemperance”[1]. His life remains obscure, and we do not know precisely how that asōtia (intemperance) ascribed to him in the Greek text manifested itself. Curiously, he is said to have caused the banishment of Publius Rutilius Rufus in 92 BCE, though the reasons for this are not explained. Strikingly, Athenaeus adds that there existed another Apicius, much more famous, who left behind the same memory of excess — showing that the reputation attached to the name “Apicius” was built very early around an idea of overindulgence at table.

Marcus Gavius Apicius, the paradigm of luxury

The second Apicius, Marcus Gavius, remains the best known. Born around 25 BCE, this millionaire lived under Augustus and Tiberius before committing suicide around 37. Tacitus mentions him briefly in the Annals, noting rumours that the young Sejanus had prostituted himself “to the rich and prodigal Apicius”[2]. But it is above all Seneca who paints the most striking portrait of the man, in his Consolation to Helvia:

“This Apicius, who threw one hundred million sesterces into his kitchen, who at each of his banquets swallowed so many imperial largesses and the enormous revenues of the Capitol, at last, crushed by debt, was forced for the first time to look at his accounts. He calculated that he had ten million sesterces left; and, as if he must die of hunger living with a mere ten million, he ended his life by poison.”[3]

The tragic death of a man who preferred to die rather than live what he deemed a miserable life with “only” ten million sesterces leaves a lasting impression. This sum, in Tiberius’s time, would have been sufficient to pay the annual salary of over 11,000 legionaries –the equivalent of two complete legions. For Seneca, Apicius embodied the corruption of Roman morals: he had “professed the science of the tavern” (scientiam popinae) and “infected his age with his teaching”[4], as if he had elevated the art of culinary debauchery to the level of a doctrine. In other words, Apicius was not merely a wealthy glutton: he was a public corrupter.

Ancient sources abound with anecdotes of his culinary extravagance. Pliny the Elder reports several of his innovations: Apicius fattened sows on dried figs, then killed them abruptly after giving them honeyed wine, in order to improve their livers. He also devised a brine based on red mullet liver and declared that “the tongue of the flamingo was of the most exquisite flavour”[5]. Pliny even attests to an “Apician cooking method” (apiciana coctura)[6], consisting in macerating vegetables, such as cabbage, in oil and salt before cooking — in other words, giving them a luxurious treatment. The influence of Apicius extended as far as the imperial family: Drusus Caesar, son of Tiberius, is said to have refused young cabbage shoots (cyma) under his influence, to the point that he was reprimanded by Tiberius himself[7].

Athenaeus tells an anecdote that has become emblematic: living at Minturnae, in Campania, where he enjoyed exceptionally large shrimps, Apicius heard praise for those from the African coast. He immediately chartered a ship, fell ill at sea, reached the African shores … and, after inspecting the crustaceans brought on board by local fishermen, ordered an immediate return, judging the creatures inferior to those of Minturnae[8]. He never even set foot on land. Here, culinary luxury becomes an obsessive quest for the absolute.

The Art of Gastronomic One-upmanship

Seneca recounts yet another revealing episode from the milieu in which Apicius moved. A red mullet of exceptional size was offered to Tiberius, who chose to have it sold at the market. The emperor announced: “I am much mistaken if this mullet is not purchased by Apicius or by Publius Octavius.” The two men indeed bid against each other, and Octavius won for five thousand sesterces, thus acquiring “immense glory for having bought, for five thousand sesterces, a fish that Caesar had sold and that even Apicius had failed to obtain”[9].

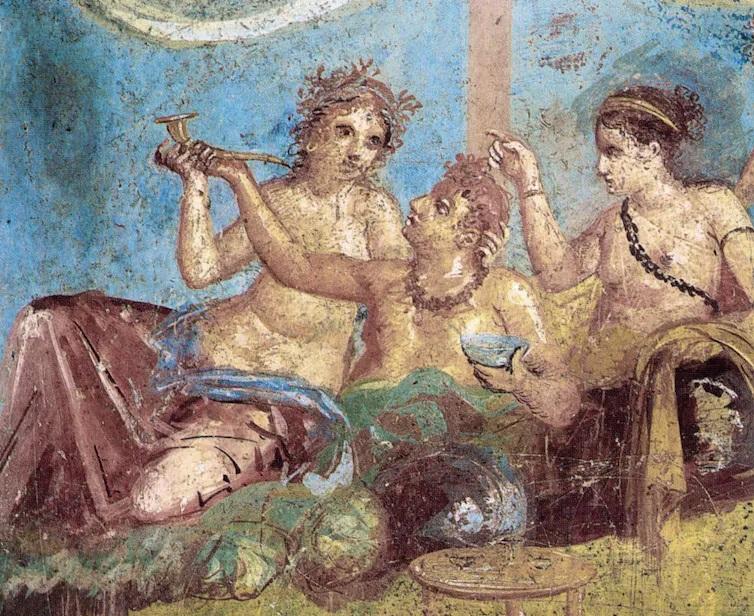

This scene illustrates the competition that reigned among Rome’s very wealthy regarding culinary luxury. Buying a fish became a public act of prestige. Apicius stood at the intersection of consumption, connoisseurship, elite sociability, and — crucially — the ability to turn dining into political spectacle. Some modern analyses even suggest that he may occasionally have benefited from public funds to organise banquets designed to impress foreign dignitaries, making his table an instrument of diplomacy as well as a theatre of excess.

From a Proper Name to a Gastronomic Myth

The third Apicius lived under the emperor Trajan, at the beginning of the second century CE. Athenaeus reports yet another anecdote, this one almost technological: “When Emperor Trajan was in Parthia, several days’ journey from the sea, Apicius sent him fresh oysters whose freshness he had preserved by a method of his own invention”[10]. Here we are no longer dealing merely with reckless expenditure, but with mastery of preservation techniques allowing delicate products to reach the very frontiers of the Empire. It is already a form of culinary engineering of luxury.

The progressive confusion between these three figures is easily explained. By the end of the second century, the name “Apicius” no longer referred merely to an individual, but to a type — the consummate gourmet. Tertullian notes that, just as philosophers derive their names from their masters (Platonists, Epicureans, etc.), “cooks took their name from Apicius”[11]. In other words, by the dawn of Late Antiquity, “an Apicius” could already mean “a chef of luxury.”

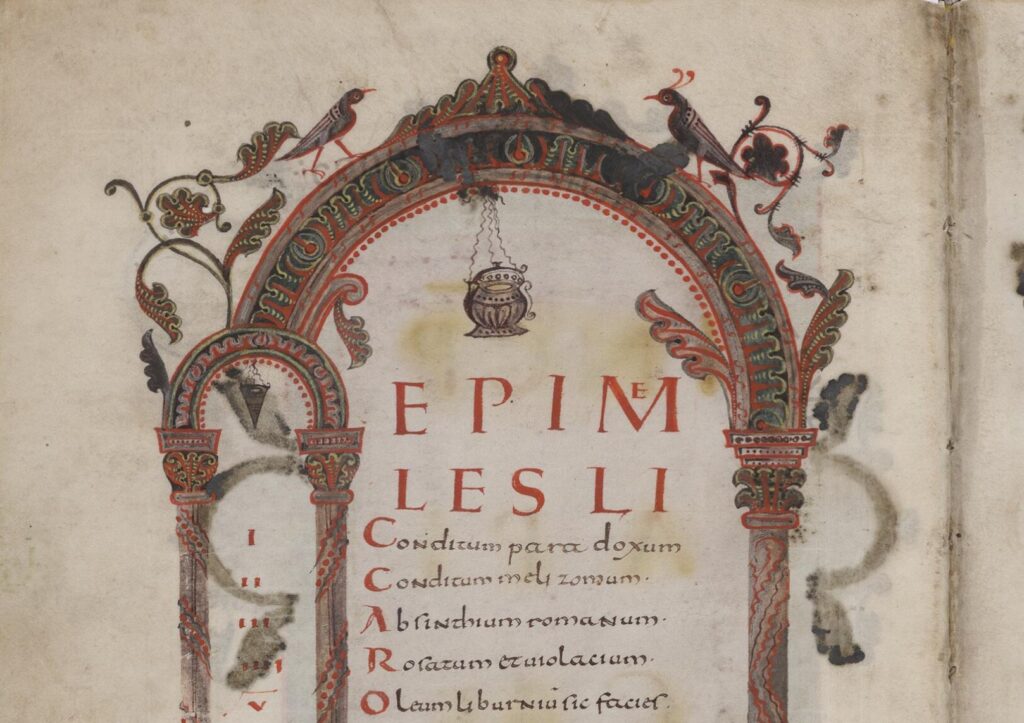

It is in this context that the De re coquinaria, traditionally attributed to Apicius, appears. The text we possess is a late compilation, fixed in the fourth century, containing nearly five hundred recipes organised into thematic books. It cannot be a work written directly by Marcus Gavius Apicius under Tiberius: it contains later strata and references to later periods. Yet this collection — clearly intended for professional cooks rather than amateurs — perpetuates his name. It documents a cuisine that is resolutely international, rich in costly ingredients, exotic spices, and thick sauces based on garum. Above all, it remains our only extensive continuous culinary source preserved from the Graeco-Roman world.

The story of the three Apicii thus illustrates how a proper name can become a cultural symbol. From the obscure pre-Caesarian figure known only for his “intemperance”, to the millionaire who made the table a field of total experimentation, to the man of Trajan’s time capable of sending fresh oysters to Parthia, “Apicius” came to signify less an individual than an idea: that of Roman gastronomic luxury — pushed to excess, theorised as an art, and transmitted in the form of a book.

[1] Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae, IV, 66:

Παρὰ δὲ Ῥωμαίοις μνημονεύεται, ὥς φησι Ποσειδώνιος ἐν τῇ ἐνάτῃ καὶ τεσσαρακοστῇ τῶν ἱστοριῶν, Ἀπίκιόν τινα ἐπὶ ἀσωτίᾳ πάντας ἀνθρώπους ὑπερηκοντικέναι.

Οὗτος δ’ ἐστὶν Ἀπίκιος ὁ καὶ τῆς φυγῆς αἴτιος γενόμενος Ῥουτιλίῳ τῷ τὴν Ῥωμαϊκὴν ἱστορίαν ἐκδεδωκότι τῇ Ἑλλήνων φωνῇ.

Περὶ δὲ Ἀπικίου τοῦ καὶ αὐτοῦ ἐπὶ ἀσωτίᾳ διαβοήτου ἐν τοῖς πρώτοις εἰρήκαμεν.“Among the Romans, it is reported, as Posidonius says in the forty-ninth book of his Histories, that a certain Apicius surpassed all other men in intemperance. This is the same Apicius who was the cause of the exile of Rutilius, author of a Roman History written in the Greek tongue. As for the other Apicius who also himself became famous for prodigality, we have spoken of him in the first book.”

[2] Tacitus, Annals, IV, 1: non sine rumore Apicio diviti et prodigo stuprum veno dedisse.

“…not without rumours that [Sejanus] had sold his favours to the rich and prodigal Apicius…”

This passage concerns Lucius Aelius Sejanus, praetorian prefect under Tiberius. The phrase associates the name of Marcus Gavius Apicius with the scandal of purchased sexual favours (stuprum) given “for money” (veno dedisse).

[3] Seneca, Consolatio ad Helviam, X, 9: cum sestertium millies in culinam coniecisset, cum tot congiaria principum et ingens Capitolii vectigal singulis comissationibus exsorpsisset, aere alieno oppressus, rationem impensarum suarum tunc primum coactus inspexit. Superfuturum sibi sestertium centies computavit et, velut in ultima fame victurus, si in sestertio centies vixisset, veneno vitam finivit.

[4] Seneca, Consolatio ad Helviam, X, 8: … quam Apicius nostra memoria vixit, qui in ea urbe, ex qua aliquando philosophi velut corruptores iuventutis abire iussi sunt, scientiam popinae professus disciplina sua saeculum infecit.

[5] Pliny the Elder, Natural History, X, 68 (133): Phoenicopteri linguam praecipui saporis esse Apicius docuit, nepotum omnium altissimus gurges.

See also VIII, 77 (209): Adhibetur et ars iecori feminarum sicut anserum, inventum M. Apici, fico arida saginatis ac satie necatis repente mulsi potu dato.

IX, 30 (66): M. Apicius, ad omne luxus ingenium natus, in sociorum garo — nam ea quoque res cognomen invenit — necari eos praecellens putavit atque e iecore eorum allecem excogitare.

[6] Pliny the Elder, Natural History, XIX, 41 (143): Nitrum in coquendo etiam viriditatem custodit, ut et Apiciana coctura, oleo ac sale, priusquam coquantur, maceratis.

[7] Pliny the Elder, Natural History, XIX, 41 (137): Hic est quidam ipsorum caulium delicatior teneriorque cauliculus, Apicii luxuriae et per eum Druso Caesari fastiditus, non sine castigatione Tiberi patris.

[8] Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae, I, 12 (7a-7b-7c): Ἐγένετο δὲ κατὰ τοὺς Τιβερίου χρόνους ἀνήρ τις Ἀπίκιος, πλουσιώτατος τρυφητής, ἀφ´ οὗ πλακούντων γένη πολλὰ Ἀπίκια ὀνομάζεται. Οὗτος ἱκανὰς μυριάδας καταναλώσας εἰς τὴν γαστέρα ἐν Μιντούρναις (πόλις δὲ Καμπανίας) διέτριβε τὰ πλεῖστα καρίδας ἐσθίων πολυτελεῖς, αἳ γίνονται αὐτόθι ὑπέρ γε τὰς ἐν Σμύρνῃ μέγισται καὶ τοὺς ἐν Ἀλεξανδρείᾳ ἀστακούς. Ἀκούσας 〈οὖν〉 καὶ κατὰ Λιβύην γίνεσθαι ὑπερμεγέθεις ἐξέπλευσεν οὐδ´ ἀναμείνας μίαν ἡμέραν. Καὶ πολλὰ κακοπαθήσας κατὰ τὸν πλοῦν ὡς πλησίον ἧκε τῶν τόπων πρὶν ἐξορμῆσαι τῆς νεὼς (πολλὴ δ´ ἐγεγόνει παρὰ Λίβυσι φήμη τῆς ἀφίξεως αὐτοῦ), προσπλεύσαντες ἁλιεῖς προσήνεγκαν αὐτῷ τὰς καλλίστας καρίδας. Ὃ δ´ ἰδὼν ἐπύθετο εἰ μείζους ἔχουσιν· εἰπόντων δὲ μὴ γίνεσθαι ὧν ἤνεγκαν, ὑπομνησθεὶς τῶν ἐν Μιντούρναις ἐκέλευσε τῷ κυβερνήτῃ τὴν αὐτὴν ὁδὸν ἐπὶ Ἰταλίαν ἀναπλεῖν μηδὲ προσπελάσαντι τῇ γῇ.

[9] Seneca, Letters to Lucilius, 95 (42): Mullum ingentis formae — quare autem non pondus adicio et aliquorum gulam inrito? quattuor pondo et selibram fuisse aiebant — Tiberius Caesar missum sibi cum in macellum deferri et venire iussisset, ‘amici,’ inquit ‘omnia me fallunt nisi istum mullum aut Apicius emerit aut P. Octavius’. Ultra spem illi coniectura processit: liciti sunt, vicit Octavius et ingentem consecutus est inter suos gloriam, cum quinque sestertiis emisset piscem quem Caesar vendiderat, ne Apicius quidem emerat.

[10] Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae, I, 13 (7d): Τραιανῷ δὲ τῷ αὐτοκράτορι ἐν Παρθίᾳ ὄντι καὶ τῆς θαλάσσης ἀπέχοντι ἡμερῶν παμπόλλων ὁδὸν Ἀπίκιος ὄστρεα νεαρὰ διεπέμψατο ὑπὸ σοφίας αὐτοῦ τεθησαυρισμένα·

[11] Tertullian, Apologeticus, III, 6: Quid novi, si aliqua disciplina de magistro cognomentum sectatoribus suis inducit? Nonne philosophi de auctoribus suis nuncupantur Platonici, Epicurei, Pythagorici? Etiam a locis conventiculorum et stationum suarum Stoici, Academici? Aeque medici ab Erasistrato et grammatici ab Aristarcho, coqui etiam ab Apicio?

The manuscript of the Vatican Apostolic Library can be viewed in its entirety online: Urb.lat.1146.