Translated from french (please notify us of errors)

It sometimes happens that an ancient book is less a work than an adventure: a long journey through culture, professional practice, kitchens and scriptoria. The De re coquinaria, transmitted under the name of Apicius, belongs to this category of texts that can only be grasped in motion. Behind the prestigious shadow of Marcus Gavius Apicius, celebrated gourmet of the 1st century, lies a collection whose material has been reworked, expanded, reduced, translated, reorganised over several centuries.

For a century, scholars have been attempting to order this ensemble. Jacques André, philologist and linguist specialising in technical Latin, editor of the text for Les Belles Lettres (1965), saw in the text the mark of a late compilation work, accomplished towards the end of the 4th century by a scholar familiar with dietetics. Others, such as Christopher Grocock, Latinist trained in textual criticism, and Sally Grainger, food historian and professional cook: in their critical edition (2006), invite us to beware of too neat a coherence. In their view, the collection is above all the heir to a living culinary tradition, closer to the daily practice of cooks than to literary constructions. These perspectives, far from being mutually exclusive, each illuminate a facet of this strange text, at once technical, composite and deeply rooted in its time.

An ancient core, but with no identifiable author

The collection undeniably contains a set of ancient recipes, perhaps contemporary with Marcus Gavius Apicius, perhaps merely originating from the culinary milieu that made his name a symbol of refinement. Attribution remains impossible to establish: the primitive recipes bear no author’s mark, and the Latin tradition itself used ‘Apicius’ as a culinary label long before the book took its current form.

The text shows gaps—recipe announced but absent[1], missing chapters in book VI[2], lost diagrams[3]—which bear witness to a troubled transmission. Nothing, however, allows us to conclude that the original collection was more structured than today: these absences may derive as much from copying accidents as from the progressive integration of notes and lists.

To this are added manifestly late additions, identifiable through recipes dedicated to illustrious figures, sometimes emperors or high-ranking magistrates[4]. Their chronology, often several decades or even several centuries after Apicius’s time, attests that the collection was supplemented over time. These dedications do not form a homogeneous layer: they seem to reflect the living use of the text by cooks.

Sauces, medicine, Greek grammar

Within this ancient core, several thematic ensembles intertwine.

Sauce recipes occupy an important place: Eduard Brandt, in 1927, devoted a detailed study to them and suggested that some derived from a De condituris attributed to Apicius by multiple late authors[5]. Book X, exclusively devoted to fish sauces, indeed seems to point to a different source from that of the dishes. But nothing compels us to imagine an autonomous treatise: the logic of a cook or scribe, progressively grouping similar recipes, may be sufficient to explain this configuration.

Alongside the sauces, the text reveals a recognisable medical layer: digestive remedies and laxative preparations[6], as well as a balneo recipes, that is, for dishes intended to be consumed immediately after bathing for therapeutic purposes[7]. André interpreted these passages as direct borrowing from a Latin dietetic treatise. One can equally well see in them the natural circulation of practices between medicine and cooking: in Antiquity, the learned cook is also a practitioner of health.

Still more ancient, or simply more identifiable, the Greek layer leaves a clear imprint: transliterated vocabulary (oxyzomum, leucozomus, embamma), Alexandrian techniques, syntactic constructions translated literally from Greek. Brandt distinguished two groups, that of the condita, recipes for flavoured drinks and spiced preparations[8], and that of the thermospodium (θερμοσπόδιον), warmer or bain-marie of Greek origin[9], deriving according to him from Hellenistic corpora. Nothing forbids this reading; but a bilingual culinary milieu sometimes suffices to produce this mixture of terminology and syntax, without it being necessary to suppose the existence of independent texts.

What appears clearly, however, is that the De re coquinaria does not arise from a literary project: it results from a long history of recorded gestures, taken up, translated, completed and reused.

Towards the end of Antiquity: a progressive formatting

The language of the collection, close to that of the Mulomedicina Chironis[10] and the Peregrinatio Etheriae[11], allows us to situate its final state towards the end of the 4th century. André imagined at this time a cultivated editor, perhaps a physician, bringing together several fascicles to make a culinary summa. This hypothesis has the advantage of coherence: it explains the presence of Greek titles, the division into ten books, the appearance of a thematic arrangement.

But it is equally possible—and this is the hypothesis of Grocock & Grainger—that this formatting was not the work of an individual: the recipes could have organised themselves progressively, from copy to copy, according to uses and practical groupings. The apparent unity would then be the effect of time, not of a project.

The manuscripts: a fragmentary inheritance

The material history of the text confirms this evolutionary character. No ancient manuscript has yet been unearthed. Around 820, the abbey of Fulda (in present-day Germany) must have possessed an archetype of which traces are found until the early 15th century, then it was lost.

From this model, however, derive two 9th-century Carolingian witnesses preserved to this day: one is in the Vatican library (Urb.lat.1146[12]) and the other at the Academy of Medicine in New York (Cheltenham/New York manuscript[13]). Their comparison reveals a text stable overall but fragile in its details, marked by the scribes’ hesitation before an often obscure culinary lexicon. Certain anomalies, which one might think ancient, are perhaps medieval rationalisations.

Vinidarius’s Excerpta

In late Antiquity circulated another collection of recipes attributed to Apicius, known under the name Excerpta Vinidarii. These Extracts from Apicius compiled by Vinidarius are preserved for us in a single manuscript, the Codex Salmasianus[14] (7th-early 8th century). The text first presents a list of spices, followed by thirty-one recipes. The language, manifestly later than the 4th century, led Brandt to date the compilation to the late 5th or 6th century. The compiler bears a name of Germanic origin, Vinidarius, sometimes connected to the Gothic Vinithaharjis, and it is possible that this collection was formatted in northern Italy.

Some recipes in the Excerpta take up preparations known from the De re Coquinaria[15], the majority are original. Should one deduce from this the existence of a more complete Apicius now lost? Or, as Grocock & Grainger think, a plurality of parallel traditions, with no fixed centre? Here again, the two readings are not mutually exclusive: one emphasises loss, the other diversity.

The imprint of a culinary world over several centuries

The De re coquinaria does not deliver to us the personal recipes of Apicius, but rather the imprint of a culinary world over several centuries. André’s analyses highlight a late organisation, a compositional effort that gives the collection a relative coherence. Those of Grocock & Grainger remind us of the shifting reality of technical traditions: a text shaped by practice as much as by copying, without author or architect, where each layer has been deposited on the previous one.

👉 Read also: The three Apicii, or how a name became synonymous with gastronomic luxury

Summary bibliography

- André, Jacques, Apicius. L’Art culinaire, Les Belles Lettres, Paris, 1965.

- Brandt, Eduard, Untersuchungen zum römischen Kochbuche, Leipzig, 1927.

- Grocock, Christopher & Grainger, Sally, Apicius. A Critical Edition with an Introduction and an English Translation, Prospect Books, Totnes, 2006.

- Giarratano, C. & Vollmer, F., Apicii sive De re coquinaria libri decem, Leipzig, Teubner, 1922.

References to the text follow the numbering of recipes established by J. André. They are supplemented by indication of the book, chapter and section.

[1] Apic. 4.3.2 (§166): Isicium Terentinum facies: inter isicia confectionem invenies. ‘Make the rissoles according to Terentius’s recipe—you will find it in the chapter on rissoles’. But the De re coquinaria contains no recipe for rissoles according to Terentius.

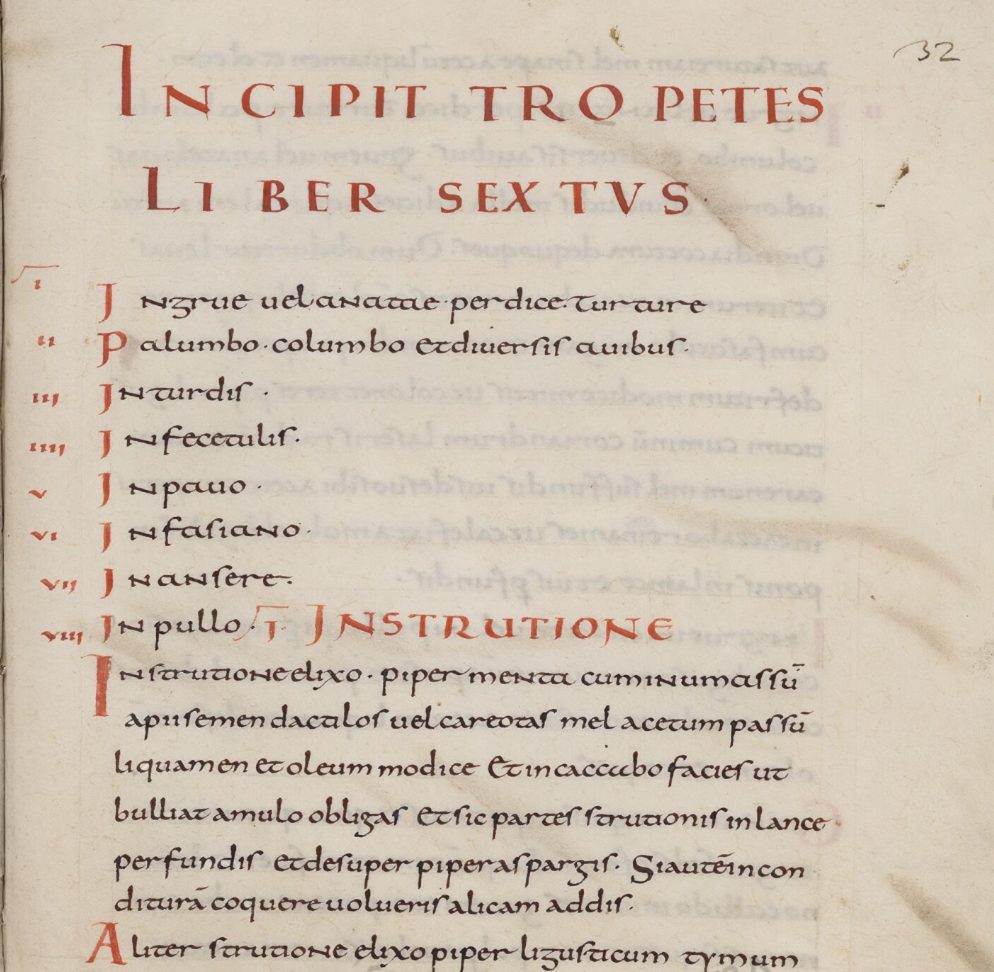

[2] Book VI has lost several chapters which are still mentioned in manuscript Urb.lat.1146 (see illustration). This concerns recipes for thrushes, peacocks, pheasants which are not found in the text.

[3] Recipe §141 (4.2.14) clearly refers to a lost illustration: patellam aeneam qualem debes habere infra ostenditur. ‘See below which bronze mould one must use’.

[4] See the table of figures cited in the recipes of the De re coquinaria.

[5] Several ancient and mediaeval authors attest to the existence of a work by Apicius on sauces and condiments: Tertullian mentions ‘Apician condiments’ (De anima 33: condimentis Apicianis); St Jerome evokes ‘the sauces of Apicius’ (Adversus Iovinianum 1,40: ad iura Apici); the second Vatican Mythographer specifies that ‘Apicius, a very voracious character, wrote much on condiments’ (II, 269 [= 225]: Apicius quidam voracissimus fuit, qui de condituris multa scripsit); a scholiast of Juvenal notes that ‘Apicius was the author of select banquets and wrote on little dishes’ (Schol. Iuv. 4,23: Apicius auctor praecipiendarum cenarum, qui scripsit de iuscellis); finally, a scholiast of the Querolus states that Apicius ‘invent[ed] the art of cooking and wrote much on condiments’ (Schol. Querolus p. 22,17: …qui primus coquinae usum invenit et de condituris multa scripsit).

[6] §29 (1.27.1: Spiced salt), §39 (1.34.1: Digestive oxigarum), §53 (2.2.5: Simple rissoles to loosen the bowels), §67 to §71 (3.2: Broth for the bowels), §108 (3.17.1: Nettles against illness), §111 (3.18.3: For digestion), §432 (9.10.12: This restores the stomach very well).

[7] §55 (2.2.7: recipe for starch rissoles to take on leaving the bath), §410 (9.4.3: boiled cuttlefish for leaving the bath) and §419 (9.8.5: another recipe).

[8] Recipes §1 (1.1.1: recipe for wonderful spiced wine), §2 (1.1.2: honeyed spiced wine…), §3 (1.1.3: recipe for Roman absinthe), §56 (2.2.8: another starch sauce), §58 (2.2.10: recipe for apothermum).

[9] Recipes §131 (4.2.4: runny patina), §135 (4.2.8: hot or cold elder patina), §136 (4.2.9: rose patina), §160 (4.2.33: hot and cold sorb patina), §417 (9.8.3: another recipe for sea urchin). Jacques André translates thermospodium as ’ember bell’.

[10] The Mulomedicina Chironis (literally ‘Chiron’s medicine for mules’) is a 4th-century medical treatise devoted to the treatment of horses.

[11] Peregrinatio Etheriae (or Itinerarium Egeriae) is the account, written in Latin around 381–384, of a pilgrimage to the Holy Land attributed to Egeria, a Hispano-Roman Christian.

[12] Urb.lat.1146 – DigiVatLib – Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana

[13] The New York Academy of Medicine’s Apicius Manuscript

[14] BnF, Paris, ms. lat. 10318 (Codex Salmasianus), notice codicologique et descriptive, Biblissima.

[15] Excerpta 2 = §131; Excerpta 4 = §266; Excerpta 8 = §434; Excerpta 13 = §154; Excerpta 18 = §435; Excerpta 19 = §155[9]. The titles have been modified: what was Runny patina (§131) became Runny caccabina (Excerpta 2).