Game of Five Lines

2 2 |

Race Race |

Chance Chance |

Easy Easy |

Medium Medium |

History

The Pente grammai (πέντε γραμμαί, ‘the five lines’) ranks amongst the oldest board games of ancient Greece, whose origins reach back far beyond what the earliest literary mentions suggest. The most ancient archaeological discoveries, unearthed at Anagyros in Attica, date to the 7th century BCE and bear witness to the antiquity of this ludic practice in the Greek world.

From temples to Exekias’s vases

The geographical spread of the game was considerable, as attested by the numerous boards discovered at different sites in ancient Greece. These boards, consisting of five parallel lines adorned with circles at the extremities, were sometimes carved directly into temple floors, suggesting a sacred or ritual dimension that transcended mere entertainment. This practice reveals the cultural importance accorded to the game in Greek society and its integration into religious spaces.

The first known literary mention dates back to Alcaeus of Mytilene, around 600 BCE. This lyric poet from Lesbos evokes the game in his works (fragment 351 Voigt), thus establishing its anchoring in archaic aristocratic culture and its symbolic value for the élites of the period. The game also finds an echo in Theocritus in his Idylls (6, 15-19), bearing witness to its persistence in Greek literature. These early references show that the Pente grammai was already sufficiently widespread and codified to be the subject of literary and metaphorical allusions.

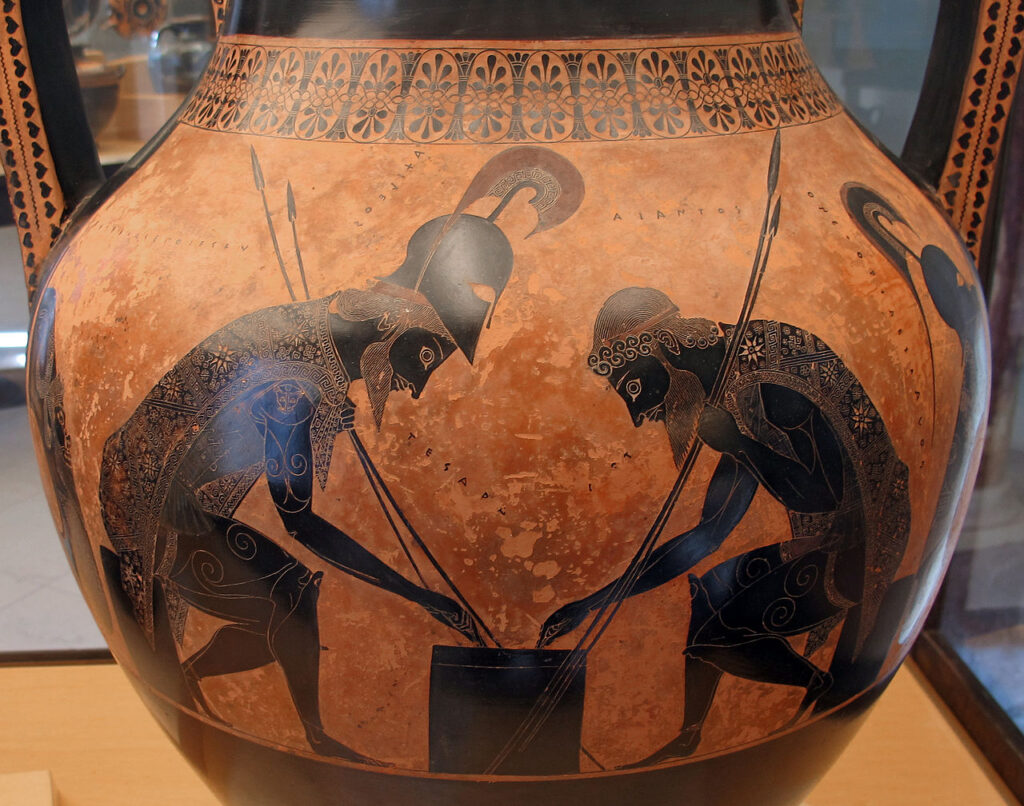

The iconography offers us a particularly rich testimony with the numerous representations on Attic vases dated to around 500 BCE. More than 160 preserved specimens show the heroes Ajax and Achilles absorbed in a game during the siege of Troy. The most celebrated of these works, attributed to the painter Exekias around 540-530 BCE and preserved in the Vatican, perfectly illustrates the association between the game and the heroic values of the warrior aristocracy. This recurrent iconography demonstrates that the Pente grammai was perceived as an attribute worthy of the greatest heroes, revealing its symbolic dimension in the construction of the Greek aristocratic ideal.

When moving a piece became proverbial

The most complete and systematic description comes to us from the grammarian Julius Pollux in the 2nd century CE, in his Onomasticon. Pollux writes precisely: ‘on the five lines from either side there was a middle one called the sacred line. And moving a piece already arrived there gave rise to the proverb “he moves the piece from the sacred line”.’ It is revealing that Pollux does not explicitly name the game, merely describing it as a historical element, which suggests that in his time, the practice had already disappeared from contemporary usage.

The terminology used by Pollux, notably the designation of ‘sacred line’ (ἱερὰ γραμμή) for the central position, reveals the ritual or symbolic importance accorded to this strategic placement. This sacralisation of the game space inscribes itself in a broader Greek conception where ludic activities participate in a cosmic and religious order, transcending the simple recreational dimension.

The proverbial expression drawn from the game enjoyed good fortune in ancient Greek literature. Moving a piece from the sacred line had become metaphorical for a bold and risky decision, since having all one’s pieces on this central line normally constituted the game’s objective. According to the modern analysis of Stephen Kidd, this movement represented a rare and aggressive strategy, which explains why the expression endured well beyond the disappearance of the game itself to designate any act involving a calculated sacrifice with a view to a superior advantage.

The game mechanisms, as they can be reconstructed from available sources, involved two players each moving five pieces on the board, probably anticlockwise. Victory would likely have gone to the first player succeeding in gathering all his pieces on the sacred line. The game was played with one or two dice, although the exact modalities of advancement remain uncertain. The number of lines was not necessarily limited to five, and variants containing more lines were probably accompanied by a proportional number of pieces per player. In the Roman period, the board arrangement evolved to consist of two rows of five squares, reflecting an adaptation of the game to the tastes and ludic practices of this period.

In the absence of complete rules transmitted by ancient sources, several scholarly reconstructions have been developed, notably by Ulrich Schädler and Stephen Kidd. These works are based on the ensemble of available testimonies, from the mentions of Alcaeus and Theocritus to the late commentaries of Eustathius Macrembolites on the Odyssey in the 12th century (1396, 61; 1397, 28), passing through the comparative analysis of other ancient board games presenting similar structures.

The version reconstructed here, centred on the objective of uniting one’s pawns on the sacred line, thus represents the most coherent synthesis of the historical and archaeological data at our disposal.

Set-up

5 pieces per person / 1 dice

The game board consists of five parallel lines. The middle one is called the ‘sacred line’ and is divided in two by a circle.

The protagonists’ pieces are situated outside the game board. They will enter by the right extremity of line A for one, by the left extremity of line B for the other. The circles at the end of the lines are the squares where the pieces are placed. These turn in the direction indicated on the diagram by the blue arrows.

Object of the game

Each protagonist must bring his five pieces onto the game board, then succeed in placing them on the part of the ‘sacred line’ situated on his opponent’s side. The first person to achieve this has won.

Course of play

The protagonists draw lots to see who begins.

The player whose turn it is throws the dice, then advances a piece by the corresponding number of squares whilst respecting the following rules:

- each square (circle) can contain only one piece;

- pieces can jump over occupied squares;

- the introduction of pieces onto the board takes priority over the advancement of pieces already engaged. If the value of the dice does not permit bringing a new piece onto the board, another piece must be moved;

- when a movement is possible, the player is obliged to carry it out;

- if no movement is possible, the player passes his turn.

- When a piece can move to a square occupied by an opponent’s piece, this piece is ‘taken’ and removed from the game. The player concerned must reintroduce it as a priority. Only pieces placed on the ‘sacred line’ are safe from capture.

Pieces that arrive on the square at the end of the ‘sacred line’ can be ‘sanctified’ upon it.

Variant

A variant –which lengthens the playing time– can be introduced:

- If no movement is possible, a player must bring out a piece from the ‘sacred line’ to put it back into circulation on the board (starting from the entry square and in the same direction as the other pieces).

More

- Play Pente grammai online, on the Locus Ludi website, a European research project.

Return to the home page on ancient board games (in french)